One of the most iconic images in early film is seeing a man with an enormous mustache kiss the woman he loves in closeup. Hailed as the first cinematic kiss, this film was certainly one of the earliest smash hits of American cinema.

Peck, smooch, smack, snog, tonsil hockey, play post office…

The Kiss was one of the biggest hits of early projected cinema and is probably the most iconic image of 1890s motion pictures. A mustachioed man happily embraces and kisses the woman he adores in closeup. Ah, true love! It all lasts less than a minute.

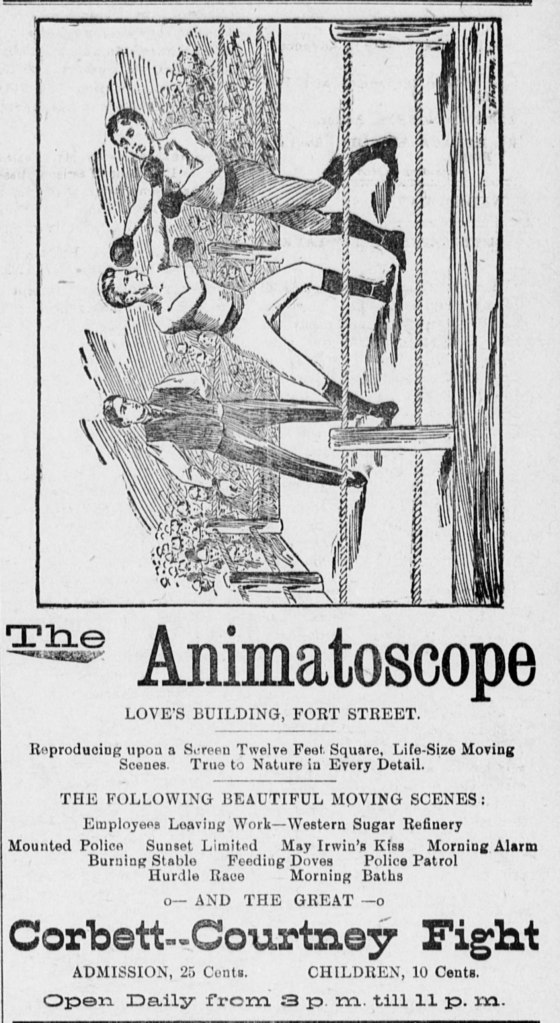

Prior to 1895, peepshows had been the favored way to watch the movies but projected cinema was the wave of the future. Not everyone was happy with this development. (Peepshows didn’t disappear entirely and are still fixtures at carnivals and amusement parks to this day but they did cease to be the predominant way to watch movies.)

The pioneering Edison company always had a software vs. hardware problem; they wanted to sell the means of playing movies and weren’t so concerned about providing content for those machines. The Edison Kinetoscope parlors had essentially throttled the need for a large motion picture catalog as movies could only be screened to one customer at a time. From Edison’s point of view, it made no sense to trade in a room full of Kinetoscopes for just one theater projector. In addition to killing equipment sales, projected cinema meant that hundreds of people could see a movie at once and they were clamoring for more variety.

