The Great War is on and all the young men are heading “over there” so when a pediatric surgeon decides that his place is with his young patients, he is scorned for shirking his duty and loses the woman he loves.

Home Media Availability: No official release yet.

Yankee Doodle do or die

Hollywood went all in for the Great War, grinding out hundreds of propaganda pictures about the gallant doughboys battling the wicked Hun. Propaganda pictures of the era had a viciousness that wasn’t even present at the height of the Second World War and changing gears proved to be something of a challenge.

DeMille had been gung-ho for the pro-war propaganda, making such pictures even before the United States entered the conflict, and had simultaneously hit a fresh vein of hits as a filmmaker with his divorce pictures Old Wives for New and Don’t Change Your Husband.

For Better, For Worse straddles both these extremes of DeMille’s late-1910s output, while also including lavish historical sequences the preview the success he would later enjoy with historical epics. It’s a triple crossroad in his career and well worth seeing as a result. (DeMille’s first attempt at a massive historical epic, Joan the Woman, had met with only modest success and that genre would have to be abandoned for a while.)

The film’s hero is Dr. Edward Meade (Elliott Dexter), a pediatric surgeon who has saved countless children with his skills. He is madly in love with Sylvia Norcross (Gloria Swanson) and she seems to perhaps like him back but does not commit. His best friend is Richard Burton (Tom Forman), who is also in love with Sylvia. Betty (Wanda Hawley) is quietly in love with Richard and pines for him.

Both Richard and Edward have volunteered to join the army with Edward receiving a captain’s commission thanks to his medical license. However, the head of the hospital (Theodore Roberts) begs him not to go. They are full of young patients that nobody else is skilled enough to operate on them. After considering carefully, Edward agrees to stay and goes to tell Sylvia.

She goes ballistic, shaming him, mocking him and at one point literally wrapping herself in the American flag. She doesn’t stop her attack even as he is called in for an emergency surgery to save a child’s life. If he won’t go to war, she won’t have anything to do with him.

Richard, meanwhile, shows up in uniform and proposes to Sylvia. She doesn’t want to accept but he tells her that men have gone to war because women urged them since the beginning of history. Harald the Dane! The Battle of Lexington! Why, would King Richard the Lionhearted have crusaded without the love of a woman to urge him on? (So, um, about that last one…) DeMille would later return to the subjects of the last two sequences in the sound era with The Crusades and The Unconquered.

These persuasions are accompanied by elaborate flashback sequences as Sylvia imagines herself as a Viking, a Colonial, a medieval princess and they prove to be enough. She agrees to marry Richard and save the honeymoon for his return.

This is all very awkward when Richard asks Edward to be his best man at the wedding. The film is careful to portray both men as brave and nice but are we really to believe that both best friends had no idea they were pursuing the same woman? Anyway, Sylvia pins a white, feathery flower on Edward to mark him as a coward and that’s that.

With Richard away, Sylvia throws herself into wartime charitable endeavors, so eager to drive from one mission to the next that she runs over a small child (Mae Giraci). The little girl’s legs are paralyzed, all the surgeons are swamped as the younger doctors are all fighting in France, where oh where can she find someone skilled enough to operate on the kid?

Yes, we all know where this is going. Sylvia asks Edward to help, he agrees, she realizes that society does actually need to function during combat and the pair become closer. Meanwhile, Richard is wounded in action, losing an arm and the side of his face. Horrified by his appearance, he tells his friend to say that he died so that Sylvia won’t be tied to him.

This leaves Sylvia free to pursue Edward while Betty collapses in tears, frustrated that Sylvia is receiving all the condolences due to a widow when she didn’t love Richard. This is an interesting theme that is left frustratingly unexplored.

But nobody counted on the U.S. Army’s plastic surgeons and Richard soon finds that he has some scarring but his face has been repaired. Delighted, he returns to Sylvia, who is about to announce her engagement to Edward.

Who will Sylvia choose? What will Richard think when he sees she has so quickly moved on? See For Better, For Worse to find out!

Despite its generous seven-reel length (about 90 minutes, give or take) and relatively few major events, the film feels incomplete and glossed over. It fails to develop Betty’s character beyond the woman who waits, it doesn’t expand on the friendship between Edward and Richard. How did Richard feel about his friend’s decision to decline his commission? We don’t know.

While film centers on the shaming and shunning of draft age men in essential occupations, the action shows very few consequences for Richard beyond losing a single lucrative job offer. All of his other punishments are delivered by Sylvia. Gloria Swanson’s performance is good as an unforgiving, jingoistic prig but then why is everyone in love with her? She only learns her lesson after she is personally in need of a pediatric surgeon because of her reckless driving.

