When the lady of the house wants to keep things light by serving a salad without dressing, their cook serves the salad… without dressing! A mildly naughty pun became tied up with anti-immigration sentiment in this nineteenth century comedy.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD and Bluray.

You just can’t find good help these days!

The American Mutoscope and Biograph Company was brand new when it produced this short comedy based on a popular gag of the day: miscommunication between the master or mistress of the house and their servants.

In this case, a couple is sitting down to dinner when the wife goes to remind the cook that the salad is to be served undressed. The Irish cook gestures “What will these crazy Americans want next?” and removes her clothing down to her corset and chemise. The wife is horrified and the husband amused when they receive, as requested, their salad to be served undressed.

As was often the case in comedies of this era, the joke can be found both on the screen and on humorous picture postcards, which likely pre-dated the movie version. (In The Emergence of Cinema: The American Screen to 1907, Charles Musser states that a joke photograph definitively pre-dates the film.) American and British postcards of the era frequently portrayed Bridget—and it was always “Bridget” even if the undressed food varied between salad, potatoes and tomatoes—dressed only in a chemise and declaring some versions of “I’ll not take off another stitch even if I lose my place!”

Despite the film being described as censorable and erotic by some modern writers, it showed less skin than the postcards that were legally allowed to pass through the postal systems of the United States and Great Britain and was likely seen as mildly naughty, if that. As shown by The Kiss and Fatima’s Coochee-Coochee Dance, modern people tend to view Gilded Age moviegoers as stereotypical Victorians fainting at the sight of piano legs, which simply was not the case. And it’s ironic, given how much of How Bridget Served the Salad Undressed relied on vintage stereotypes of a different sort.

Now, the object of the film would have been to laugh at Bridget—an Irish immigrant in America at a time when xenophobia was aimed in that direction— rather than with her. However, if you wished to put a revisionist spin on the gag, it could be thought of as what we now call malicious compliance: following instructions literally and to the letter in the most destructive way possible. I, for one, welcome the idea of a malevolent Amelia Bedelia. However, we cannot review the movie we wish was made and that means we need to address the trope of Bridget and how Irish people were portrayed in early American cinema.

Just as the name “Karen” has recently become shorthand for “demanding and unreasonable woman,” Bridget carried considerable baggage for young Irish women looking for employment in the 19th and early 20th centuries. “Bridget” was typed as a coarse, temperamental, ignorant and frequently lascivious sort. She would sow chaos in the home, both intentionally and by accident. “No Irish need apply” was a refrain in advertisements but, due to a shortage of domestic labor, employers could not always afford to indulge their prejudice. In at least one case, a young Irish woman was obliged to change her name in order to be taken seriously.

The “Bridget” was a common figure in American films of the early silent era. In The Suburbanite (1904), a family of New Yorkers try to relocate to the quiet of the New Jersey suburbs but the last straw in their misadventure comes in the form of a violent cook/housekeeper, who assaults the family and ends up arrested. The central conflict of A House Divided (1913) is resolved when a separated couple believe that their Irish maid’s boyfriend, whom she has slipped into the house for some hanky-panky, is a burglar. Bridget was also prone to blow herself up in the fireplace. Dozens upon dozens of comedies following the antics of Bridget were released in the 1890s and 1900s but things began to change in the 1910s.

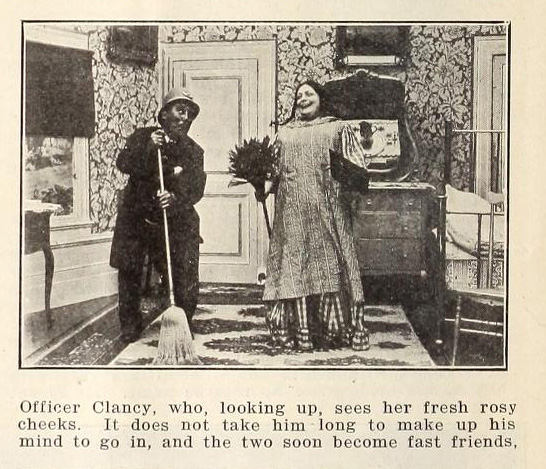

The shift in the status of Irish-Americans as their status as “other” fell away can be seen in another stereotypical name: Clancy. Officer Clancy, to be precise, because he was almost always a policeman. Three films released within weeks of one another in 1910 showed the range of characterizations associated with the name, as contrasted with the treatment of Bridget.

In Maggie Hoolihan Gets a Job, Clancy is a walking stereotype who marries the title character and has “only” ten children with her. In Mike the Housemaid, Officer Clancy is a bit of a rascal but manages to catch some burglars when he was actually trying to avoid duty. In the film simply titled Clancy, he is a true-blue policeman who just wants to get home for Christmas with his loved ones and dies gallantly in the line of duty. Bridget never received the same level of regeneration but Irish stereotypes were either fading or reframed as “affectionate.” By the late 1910s, Irish-Americans enjoyed enough institutional power to successfully protest and censor xenophobic humor in the Paramount picture Castles for Two.

(This was not the experience of every ethnic group, nationality and race subjected to prejudiced humor in early film. Who was allowed to complain about damaging cinematic portrayals, whose complaints were listened to, and who was able to effect actual change varied greatly, so these matters must be examined in context.)

Bridgets became less ubiquitous in American comedy, though they did not disappear entirely, and the “salad undressed” wordplay became divorced from its ethnic humor origins. Stan Laurel, who loved to skillfully repurpose and reimagine vintage gags in his popular comedies with Oliver Hardy, is probably the most recognized undressed salad server, doing so in male underwear in Soup to Nuts from 1928 (with a tracking shot focusing on his backside, yet!) and again in drag in A Chump at Oxford (1940). President Franklin Delano Roosevelt apparently had his staff in stitches when he proposed such an activity.

I was curious to know whether the “salad, undressed” wordplay would work in the Irish language, so I asked Darach Ó Séaghdha, author of the glorious Motherfoclóir: Dispatches from a Not So Dead Language, if this was possible and he was kind enough to answer. Saucing or dressing food vs the state and quantity of a person’s attire is a totally different adjective in Irish, so the answer is no, Bridget would never have had such a misunderstanding in Irish. (Not that I expected nineteenth century joke writers to research such a thing or care if they did know.)

Bridget sowed chaos in trying to keep up with the bizarre whims of her American employers (“if they want the salad undressed, they’ll get it undressed”) but she was also a survivor. Performers of Irish descent soon made up a large portion of the Hollywood star system in the silent and classic film periods, from Mary Pickford to James Cagney to Maureen O’Hara. Bridget has retired in American films but the lessons of the era—that new immigrant groups are frequently the targets xenophobic humor—sadly remain relevant today.

Where can I see it?

Released as part of the Cinema’s First Nasty Women collection with a score by Naomi Geena Nakanishi. The print is from the Library of Congress and appears to be from their paper print collection. These were films preserved on photo paper for copyright purposes, which resulted in a loss of image quality but also accidentally saved many pictures that would otherwise have been lost.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.