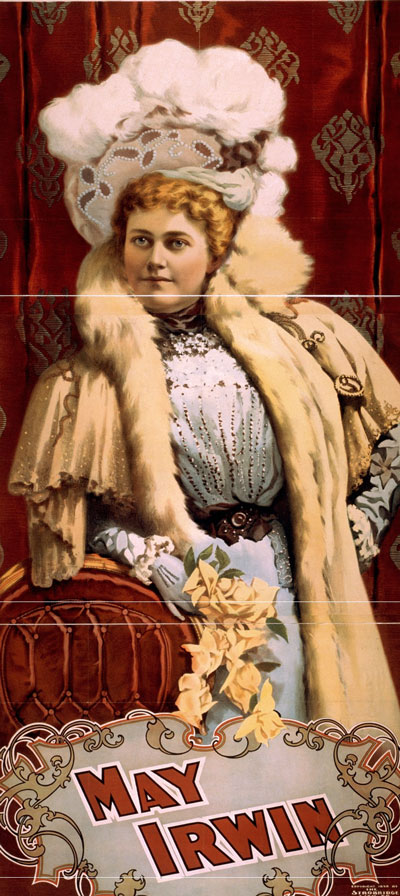

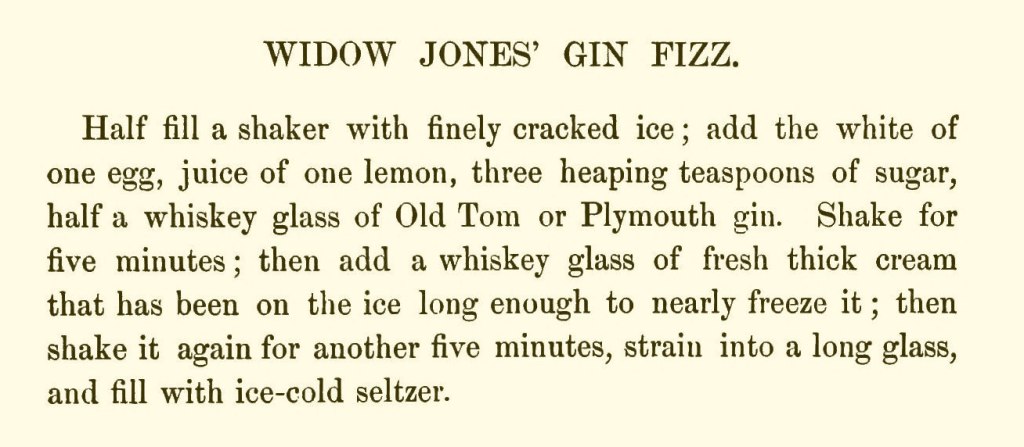

Edison was caught off-guard by the projection craze, it had a rather limited catalog and its famous Black Maria studio (essentially a glorified potting shed) was already obsolete. However, the company did manage to sign stage stars May Irwin and John C. Rice to reenact the kiss from The Widow Jones. (Given the timing of the film’s debut was so close to the unveiling of the Edison Vitascope projector, it is likely the film was made with Kinetoscope peepshows in mind.) The Widow Jones was a new play that would become Irwin’s big hit and one of the musical numbers, Bully Song, would become her theme.

(Content Disclosure: The song contains the repeated use of racial slurs and other sheet music releases of the song feature far more racist imagery. You can hear a 1907 NSFW recording of the song courtesy of the Library of Congress. You can read more about Irwin’s controversial career in May Irwin: Singing, Shouting, and the Shadow of Minstrelsy by Sharon Ammen)

I think we can all agree that The Kiss benefits from silence, if the lyrics are any indication of the play’s content. Rice and Irwin speak their dialogue as though they were on stage and then Rice smooths his mustache and leans in for a nuzzle. (Dialogue cards were not yet a thing, by the way.) What it lacks in plot, it makes up for in quirky charm and while they are certainly acting, Rice and Irwin do not mug for the camera.

So, that’s it. Review over, right? Well, not exactly.

Two questions arise when discussing The Kiss. First, was this actually considered sexy in 1896? And, second, did it cause a scandal? So, let’s dive in.

Given the somewhat goofy demeanor of Rice in particular, modern viewers naturally wonder if this, this, was what Gilded Age Americans considered desirable.

