An entire silent comedy based on… a postcard? That’s right, this little comedy played with the popular “whole Dam family gag” that was enjoying a moment in jokes, postcards, novelty songs and more.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Dam it!

That’s right, The Whole Dam Family and the Dam Dog was based on a popular genre of comedy postcard, copies of which were selling like hotcakes and being mailed across the United States for a penny. Modern studios may have made films based on a Twitter thread but the silent era was there first when it came to jumping on hot topics, trends and virality– quickly, now, before they disappear!

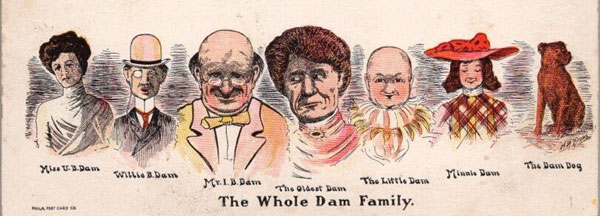

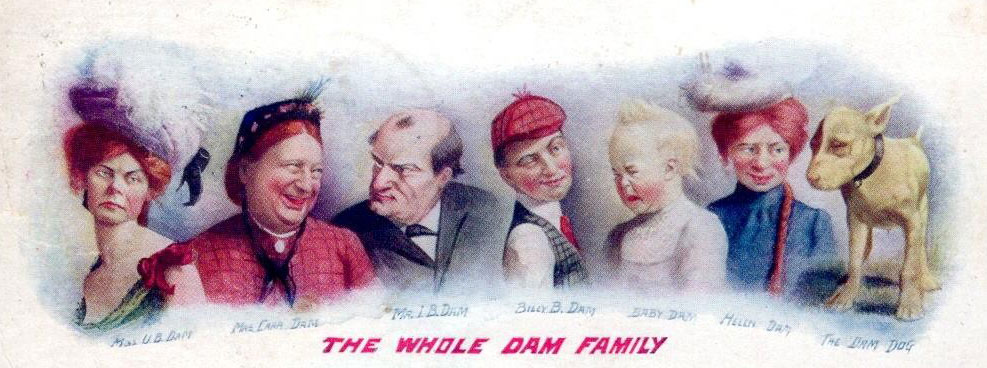

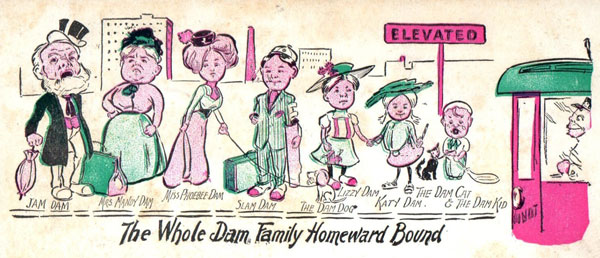

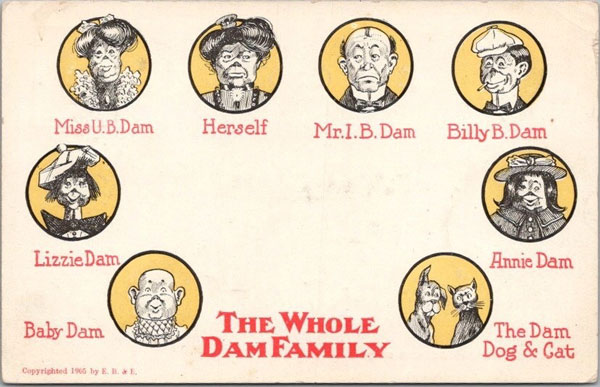

Here is the most famous version of the postcard (there were many others) that the movie clearly drew from:

Edwin S. Porter’s film adaptation doesn’t stray far from its source material, displaying the members of the Dam family one by one like a sweary Brady Bunch, each with a play on their shared surname and displaying obnoxious behaviors like incessant talking, gum-chewing and smoking. The actors’ faces are exaggerated with makeup, putty and possibly wires to provide snub noses. (A loop of wire was attached to the tip of the nose and fastened behind the head, pulling the nose up. It was difficult to detect head-on.)

Porter mixes things up with animated title cards (including a cruel joke about tying firecrackers to the tail of the Dam dog) and then switches gears for a brief domestic scene. The Dam family is sitting down to dinner but the Dam dog has claimed the father’s seat at the head of the table. After shooing away the dog, father chastises Jimmy for smoking at the table and then the family settles in to eat. But then the Dam dog returns, pulls the tablecloth and sends the entire Dam dinner crashing to the floor.

Well, damn.

Porter’s combination of quick sight gags and a skit at the end makes The Whole Dam Family a bit of a transitional film, combining the sort of snappy, one-shot gags from the earliest days of film with a short domestic skit that would become the future of film comedy (complete with slapstick). Still, the main areas of modern interest for this film are historical.

