A French suspense film that plays into the primal fear of something or someone under the bed. In this case, an actress returns home late and interrupts a burglar, who takes refuge under her bed and waits. Brrr!

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD, out of print

What hides beneath…

Pioneering French director Albert Capellani is probably best known for his ambitious feature-length adaptations of Hugo’s Les Misérables in 1912 and Zola’s Germinal in 1913 but I feel his true strength as an artist lay in his ability to create appropriate atmosphere. His historical horror film The Bride of the Haunted Castle (1910), about a newlywed who accidentally falls into an ancient death trap on her wedding day, is one of the highlights of that year.

Just one year passed between The Bride of the Haunted Castle and Terror but Capellani’s skill for building mood and suspense had increased enormously and the latter picture is an example of truth in advertising.

Legendary performer Mistinguett, whose film career is now a footnote to her other accomplishments (and her allegedly heavily-insured legs), plays a fictionalized version of herself. She departs from the stage door and into a waiting car, toting her puppy along with her in a purpose-built muff.

The scene changes to a luxurious bedroom and a man at work inside. The burglar (Émile Mylo) is searching through the room looking for valuables when he is interrupted. Afraid of being detected if he leaves by the window, he opts to hide under the bed and wait it out.

The actress is downstairs fussing over her puppy. It is time for bed, so she enters her bedroom, undresses and gets under the covers. The staff also retire and the house is quiet but the actress cannot sleep and decides to light a cigarette but accidentally drops a lit match on the floor.

This is the film’s most famous sequence and for good reason. So far, the direction has been typical for the period: crisp and clear editing, attractive wide shots that capture all the actors and action but no particular fireworks beyond the subtle pan. Suddenly, the camera pulls back from the bed to show the burglar underneath. He begins to reach for the match to put it out. Then, Capellani cuts to a tight overhead shot, we see the actress leaning to get the match herself but then she sees the hand emerge from underneath her bed. She glances up, terrified. Beautiful, modern, and effective.

The situation, crafted by noted playwright Pierre Decourcelle, is one of primal terror. “Of course there’s nothing under your bed, silly!” Capellani has us exactly where he wants us.

The actress doesn’t dare reveal what she knows. She fidgets on the bed, trying to plot her escape. She tries to casually open the door from her bed but the burglar closes it again. Finally, she pretends to be thirsty and declares that she will refill the water on her bedside table. She places her feet on the floor (the horror!) and slips out, locking the door behind her.