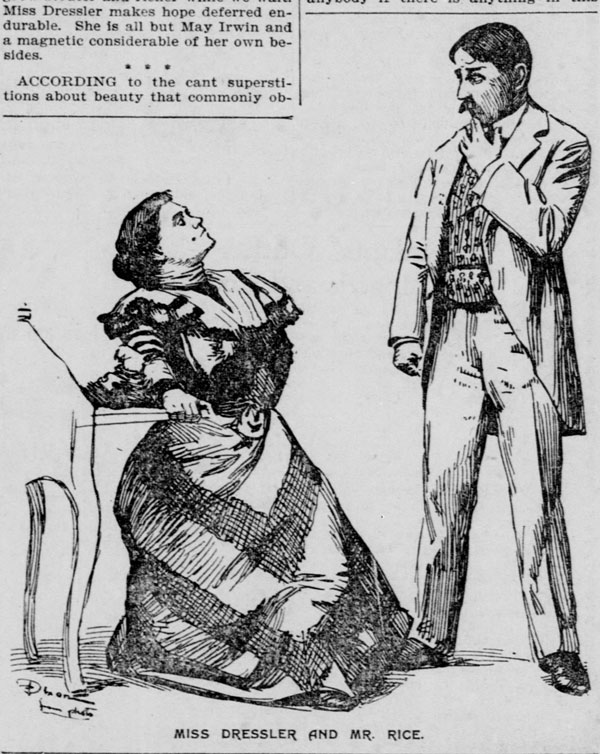

Not really. The Widow Jones was a comedy about a woman who poses as a widow for social reasons and the chaos that ensues before the final clutch. May Irwin’s stage persona can be compared to Marie Dressler. (In fact, Dressler succeeded Irwin as Rice’s costar.) She was not a star due to her Gibson Girl looks but rather because of her talents as a funnywoman. So, it certainly was not intended to be particularly sexy, though a slight naughty wink would have been in keeping with the tastes of the time. Speaking of naughty…

Let’s examine the second question: was there a scandal? If there’s one fact everyone knows about the May Irwin Kiss, it’s that it caused a scandal when it was first released. People kissing in closeup on the screen? Lips touching? Oh my, we shall surely die!

When I decided to review this film, I wanted to include some of those condemnations from primary sources but the funniest thing happened. The only condemnation that is quoted is a piece from a short-lived literary magazine called The Chap-Book, which was edited by Herbert Stuart Stone. (By the way, Stone died on the Lusitania in 1915. The poor man couldn’t seem to avoid being part of history.)

From the out-of-context quotes, it certainly sounds like Stone had a bee in his bonnet. While some books on sex and censorship in the movies do reprint the entire item, most take a few choice sentences that are particularly piquant.

“Magnified to Gargantuan proportions and repeated three times over it is absolutely disgusting. All delicacy or remnant of charm seems gone from Miss Irwin, and the performance comes very near being indecent in its emphasized vulgarity. Such things call for police interference.”

Yikes! Sounds like someone is caught in a tizzy and pearls are rolling on the floor from all the clutching. But The Chap-Book was aimed at the intelligentsia, it was not a religious magazine nor dedicated to reform. I think we need to look at context and see if the author was really so very offended. So, here is the complete 1896 item discussing The Kiss:

“One’s acerbities of temper are not pleasant things to emphasize, and geniality and indulgence are tempting. But the ever-recurring outrages to decency and good taste which I see in books and on the stage force me constantly into the role of Jack the Giant-killer; in common phrase: “I have my hammer out most of the time.”

Now I want to smash The Vitascope. The name of the thing is in itself a horror, but that may pass. Its manifestations are worse. The Vitascope be it known, is a sort of magic lantern which reproduces movement. Whole scenes are enacted on its screen. La Loie dances, elevated trains come and go, and the thing is mechanically ingenious, and a pretty toy for that great child, the public. Its managers were not satisfied with this, however, and they bravely set out to eclipse in vulgarity all previous theatrical attempts.

In a recent play called The Widow Jones you may remember a famous kiss which Miss May Irwin bestowed on a certain John C. Rice, and vice versa. Neither participant is physically attractive, and the spectacle of their prolonged pasturing on each other’s lips was hard to bear. When only life-size it was pronouncedly beastly. But that was nothing to the present sight. Magnified to Gargantuan proportions and repeated three times over it is absolutely disgusting. All delicacy or remnant of charm seems gone from Miss Irwin, and the performance comes very near being indecent in its emphasized vulgarity.

Such things call for police interference. Our cities from time to time have spasms of morality, when they arrest people for displaying lithographs of ballet-girls; yet they permit night after night a performance which is infinitely more degrading. The immorality of living pictures and bronze statues is nothing to this. The Irwin kiss is no more than a lyric of the Stock Yards. While we tolerate such things, what avails all the talk of American Puritanism and of the filthiness of imported English and French stage shows?”

First, note that the primary objection to The Kiss is the lack of physical attractiveness. Stone is not complaining about the act of kissing, he is complaining about kissing between people he finds to be unattractive. (The Chap-Book is full of stories and poetry with plenty of smooching.)

Second, Stone’s call for police interference is almost certainly as hyperbolic as his proclamation that he wanted smash the Vitascope machine. His primary complaint was that imported stage shows and fine art were being censored while May Irwin and John C. Rice were allowed to neck with abandon simply because their romantic scene was captured on the newfangled fad gadget.