There are two starts to the dinner scene, one with father shooing the dog away and the dog stealing the whole chair. The scene resets to a much longer version concluding with the tablecloth business. It has been speculated that the first shorter version was an outtake but dog’s behavior with the chair looks like deliberate training and not a mistake. This film was preserved as a paper print for copyright purposes, so I think perhaps the shorter dinner scene was not an outtake but a way to give the film a shorter runtime (and cheaper price) as an alternate version. The film was sliced up and made available for sale by character but I did not see mention of a shorter dinner scene being released, so it may not have come to fruition.

(On a side note, I noticed that Wikipedia is crediting Mary Irwin as Herself, the matriarch of the Dam family. There are no cited sources for this and books on Edison films and Irwin’s career made no mention of her working in this film, I also cannot find a period reference to her involvement. Irwin was a major stage star and had made The Kiss for Edison in 1896 but she had been identified by name and her involvement was widely touted in the press, she was quite a “get” for the movies. Films had gone from novelty to working class entertainment in the decade that followed but I find it very difficult to believe that a star of Irwin’s caliber– she had only just returned to the stage with great fanfare after a rest break– would be uncredited and unmentioned. Until a proper source is offered up, I would call this claim highly suspect.)

So, like most modern people, I have some questions about how a postcard ended up as a major motion picture released by a large studio. Let’s start at the beginning, the origins of the Dam Family joke itself, which pre-dated both picture postcards and the movies. This kind of thing makes me feel like a conspiracy theorist linking pinned photos with red string but… Dam is a Danish surname. Danish immigration to the United States kicked off in earnest in the 1860s. The private printed (but not picture) postcard also became a thing in the United States in the 1860s. The whole Dam family was inevitable!

Actually, the examples I have seen are from the 1900s (a significant decade in postcard history, which we will be digging into in a bit) but Dam family jokes can be found in American newspapers throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and were likely floating around as verbal gags before that. I gathered a few examples and we can see how quickly the joke evolved and built itself on previous versions. Here is the earliest one I found (which likely was not the earliest ever published):

A young man in Maine asked a Miss Dam how tho health of the family. She replied “the whole Dam family seemed to be ailing,” herself only excepted. -Magnolia Gazette (Mississippi) May 17, 1883

Next, we see how the joke changed locations and became localized with an added punchline:

There is a family living in Augusta named Dam. A gentleman asked one of the young ladies about their health. She said: “Father is sick. mother is unwell and Willie is sick. In fact,” she said, ‘‘the whole Dam family is sick.”

A Marietta girl tried to tell the above at a picnic the other day, but got the last sentence slightly transposed and said, ‘‘the whole family is Dam sick.” -The Marietta Journal (Georgia), May 31, 1883

And the joke was alive and well almost twenty years later, with a cough drop brand having a bit of fun for the purpose of advertising:

Somebody around the post office should have charges preferred against them for indecency. There is a sign in the doorway which reads: “Mr Dam, Mrs. Dam and the whole Dam family use Red Cross Cough Drops.” -La Junta Tribune (Colorado), February 8, 1902

So, we know the joke existed for quite some time before the movies but where do postcards enter the story? The early 1900s were a golden age of picture postcards, with newspapers breathlessly reporting on this worldwide collecting and mailing craze. Newspapers shared news of the fad spreading worldwide. A sampler:

England: A 1904 item reported that posh lad and future author Evelyn Wrench was pulling in over a hundred thousand pounds a year with his postcard shop. The fad-based business unsurprisingly failed later that year, blamed on overexpansion. They were printing 60,000,000 postcards a year. Later the same year, a postman claimed he delivered 100 cards in one day to a single recipient.

Poland: 1900 saw an postcard exhibition in Warsaw and the craze was also strong in the “Baltic provinces.”

Germany: Postcards on every topic were being exchanged and carefully filed away in collections, according to a 1900 international news report.