DeMille’s marital dramedies worked best when there was a little sauciness in the mixture. Why Change Your Wife? wore its moral on its sleeve but, well, it didn’t have much of a sleeve and was a showcase for negligees, swimwear and wild antics. For Better, For Worse’s big problem is that it’s a bit of a bore. Gowns kept to a minimum, everyone either moralizing or suffering and there is a shocking lack of DeMille regular Julia Faye as some sort of libertine.

For Better, For Worse does seem to have a personal message for DeMille. As Robert S. Birchard points out in Cecil B. DeMille’s Hollywood, it’s possible that the director was smarting from comments about his own pro-war stance while most decidedly not going “over there” himself.

DeMille was the most hawkish of Hollywood’s directors, making anti-Hun fare like it was 1917 well past the point when more sensitive portrayals (such as All Quiet on the Western Front and The Big Parade) were the norm. Always leading with his emotions, DeMille had lost friends on the Lusitania, an event he dramatized in The Little American, and he never let go of his anger toward the old German Empire.

Life imitated art for the DeMilles in another way as they adopted Katherine from an orphanage in 1922. Katherine, like the little girl in For Better, For Worse, had a father who was killed in action and a mother who had died of an illness.

For Better, For Worse could have been an examination of how war frenzy can break relationships and how society must continue even at the height of military action. DeMille was capable of such a film; he had memorably portrayed the temptation and downfall of an embezzling accountant in The Whispering Chorus, a morally complex tale. However, the material in For Better, For Worse remains surface-level, which is even more of a problem as Sylvia is so very unlikable. Unlikable protagonists work in complicated dramas but not fluffy romances.

So, the viewers are left with a picture that has an interesting concept and an extremely pedestrian delivery. While DeMille was capable of complexity, I think his opinions on the war were probably too deeply engrained for him to meet this material with the critical eye it needed and such a task would have been all but impossible with the armistice only months old.

By the way, near the end of the picture, Wanda Hawley holds a lit match in her hand and laughs with joy as it burns out. This may seem incomprehensible but a 1917 issue of The Journal of American Folklore clarifies what she was doing: “Light a match and make a wish. If the match burns as long as you can hold it without breaking off, you will get your wish.”

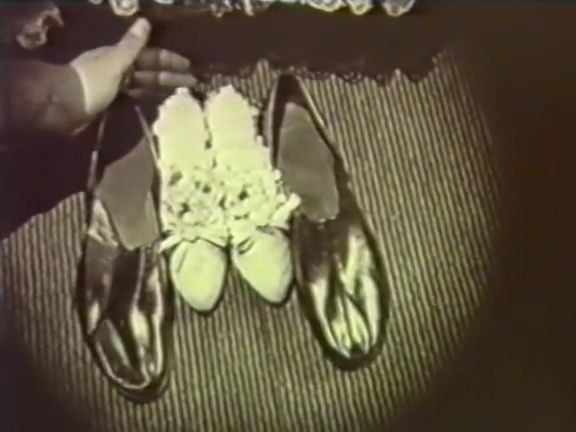

The film is full of symbolism, which is one of the few ways DeMille’s maximalism is present. For example, Richard is wounded when a church is bombed and he is buried in rubble under a large crucifix. Later, when Richard returns home and is about to consummate his marriage to Sylvia, he places his slippers on either side of hers and squeezes them together. I never said it was subtle.

For Better, For Worse was expensive, well-reviewed and made pretty good money at the box office but wasn’t a runaway hit and it’s easy to see why. It had some glitz with its brief flashbacks, and it covered a topic that was under-discussed but the approach was off. I can’t imagine there was a lot of repeat business. Bonkers DeMille is always the best DeMille and this picture is decidedly staid.

The picture represents a turning point in DeMille’s career and preview of what was to come, so it holds interest for fans of the director but it’s not really his best picture from this period. It’s by no means terrible, just a bit… normal, with a few exceptions, and nobody goes to a DeMille picture to see normal.

Where can I see it?

No official DVD release yet but you can find VHS rips online.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

In 1919 it might still have been dangerous to make a movie that presented a non-participant in the war in too positive a light.

I wondered for a moment if the injured Richard was going to take up residence in the basement of the Paris Opera.

I didn’t see any backlash toward this film’s message. It takes care to do the ra ra doughboys thing, which DeMille probably would have done in any case.