Third, Stone clearly objected to the Vitascope in general and considered it to be low entertainment fit only for the unwashed masses. This attitude became commonplace after the initial excitement of projected films wore off.

Further, even if Stone was in deadly earnest about wanting law enforcement to shut down Edison motion picture shows, this was one editor’s note in one small magazine. Books that quote Stone confidently assert that there were numerous cries for censorship (some even laying blame for the anti-Kiss movement on the Vatican itself) but citations are a bit thin on the ground.

So, basically, my research went like this:

Book: The Kiss was condemned as obscene by all and sundry!

Me: Let me read those condemnations.

Book: Well, The Chap-Book says…

Me: But is there anything else?

Book: Lots of people condemned it.

Me: Like who?

Book: Well, The Chap-Book says…

Me: Yes, but any other sources? I need more than one, you know.

Book: …

Me: Because you do get that this was a sarcastic condemnation, right? The author just wanted to make a point about girlie shows being shut down and nude statues being denounced.

Book: …

Me: So, please show me another source.

Book: Well, The Chap-Book says…

So, I decided to take a look at Million and One Nights: A History of the Motion Picture Through 1925 by Terry Ramsaye. This 1926 book is wildly inaccurate in many places but it gives a good overview of the popular views of early film held while the silent era was still a going concern.

Ramsaye states that The Kiss did indeed cause a scandal and his evidence is… The Chap-Book. Sigh.

What about claims of condemnation from the clergy? Well, I haven’t found much on that score either. In fact, in his excellent book, The Emergence of Cinema, Charles Musser points out that The Kiss was part of at least one church-sponsored picture show fundraiser and that serious opposition to movies during this early period seldom arose within the congregations, save for a few older and highly conservative members. Musser concludes that the money raised by picture shows was just too good to resist. (Though, obviously, religious groups quickly changed their tune regarding morals in the movies.)

Incidentally, Musser points out that during 1896, projected cinema was still enough of a novelty to protect it from the rancor of reformers but all bets were off after that. In 1897, Reverend Frederick Bruce Russell personally raided Coney Island with the goal of stopping lascivious Mutoscope shows. The films targeted for ban included What the Girls Did with Willie’s Hat and Fun in a Boarding House.

(Russell later found himself in trouble with the law and was charged with extortion in 1901, eventually skipping town in 1902 and forfeiting the $2,000 bond his father had posted. Cough, cough, Matthew 7:5. After Russell jumped bond, The Christian Advocate stated that there wasn’t any record of “him holding a pastorate at any time in Brooklyn.” Also, what the girls did to Willie’s hat was hitch up their skirts and kick it.)

Musser’s scholarship is pristine and he said that 1897 and not 1896 was the year censorship came into the cinematic picture with references to back him up. The plot thickens. So, at that point, I was really curious and I set myself down and dug into the newspaper archives.

I have to say before going further, about 90% of the mentions I unearthed from The Kiss’s initial release were simply announcements of The Kiss being included in a picture show program or a recap of those programs after the fact. Most references to the film were positive (the picture was often described as the highlight of various programs, bringing down the house and receiving rapturous applause) but of those that were not, the majority took exception to the quality of the kiss or the fact that Irwin was not a conventionally attractive actress, not the act of kissing onscreen in general. I found a couple of mild tut-tuts but the picture was hardly treated as a scandal that would send His Holiness to his fainting couch.

I emphasize once again, these references were the exception and not the rule (vanilla descriptions of the picture and screening schedules predominated) but here is a small sample of the more lively coverage for your amusement:

“From the remarks made by many of our young ladies Monday night when they saw the May Irwin kiss as shown by the Vitacope [sic] we should judge that all of our girls think that they could give May cards and spades and then beat her at the kissing game.”

Barton County Democrat

“Of all the scenes show, and each is a gem in its own way, none have so caught the popular fancy in San Francisco and elsewhere as the famous scene where May Irwin is kissed by John H. Rush [sic]. Everywhere the audiences have gone wild over that, so lifelike is the play of lip and eye and the swift change of expression on the faces of the pair.”

