The Edison studio reenacts an 1894 news sensation about a homeless man who entered the Astor mansion and fell asleep in one of the servant’s beds. What seems like a quirky tale is really a story of cruelty and inequality in the Gilded Age.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress

Snatching Some Zzzzzs

Singing along with projected images had been a popular feature of the magic lantern days, so it was an obvious addition to the motion picture repertoire and the Edison company was determined to popularize music synchronized to the screen, either via recordings or specially arranged sheet music played live.

Edison was not the only company seeking to synchronize movies and sound but they tied with Gaumont for being the most committed to the commercial technology in the long term. Edison introduced the Kinetophone in 1894, a peepshow machine synchronized to a recording that the listener enjoyed via communal earpieces attached to stethoscope tubing. This technology was quickly overshadowed by the wild popularity of projected cinema that kicked off in 1895, catching Thomas Edison with his pants down and forcing him to buy projecting technology. (Still claiming it as his personal invention, of course.) Edison later reused the Kinetophone brand name for a series of true singing and talking pictures in 1913 (I cover this failed attempt in my reviews of Jack’s Joke and Nursery Favorites).

Between these two Kinetophone attempts, the Edison catalog reveals further attempts to bring words to the movies, focusing on Picture Songs. Per the 1900 catalog: “We have at last succeeded in perfectly synchronizing music and moving pictures. The following scenes are very carefully chosen to fit the words and the songs, which have been especially composed for these pictures.” I have not seen the sheet music that originally went with the Picture Songs but it was likely synchronized to onscreen cues.

The Astor Tramp (1899, director: James H. White) was one of these Picture Songs. “A side-splitting subject, showing the mistaken tramp’s arrival at the Wm. Waldorf Astor mansion and being discovered comfortably asleep in bed. by the lady of the house. Length 100 feet, complete with words of song and music, $20.00. Without music, $15.00.” (That’s nearly $800 for film and music, keeping in mind that films were sold outright, not leased, and the entire runtime was a bit over two minutes.)

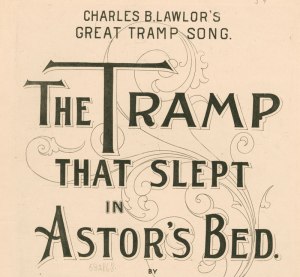

The music was likely The Tramp That Slept in Astor’s Bed (1894) by Charles B. Lowler and James W. Blake. In the film, the tramp finds his way into a bedroom and rejoices at his good fortune. He tries on some of the powders and perfumes in the vanity and then settles into the soft bed for a snooze. The lady of the house returns and does not notice him at first. When she realizes that the bed is occupied by an interloper, she flees. A maid comes to investigate and likewise runs away in terror. Finally, a policeman arrives to take the tramp away. The tramp is later shown reading about his own exploits in the newspaper and congratulating himself, kicking away the small paperboy who asks for payment.

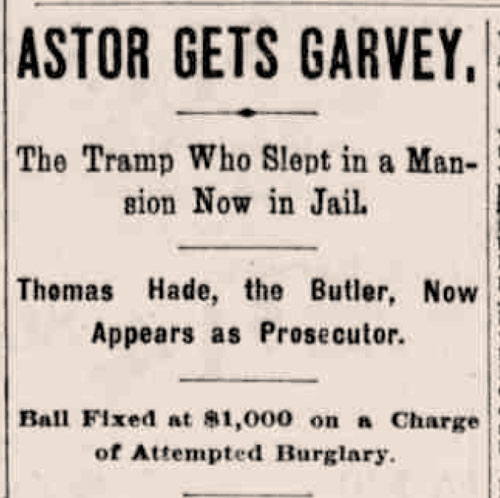

The song was based on a true 1894 event. At the time, the Astors were one of the richest families in America and the idea that someone as low as a tramp could just wander in and help himself to a cozy bed was amusing in itself but this was also a tale of income inequality, vindictive prosecution and the entitled cruelty of one of the richest humans to ever live. The story dominated newspaper front pages before morphing into the quirky Tin Pan Alley retelling and, finally, being forgotten altogether.

On November 17, 1894, John Garvey, a self-described Irish immigrant in his early thirties, slipped through an open door and into the Astor family’s Fifth Avenue mansion. Once inside, he followed a staircase, which led to the empty bed of a staff member. Garvey locked the door, undressed and fell asleep. He slept so soundly, in fact, that his loud snores alerted the household to his presence hours later. Garvey was arrested without a struggle.

Garvey claimed he entered the house because some workers told him to get a bed at the Astors. This was probably a sarcastic joke given the family’s famous hotel business but Garvey seems to have taken it literally. He had not stolen anything, nor had he made any attempt to harm anyone in the house and there was no evidence that he had tried to enter any rooms beyond the servant’s bedroom. He had undressed to go to bed, true, but had locked the door behind him. In short, there was nothing to indicate that he had intended anything more than what he had described and what the police found: a man in dire circumstances stumbling into a comfortable bed on a cold November night in New York City with temperatures hovering around freezing.

