Probably the shortest political satire ever made, this 30-second film is a play on Chicago’s reputation for violence and corruption with a still potent plot twist.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Law and Order

Designed as a quick amusement for the popular peepshow machines, the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company produced this single-shot satire in 1900. The plot is simple but the twist can still surprise despite its thirty-second runtime.

A stranger in town pauses to admire an attractive woman walking by. As his back is turned, a mugger emerges and sandbags him from behind, stealing his watch and running away. The man lays senseless on the ground when a policeman passes by. Without skipping a beat on his beat, he stoops down, takes the cash that the robber left behind on his victim and pockets it.

This political zinger is delivered in a single continuous shot of a street set built in Biograph’s rooftop studio with Arthur Marvin credited as cameraman and Wallace McCutcheon the director. The details are a bit lost because, like many early films, this was preserved as a paper print rather than film.

At the time How They Rob Men in Chicago was made, the city’s police department was notoriously corrupt and violent, with deaths at the hands of the police skyrocketing during the decade of the 1900s. They were expected to keep the peace for middle class citizens and clubbing or shooting to kill was expressly encouraged. In fact, during a surveyed period of 1870s-1920s, the numbers showed that the Chicago police killed at a rate three times that of gangsters.

Although, considering that Biograph was headquartered in New York, I am not entirely sure they should have been throwing rocks at another city. Film historian Scott Simmon makes this point in his essay about the film, bringing out that New York was the target of a similar satire in the 1902 Edison picture How They Do Things in Bowery. Simmon further states, as Chicago police officers were expect to “donate” a portion of their salary to political bosses, they made up for the loss of cash by obtaining donations of their own, including initiation fees from local pickpockets. The police officer in How They Rob Men in Chicago was feathering his nest even further in an endless downward flow of theft and graft. Chief of police Joseph Kipley certainly did not help matters with his political maneuvering and shady dealings.

(Southern Illinois University Press has published a rather thorough breakdown, To Serve and Collect: Chicago Politics and Police Corruption from the Lager Beer Riot to the Summerdale Scandal, 1855-1960 by Richard C. Lindberg, should you wish to dive deeper.)

The picture is interesting as a social satire but it is even more fascinating when we look at the subsequent history of cinema in that city. In 1900, organized film censorship campaigns were relatively rare and movies were successful but had not yet become the popular entertainment of the masses. All of that would change before the end of the decade.

While the picture takes on the Chicago police department in particular, this negative portrayal of law enforcement was common in early film generally and spoke to the primary audience for the films: working class people to whom the mid-1900s innovation of a five-cent picture show was a godsend of cheap and plentiful entertainment, especially for new immigrants who were still adapting to spoken English. (Even factoring inflation into the conversation, these shows were the equivalent of about a buck, cheap at the price. A great many items were advertised by their nickel cost, from candy to cigars.)

The policeman on the beat wasn’t out arresting debutantes and moguls, the working class felt the long arm of the law and they enjoyed laughing at its expense. This appreciation was international, from the Georges Méliès comedy On the Roofs to the Robert W. Paul comedy The ? Motorist. There were exceptions but the overall movie consensus was clear: the police were incompetent and caused as much harm as they prevented.

Projected cinema had its start as an international phenomenon, being shown to crowned heads and presidents, but it quickly lost its shimmer and became the entertainment of the masses. In the U.S., those five-cent picture shows had a lot to do with it. Pearls were clutched!

A 1907 editorial in the trade magazine The Moving Picture World described the objections: “Of late a strong protest has been entered in some quarters against the five-cent theater. Its pictures, songs; and associations are denounced as demoralizing in their nature. The effect upon the minds of children of pictures of burglars at work, of prize fighters in the ring, of gamblers, of drunkards, or other equally objectionable or questionable views that may be readily called to mind, is deplored, and the suppression of these pictures, as dangerous to public morals, is called for. It is also pointed out that the habit of visiting these places leads children and young girls and boys into undesirable company, and paves the way to ruin in some cases.”