Los Angeles Herald

“One sees it, and one is almost inclined to blush for the participants/ One sees the jolly May’s lips move as her face is nestled against that of John, and one almost hears her speak. Suddenly John Rice prepares for a kiss proper—and such a kiss as it proves to be! Well, the glorified and perfected kinetoscope, named the vitascope, is a big thing.”

Los Angeles Herald

“One cannot kiss the mouth of the Missouri, yet it is not much larger or muddier or more shapeless than the mouth of Miss Irwin. She is, however, not to blame for these things, they are simply the misfortune of the man unfortunately condemned to kiss her.”

Dallas Weekly Chronicle

(The above item goes on and on about the details of a proper kiss, down to the exact angle in degrees that the eyes must gaze heavenward and which bird May Irwin should have mimicked when engaging in the smooch. It’s weird.)

“The May Irwin kiss, however “famous” it may be, is anything but an edifying spectacle and might profitably be replaced by something less vulgar and much more amusing.”

The Brunswick Times

For those of you keeping score, we have two “she’s a lousy kisser,” one pearl-clutcher, one technology enthusiast and one “nudge nudge, wink wink” out of our small sampler of opinion pieces. That actually seems par for the slightly naughty course and I dare say that reasonably titillating modern material would receive a similar range of reactions.

Obviously, I have not read every newspaper ever published in 1896 and 1897 but I think we can look at these quotations as a core sample of the varied opinions of the time. Were there other condemnations and maybe some angry letters to the editor? More than likely. Were the majority of the reactions along those lines? Almost certainly not. Was there a serious, organized censorship movement aimed at The Kiss specifically? I have seen no evidence.

Rather, there were some isolated complaints but in general, the picture was treated like any other slightly naughty release of the time: a broad wink and an “Oo-la-la” but for a film released during an era of constant moral outrage, there is barely a whiff of sanctimony.

What I find interesting about the contemporary coverage of the film is how little consensus there was. One item treats the film as a serious kissing exercise while another describes it as high comedy. So, it seems that Americans of 1896 were not so very different from us today.

In fact, according to America’s Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry by Daniel Eagan, there was quite a fad for kissing on the stage and The Kiss was meant to promote both the play from which it was derived and the New York World, which covered play, film and smooch in exhaustive detail, an early example of movies cross-promoting with older forms of media.

There does seem to have been some amount of pushback against the Gilded Age kissing fad in general but an 1899 issue of the San Francisco Dramatic Review dismissed such criticism:

“The love scene, once so dear to our hearts, is now reduced to ashes and dry bones and we take no pleasure in it. The kiss, the true kiss (none of your pecks mind) the corner-stone of love, is gone where the wood-bine twineth. That the stage kiss has been abused, we will allow, but is that any reason it should be shelved altogether to pacify a few elderly frumps and tyrannical Puritans who have no business in the play-houses anyway? And because we overeat, shall there be no more food?

A stage kiss such as one would like to see the climax of a perfect love scene, most imperfect without it, would be the death of several people. Well, let them die. The world could bear up against the loss. At any rate, I could, and just now I have the floor.”

So, it seems clear that the content of The Kiss was well within the mainstream of American entertainment at the time and the complaints that emerged were not taken particularly seriously. The film itself remains a fascinating time capsule and the fact that nobody really agreed on what to make of it in 1896 only adds to its modern appeal. That slight feeling of confusion we feel as we watch? It’s okay!

The Kiss is considered essential early film viewing for a reason but like most other early films, the history has become a game of telephone. While it didn’t make nearly as many waves as we may have been led to believe, it was still an early example of cross-promotion as well as onscreen amour and it helped the Edison studio enter the brave new world of projected cinema.

Where can I see it?

You can see it for free courtesy of the Library of Congress. I also recommend Edison: The Invention of the Movies box set.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

You are the research Queen ! Really enjoy the historical context you unearth.

Thank you so much!

I like the way you dug in and found contemporary reactions.

I had fun reading them all. 😀

Looks like you had a lot of fun with this detective story!

Really enjoyed the review and found the historical detail of the film very interestng indeed!

Excellent!

The Chap Book has told me to stop reading your blog. because it is “incorrect” and “full of lies”. So, naturally, I threw it in the garbage and will continue reading and loving every letter you write💕

😉