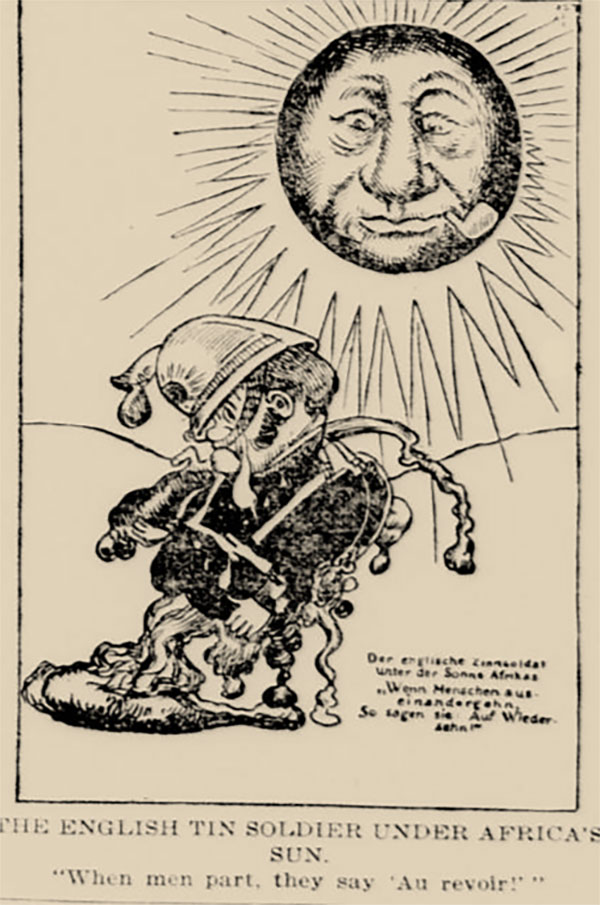

Austria: Political postcards went too far, with a Viennese company printing a card showing a British soldier melting in the sun of Africa (this would have been during the Second Boer War). The cards were confiscated and banned, per the 1900 report, but it did not specify if they were taken by Austrian officials or seized upon export elsewhere. In an early example of the Streisand Effect, the paper reprinted one of the offending cards complete with English translation.

Italy: A clever inventor claimed to have developed color-changing postcards depending on the weather. I want one!

In the 1900s, picture postcards were relatively new and were an inexpensive and fun trinket to send back home from a trip. There were plenty that featured dignified photographs of monuments, officials, expositions, and palaces but with eager customers of every taste, bawdy and zany postcards also filled souvenir shops. The Whole Dam Family cards were part of that wave.

Of course, postcards ran into problems in the Unites States as well. In 1905, the New York Tribune ran a piece on Abuse of the Picture Post Card: Once Harmless Fad Now Degenerating into Inanity, Vulgarity, and Putridity. Most of the article discusses pornographic cards being sold on the street and sting operations by the likes of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.

However, the rest of the piece discusses how post cards could encourage laziness and a lack of thinking skills. (Pre-filled and pre-printed cards were particularly condemned.) The Whole Dam Family cards were singled out as encouraging a lack of imagination and copycat cards to the exclusion of new gags. The sweariness of the Dam joke was not part of the objection to the postcards, despite the concerns of the citizen from Colorado, mentioned above. The article does admit that postcards were useful for communicated across long distances cheaply but was generally negative.

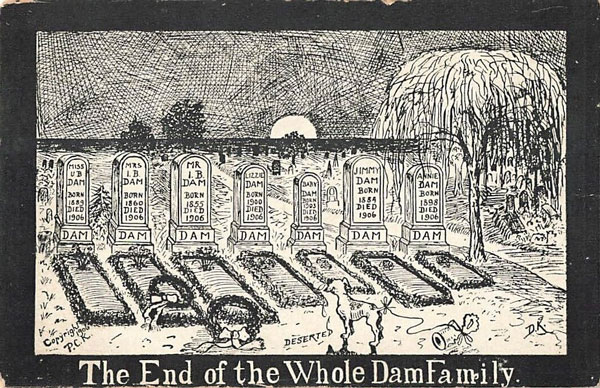

Multiple versions of the Dam Family cards exist. Extant examples sometimes display just the family with names and caricatures but some also featured specialty printing to include the name of the place where the card was purchased. “The Whole Dam Family Are at Rehobath, Delaware,” as one example reads. (Horn’s Pavilion being a popular attraction that would invite souvenir shopping.) The family also adopted characteristics, with the young daughters in extravagant hats, a son or brother-in-law often named Jimmy Dam in the mix and, of course, the Dam dog. By 1906, the cards had taken a dark turn with the Dam family Dam dead.

Edison’s publicity declared that their new comedy was based on “a popular fad which has been widely advertised by lithographs and souvenir mailing cards and has recently been made the subject of a sketch in a New York Vaudeville Theatre.” In Before the Nickelodeon, Charles Musser points out that the sketch opened after the release of the film, so the publicity material seemed to be anticipating the release and connecting their movie to the more-prestigious-at-the-time stage.

https://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/detail.php?query_type=mms_id&query=990034909060203776The Edison company also released a cylinder recording of Arthur Gilbert singing a 1905 song of the Whole Dam Family saga, words by George Totten Smith, music by Albert Von Tilzer. The song’s narrator tells of his attempt to court the daughter of the Dam family of Amsterdam, members of which have been squatting in his flat. Her father declares that the narrator must support the family or “He won’t give a Dam.”

And, of course, it wouldn’t be an early film story without just a bit of piracy. The Lubin company, which was infamous for, ahem, re-imagining the work of other studios (they had released their own Great Train Robbery after the Edison title but claimed they were first) quickly released their own version of The Whole Dam Family. The names are shuffled a bit (mom is Hellen instead of the usual Herself) but it’s pretty much the Edison version all over again, sans the climactic Dam dog sequence.

The Whole Dam Family splits the difference between the older get in, get out gags of early cinema and the more narrative structure that was becoming increasingly popular. It’s important as a hit film of the era (Edison’s biggest, selling 136 copies between 1905 and 1906, succeeded by Dream of a Rarebit Fiend as their bestseller) but how it plays to a modern viewer very much depends on that viewer’s taste for vintage gags. I would say my interest is more historical but with a runtime of just a few minutes, it’s worth seeing.

Where can I see it?

Released on DVD as part of the Edison: The Invention of the Movies box set.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.