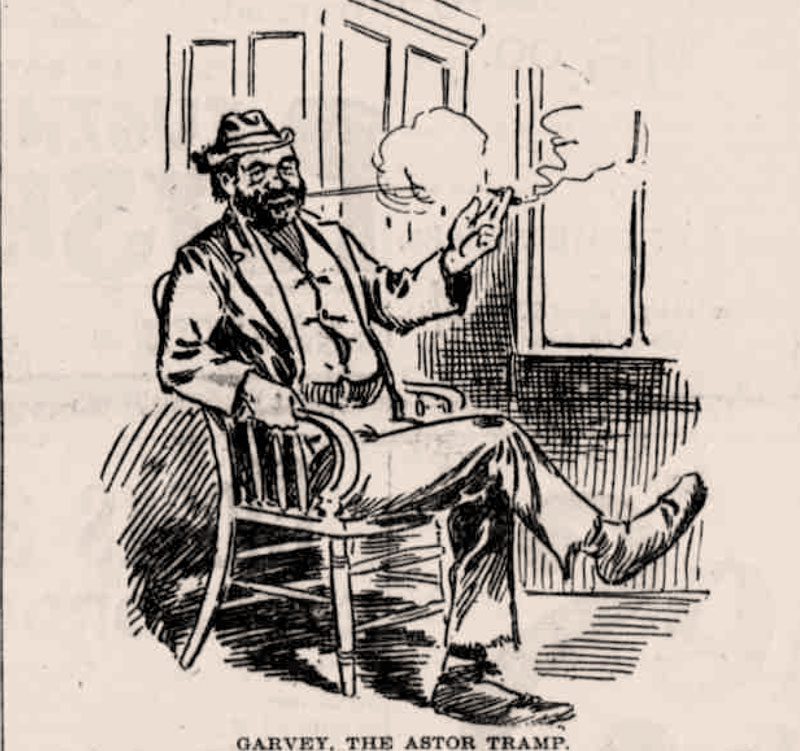

New York World star reporter Nellie Bly arranged an interview with Garvey. Reports following the incident had described him as a “tomato-can tramp” and “sodden.” (In his 1899 book on the homeless, Josiah Flynt defines a tomato-can tramp as “the outcast of Hoboland a tramp of the lowest order who drains the dregs of a beer barrel into an empty tomato can and drinks them he generally lives on the refuse that he finds in scavenger barrels.”)

Bly stated that Garvey showed no physical symptoms of alcoholism, and was polite and soft-spoken. He did not have the hands of a laborer and his clothes were of uncommonly good quality for a man in his position. He claimed to have been from the North of Ireland, where he had been a bartender, and had been in America for six years. After some hesitation, he responded in the affirmative when asked if he was Catholic. Bly remarked that his accent sounded English and he affected a brogue for a bit before dropping it. (I am not sure if this was because Americans often lack an ear for the nuances of different Irish and English accents, or if Garvey was a secret Englishman.)

Bly pressed for details and Garvey deflected, claiming to not know the status of his family back in Ireland or to have any friends in New York she could contact.

“Would you tell a lie?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said, promptly and frankly.

“Then you’d better go to confession at once,” I added.

“It’s no harm to lie,” he asserted, calmly, still smiling, and that is the only voluntary remark he made during the interview.

“Is it surprising that John Jacob Astor wants to know something about the Astor tramp?” Bly concluded at the end of her article.

Or, as the Tin Pan Alley song put it, “I am the trap that slept in Astor’s bed you see; all the papers had an interview with me; but even Nellie Bly who is reckoned pretty fly; she could get nothing out of yours truly.” This rakish attitude, which the real Garvey did not display, can be seen in the illustration of Garvey that accompanied articles published in the New York World.

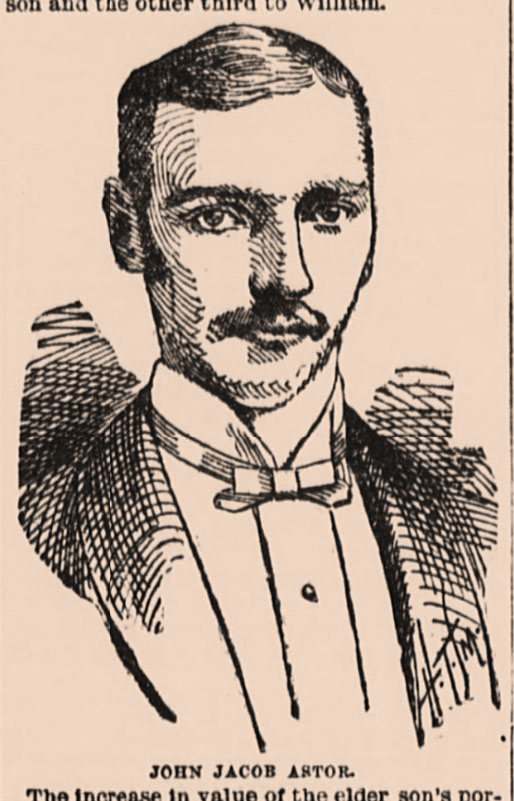

John Jacob Astor IV’s modern reputation mostly rests on his refusal to enter lifeboats before women and children and perishing on the Titanic but at the time, he was the spoiled young heir of a massive fortune, New York’s landlord, a big C Conservative, a great believer in bootstrapping and he was hopping mad. The law of New York City had seen fit to deal with Garvey sans any Astor input and had fined him the sum of $5, which had quickly been paid for him by an anonymous supporter.