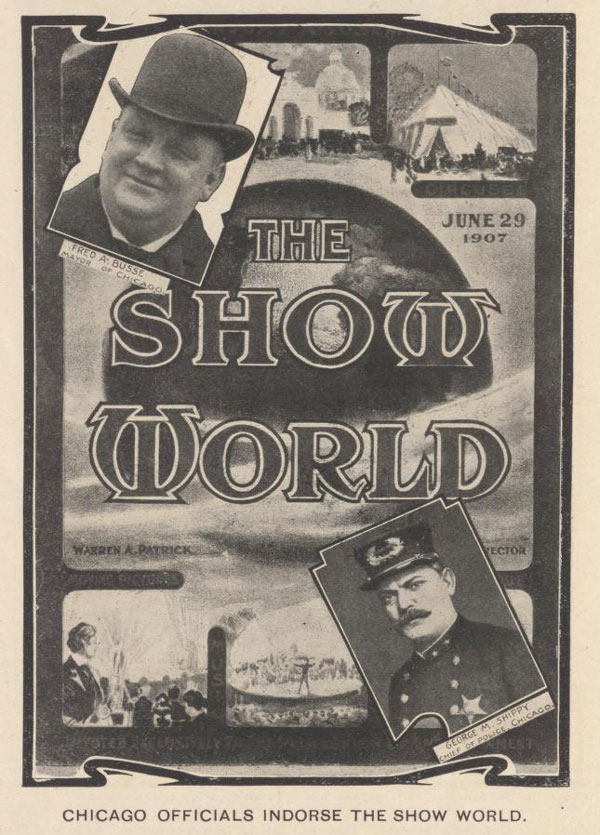

Chicago, already a censorious city with an official censor of burlesque acts, felt that this was a job for the police department and gave them powers of film censorship in 1907, with the encouragement and tattling of church leaders. “In Chicago a protest against the exhibition of certain pictures in five-cent theaters was made to Mayor Busse by a delegation from the congregation of St. Michael’s Roman Catholic Church, Eugenie street and Cleveland avenue. The delegation declared that many of the pictures shown were suggestive, and produced a list of the theaters in the district in which they were shown. Mayor Busse turned the list over to Chief Shippy, with instructions to make an investigation and submit a report.”

The head of the police at the time, Chief George M. Shippy (he of the infamous Lazarus Averbuch affair) had appointed Lieutenant Joel A. Smith as his chief censor, tasked with viewing the movies applying to be shown in Chicago and making any necessary cuts to protect the morals of the city.

Smith got himself into hot water almost immediately by demanding cuts of all scenes of sword duels, stabbings and blood… from Macbeth. Trade magazines, which generally opposed organized censorship as sanctimonious and ignorant, leapt onto the story as a prime example of their concerns.

Smith certainly didn’t help himself with his explanation of his cuts: “I am not taking issue with Shakespeare. As a writer he was far from reproach. But he never looked into the distance and saw that his plots were going to be interpreted for the 5-cent theater… ‘Romeo and Juliet,’ on the other hand, is different, there are violence and suicide and duelling [sic] there, too. But the manager knows that the love element, not the fight element, predominates, and he knows that when anyone pays 5 cents to see ‘Romeo and Juliet’ he pays to see love. When he pays 5 cents to see ‘Macbeth’ he pays to see a fight. So love is the feature of the ‘Romeo and Juliet films, and love is fit for children to see, if kept within reason.”

This very much fit the two-pronged attack of censorship: while religious figures worried about sex, police and reformers demanded a reduction in onscreen violence and Smith’s focus on Macbeth illustrates this fixation. (And it’s ironic, given our earlier discussion of the department’s penchant for violence. One wonders if the gangsters wouldn’t have been a better choice as censors.)

I couldn’t find any specific account of Smith’s replacement but the Macbeth brouhaha happened in June and by October, Lieutenant Alexander McDonald was described as “Chief Shippy’s five-cent theater and dance hall censor.” McDonald had a list of fourteen films that were deemed unfit for exhibition, most dealing with burglary, divorce and sex with titles like Clara Got His Money, Society Burglar and Is Marriage a Failure?

However, the most interesting title on the chopping block was a French film titled The Police Dogs. The movie is extant and is a slightly surreal, stencil-colored chase picture in which a gang of burglars is pursued and captured by trained police dogs. The film ends with a posed portrait of the dogs (and no human officers). It was likely banned because it portrays the act of burglary but I also wonder if the human coppers were a bit miffed at being left out of the laurels at the end?

Despite the ridicule, Chicago’s censor board endured and would become one of the most powerful non-industry film bodies in the United States and, through film ratings, we are still feeling its ripple effects. (Chief Shippy died in an asylum in the aftermath of the Averbuch affair.) And this early alliance of police and clergy was reflected in the first iteration of the Hays Code, which forbade ridicule of the clergy outright and warned against negative images of law enforcement officers and portraying “third degree” behaviors.

Shippy and co. were not on the movie censorship case back in 1900 but I imagine How They Rob Men in Chicago would have been slapped with an immediate ban sight unseen, it was certainly the specific kind of film police censors would later target. It’s a short film but an amusing one, showcasing cinema’s early propensity for political commentary and social satire, two things censors famously did not appreciate.

Where can I see it?

Released as part of the Treasures III box set from the National Film Preservation Foundation.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Interesting that Shippy thought that when audiences were “paying to see love,” violence was _more_ acceptable.

That was surprisingly common at the time: the American censorship movement (and the Canadian one, from what I can tell) would sometimes prioritize censoring violence over sex. How things have changed…