An innocent buttonhole-maker is under attack by the wicked factory owner and it’s up to her noble lover and the wacky police force to save her. Knockoff Keystone that hits on topical concerns of 1914.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of EYE.

The Butcher, the Baker…

The old-school melodrama spoof had been a fixture in silent cinema since the dawn of film. Barnstormer productions of throbbing melodramas were popular entertainment and were directly replaced by the movies. As usually happens in pop culture, the new reigning entertainment would take a few shots at its vanquished predecessor (as talkies would do in turn to silent films).

Bertha the Buttonhole-Maker is a split-reel Biograph comedy (about five minutes long, sharing the ten-minute reel with another short, Making Them Cough) that features a maniacal villain, an imperiled heroine, a hero to the rescue, and a group of suspiciously Keystone-esque cops.

With just five minutes, the movie gets right down to business. The nasty villain (Walter Coyle) separates Bertha (Madge Kirby) from her factory foreman boyfriend, shooting him in the backside with a pistol. He then chases Bertha into the industrial elevator and puts up the cage-like doors so that nobody can help her.

The boyfriend calls for help, surely the police will save the day! Unfortunately, the police are a goofy lot who can barely ride in their own automobile without falling out. The villain drags Bertha to an office, proposes marriage, and when she turns him down, turns on a huge waterpipe and then locks her inside with a plate-sized padlock. Fortunately, the police accidentally manage to drain the water before Bertha drowns and the boyfriend defeats the villain.

This is a blink-and-you’d-miss-it little comedy that is all anarchic frenzy from beginning to end and this is enhanced by what seems to be missing footage at the beginning and end of the picture. Director Dell Henderson keeps things moving, I’ll give him that. Everyone acts as broadly as possible but that’s to be expected in a broad spoof of a broad genre.

Melodrama spoofs generally featured the wicked villain relentlessly attacking the innocent heroine but the motivation for such attacks varied. The most common was simply because the heroine rejected the villain’s sexual advances, sometimes tamed down to “refused his hand in marriage” during the silent era, as it was here, and almost always used in later, Code and post-Code era works. That is, sadly, a timeless plot device because art reflects reality.

However, there were other spoofs that had the villain chasing down the heroine for the hell of it, slasher film-style. And the Villain Still Pursued Her; Or, the Author’s Dream took this to surreal heights as the villain and heroine basically ignored the hero in their madcap, knife-wielding chase.

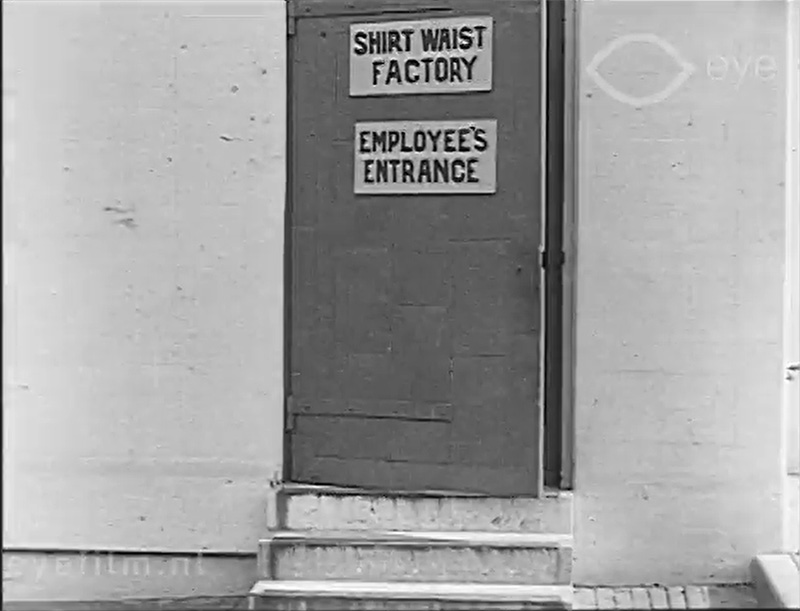

As the villain of Bertha the Buttonhole-Maker, Walter Coyle does attempt to coerce Bertha into marriage but seems primarily motivated to lock his in his Rube Goldberg deathtrap that is purpose-built in one of the building’s offices. Coyle is, if not the owner, at least an executive of the company that owns the shirtwaist factory, as shown by his silk hat and easy access to the keys to the building.

While I don’t think Henderson and the Biograph team were aiming for any kind of heavy message, the selection of a shirtwaist factory poohbah as the villain is significant. The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911 was a sweatshop tragedy in which 146 workers (mostly immigrant women) died due to locked doors, narrow corridors and a lack of safety measures. The incident became a rallying cry for labor rights and was dramatized on film multiple times, so much so that it became pop culture shorthand.

Being forced to work in a shirtwaist factory was also used to portray heroines who were at the end of their rope; nobody with other options would want to be employed by such a company. Movies began to use this fact as plot devices even if they did not directly reference the fire.

The perils of working women, white and blue collar, were frequently visited in the movies, both comedies and dramas. Children of Eve (1915) portrays a woman who goes undercover in a cannery to expose the poor working conditions and ends up trapped when a fire sweeps the building. Lecherous bosses were the main antagonists of The Social Secretary (1916), in which Norma Talmadge has to adopt frumpy dress to avoid sexual harassment. So, with its sex pest boss and death trap factory, Bertha the Buttonhole-Maker was tapping into cultural references that would continue to be familiar to silent era audiences.

Oh, and what is the significance of Bertha’s profession? Well, a buttonhole-maker was a real profession and, per labor data of the era, would sometimes freelance between factories as they did not have enough labor to employ someone full time for buttonholes alone. They were mid-level employees when on staff, paid more than errand boys and less than machinists or top-level seamstresses.

In practical terms, the title of the film was likely chosen as buttonhole-maker was a semi-popular way to refer to somebody with no expertise dabbling in a popular pastime. (My grandfather, born 1909, used to use the term “shoe salesman” in the same manner.) The saying “the butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker” was sometimes also phrased as “the butcher, the baker, the buttonhole-maker” for a bit more alliteration. Finally, “Bertha, the Buttonhole-Maker” was sometimes used in place of “Jane Q. Public.”

It was never an extremely popular phrase but it would have been familiar to audiences of 1914 and, given the sheer number of films being released at the time and pithy titles always being in demand, that was enough.

Also, it’s worth noting that Mack Sennett did not invent the idea of comically bumbling cops—Georges Méliès and other early pioneers were already doing that in the 1890s—but Bertha the Buttonhole-Maker does copy the general tone of the Keystone Cops, down to a Ford Sterling-like goatee and a Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle-style performer. These were clearly offbrand Biograph copycats but they’re not bad for what they are. The undercranked antics are amusing.

Bertha the Buttonhole-Maker isn’t the freshest or most unique take on the melodrama spoof and it never reaches the delightfully surreal heights of And the Villain Still Pursued Her but it’s amusing enough for its brief runtime. It’s main value, though, is in the context of the 1910s labor movement and how it was found in even the most unexpected cinematic places.

Where can I see it?

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.