Astor demanded that Garvey be charged with burglary despite the fact that nothing had been taken from the home or found on Garvey’s (naked as a jaybird) person. There was speculation that Garvey had been looking for papers of some kind or another and had dropped them to a confederate below before being discovered in the house but he had entered at 6:00 p.m. and was discovered four hours later at 10:00. Stripping down and pretending to be asleep, snoring so loudly that he alerted the household, seems like a rather strange strategy.

Astor would not be denied. “I am utterly at a loss to understand why anyone would want to pay the fellow’s fine and let him get away,” he declared, and continued to rant about the great injustice that had been done to him. At his insistence, New York officials charged Garvey with burglary and sought a year in jail, setting his bail at the outrageous sum of $1,000 (almost $37,000 today).

This response was out of all proportion, especially considering the relative social classes of the two men. However, nobody insists on the laziness and perfidy of the poor like the heir to generational wealth and Astor was true to his roots. Both the press and the general public considered him to be a brat and a bully, picking on a man who had done no real harm and was so clearly battered by life, especially egregious in the aftermath of the Panic of 1893 and subsequent economic depression. The response ranged from sarcastic to outraged:

“J.J. Astor never had a tramp on his hands before and he is going to make the most out of this one.” –New York Journal

“It is a big crime in the eyes of John Jacob Astor for a tramp to sleep in one of those downy Astorian beds.” –Yonkers Statesman

“Somebody ought to tell Jack Astor what a silly mess he is making. He evidently has not with enough to see it himself.” –Rochester Times

“The penalty for trespassing in the Astor mansion should be just the same as the penalty for trespassing the rooms of the poorest tenant of a house or rooms.” Pittsburgh Dispatch

“Jack Astor has run down Garvin [sic], the tramp. Mr. Astor seems to think that law for millionaires is different from that framed for ordinary individuals.” Philadelphia North American

Garvey’s meals were paid for by sympathetic supporters and he was evidently comfortable in jail, though he remained as passive and sleepy as ever. The study of mental health was quite primitive in the 1890s but a follow-up story in the New York World describes Garvey as sleeping almost constantly, only showing interest in a Christmas turkey feast and asking if he was permitted to eat all he wanted. Armchair diagnosing is risky but, 130 years on, it’s all we have and it’s possible Garvey was suffering from depression.

Garvey’s cases wended through the courts and he was finally declared insane on May 15,1895 and committed to Matteawan State Hospital. By this time, the story had slipped out of the public eye and the news was relegated to page 5 of the New York World. This was likely the most convenient conclusion for the Astor family and the New York justice system, as insanity removed the question of favoritism for the wealthy. Garvey was released sometime after and an 1896 item in the Savannah Morning News boasted that he was once again a tramp.

Garvey died in June of 1897. In its death announcement, the New York Journal claimed that after Garvey had been released, he had taken a job as a “freak in a dime museum,” a longshoreman and, finally, committed another petty crime and was then returned to Matteawan. The National Tribune of Washington D.C. crowed: “The Astor tramp is dead. He died in an insane asylum, the prominence he attained by sleeping in an Astor bed having unbalanced his mind. His fate should be warning to all tramps who are tempted to come in contact with clean sheets.”

The real Garvey is a sad case, likely exacerbated by the poor understanding of mental health at the time and certainly by the bullying of Astor, but the Garvey who lived on in song and film was the one pictured in the World caricature: a jaunty and mischievous fellow who dared to help himself to the fat of a rich man’s table. He may have paid the price but what a way to go.

The fact that the Edison company selected The Astor Tramp for its sound film collection nearly five years after the original incident and two years after Garvey’s death is a testament to the “print the legend” nature of his brief legacy. In 1928, the trade magazine Exhibitor’s Herald-Moving Picture World printed a brief story about exhibition at the dawn of cinema and The Astor Tramp was the film their veteran interviewee remembered by name.

The reality of a mentally and physically exhausted homeless immigrant stumbling into the comparatively luxurious unoccupied bed of a servant doesn’t make for a rousing tune, so the tramp joyously celebrates in the very bedroom of the Astor family proper, trying perfume and enjoying both the lark and the notoriety it brings him.

We know little of John Garvey’s final years, while John Jacob Astor is lovingly memorialized, his sins and certainly the memory of his malice toward Garvey washed away in the saltwater of Titanic glamour. Even in death, the law for millionaires is different from that framed for ordinary individuals.

Where can I see it?

Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Wow, what a sad story. Thank you for your thorough research and excellent writing!

Thank you! Glad you enjoyed!