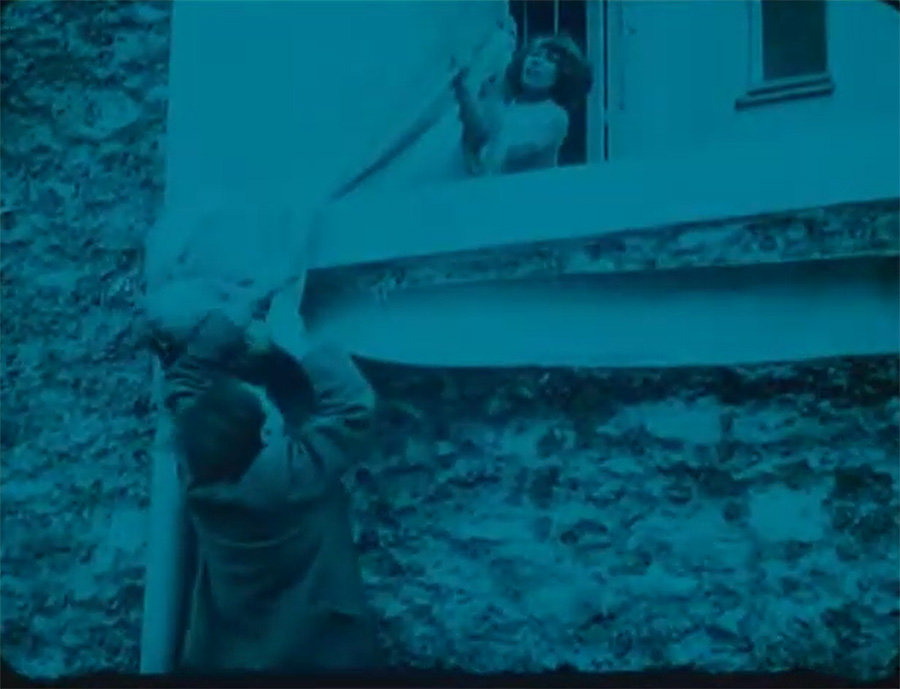

The burglar quickly realizes what has happened when he finds himself locked in. He didn’t want to escape through the window but that seems to be the only choice as the actress has called the police. Well, he will steal her jewels in any case for his trouble. With the valuables in his pockets, he prepares to depart and leaves the room just ahead of the police. What follows is a long chase up and down the roof and balcony of the actress’s apartment as the burglar uses every trick in his arsenal to get away. However, his options are limited by the busy street below and the bustling and alert household inside.

Will the burglar get away? Will the actress recover her jewels? See Terror to find out!

Terror was released by Société des Auteurs et des Gens de Lettres (SCAGL), a company co-founded by Pierre Decourcelle in an effort to translate French theater and literature to the screen. This was parallel to the Société Film d’Art, which brought the best actors of French theater to the screen and made a splash by hiring Camille Saint-Saëns to score The Assassination of The Duke of Guise in 1908.

SCAGL had less posh ambitions that Société Film d’Art, embracing thrillers and comedies along with highfalutin literature, but it does reflect the new respectability that the late 1900s and early 1910s brought to the movies, with big names in the non-film entertainment world trying their hand.

Mistinguett was experienced in the revue space and that holds her in good stead as a film performer. Stage actors could tend to play to the cheap seats but Mistinguett was used to forging a personal connection with her audience and keeps tighter control. She and Mylo are slightly on the broad side for the era but not too far and it suits the dramatic and punchy material well.

The picture ends with the burglar holding onto a drainpipe and finally managing to shake the police. However, it’s out of the frying pan and into the fire because the thin metal of the pipe buckles and it is agonizing to hold on but hold on he must. The actress, alone in the room, hears his cries of pain and has pity on him. She throws him the curtains to grab hold of and he hauls himself inside. She is naturally still afraid of him and her jewels falling out of his pocket don’t help matters. The burglar decides that one good turn deserves another and places his loot on the table before leaving peacefully.

The benevolent burglar was a popular plot device in this period of filmmaking and was marked by a housebreaker who does not reform or repent but does show that under his dishonest profession, he is an honorable man. This was not a uniquely French or even European approach. It shows up in American films of the period such as A Brave Little Woman (1912), in which Harold Lockwood attempts to rob Dorothy Davenport but realizes that her husband is bedridden and she has been caring for him and protecting him, so he refuses her valuables and departs.

We see a much more proactive and hero-coded burglar in After Midnight (1915), in which Broncho Billy Anderson plays a burglar who rescues Marguerite Clayton from physical and sexual abuse at the hands of her husband and she in turn protects him from being arrested after the vindictive husband calls the police.

In all of these cases, the burglars make no promises to leave their lives of crime. There is no reform, as we would see in later films, but rather the simple fact that a criminal can have a stronger code of personal ethics than so-called respectable citizens. Or, in the case of Terror, simply that the burglar and the actress each respect the humanity of the other. In all cases, the police are ineffectual or not present at all. In short, beside the point.

This attitude speaks to the weaker censorship of the era but it also reflects the fact that movies were the entertainment of the working class, the ambitions of SCAGL notwithstanding. Criminals getting away with their crimes would be specifically banned as part of Will Hayes’ censorship push in the United States.

Terror is a punchy and clever little delight. Capellani wastes no time and throws the viewer straight into the action. Setup doesn’t matter, prologue doesn’t exist, an epilogue is never even considered, it’s straight to the meat of the setup. Most excellent and highly recommended.

Where can I see it?

Released on DVD in Europe to accompany the Albert Capellani: A Cinema of Grandeur presentation but it’s difficult to track down but there are unofficial releases on most streaming sites.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.