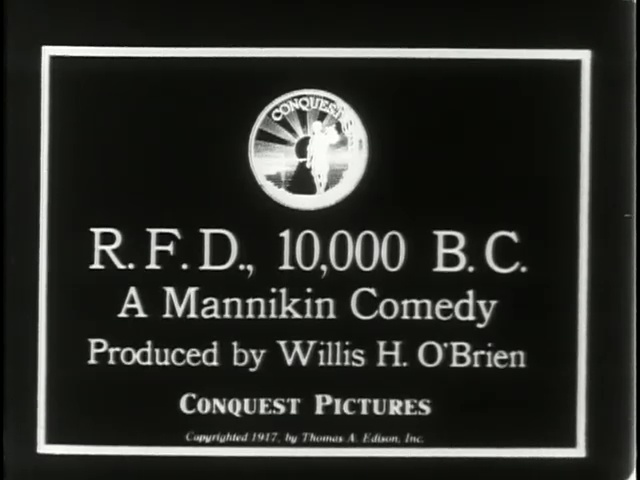

When a caveman’s love letter is swapped out by a malicious postman, prehistoric heartbreak ensues. This short production was one of legendary special effects master Willis O’Brien’s first films and it’s a rather lovely example of complex stop-motion.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Alley Oop!

If there was one thing 1910s audiences loved, it was a good prehistoric pictures. Cavemen or dinosaurs. Cavemen and dinosaurs! Science said no but our hearts said yes and this is where the roots of The Flintstones were put down.

As far as we know, the British Hepworth company started the dinosaur ball rolling with its 1905 adaptation of the Prehistoric Peeps comic strip but there was a major caveman boom in the early 1910s, with just about every major studio releasing some kind of prehistory picture. The Cave Men War (1912, Kalem), Race Memories (1913, Pathe), The Revelation (1913, Kay-Bee), In the Long Ago (1913, Selig), The Primitive Man (1913, Biograph) and many, many more.

The genre was ripe for spoofing and Charlie Chaplin obliged with His Prehistoric Past (1914). I am not sure if the Gale Henry comedy Cave Man Stuff (1918) included literal or just metaphorical cavemen but the ad certainly makes it look like a scream.

So, with this context in mind, it’s easy to see why Willis O’Brien was quickly snapped up by the movies. His independent work in dinosaur model making and stop-motion animation caught the eye of a distributor, who caught the eye of the Edison film company and here we are. O’Brien, of course, went on to create movie magic in The Lost World, King Kong and Mighty Joe Young but this is a chance to see him at the very start of his career.

R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. is a short, mostly stop-motion romantic comedy with a simple story typical of prehistoric productions. Johnny Bearskin wants to pop the question to Winnie Warclub but his stone valentine is intercepted by the R.F.D. (Rural Free Delivery) mailman—and Johnny’s romantic rival— Henry Saurus, who substitutes the love letter for an insulting message. Johnny quickly figures out what has happened and takes matters into his own hands.

And, of course, the mail delivery vehicle is a dinosaur named Dinah.

Told you it was a simple story but we were here for the animation anyway. In both animation and puppetry, technical innovations are all well and good but unless the animator or puppeteer manages to make the creations come alive, it doesn’t matter how sophisticated they are. I was quite pleased by the expressiveness of O’Brien’s “Mannikins,” particularly Dinah the dino. The film seems to have been almost entirely stop-motion, though there are brief puppetry sequences, such as the shot of Dinah breathing.

O’Brien also takes advantage of his medium to deliver some solid (if twisted!) gags. When Johnny discovers Henry’s treachery, he confronts him but Henry bashes him on the head with the mail. However, Dinah grabs Henry, detaches his torso from his legs and flings it into a tree. Henry’s two halves are later reunited but he surrenders his claim on Winnie and his business to Johnny.

There is also a reference in the title cards to “the cave man method.” During the silent era, there was a hot debate going as to whether or not women wanted a violent, bullying and domineering lover with proponents of the caveman approach believing that this was the true way to a woman’s heart. (Spoiler: It’s not.) Harold Lloyd famously spoofed this in Girl Shy when he boldly took a wild flapper across his knee in his imagination but didn’t dare to even speak to women in real life.

I can take or leave any flavor of caveman but dinosaur silent movies and Willis O’Brien are special to me personally. Some of the first silent movie clips I viewed were included in the 1985 documentary Dinosaur! which I watched incessantly as a child. It included sequences from Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur and contextualized them in the dinosaur craze of the time but then it showed shots from The Lost World and I was entranced. I loved stop-motion animation already, thanks to Gumby reruns, and I knew I had to see this wonderful movie. It took decades to accomplish my goal but that is another story.

O’Brien was, of course, the genius behind the dinosaurs in The Lost World and I had also heard of The Ghost of Slumber Mountain, his earlier dino work, but the Library of Congress turned me onto his prehistoric work for the Edison film company and that’s where R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. comes into the picture.

In the mid-1910s, battered by the failure of its talkie technology, the loss of its patent protections and beset by younger, hungrier rivals, Edison and a few of the other older companies began to release under the same umbrella and were shepherded by producer George Kleine. One of his goals was to create all-inclusive packages of educational and entertaining family movie nights and he called the series Conquest.

I became familiar with the Conquest series when I crowdfunded the release of Kidnapped (1917) and all of its accompanying short films. I was impressed with the quality and variety. There was a short narrative feature fifty minutes to an hour in length and then cartoons, comedies, actualities on both travel and science and other delights. You can think of it as The Wonderful World of Disney half a century early. The programs are light, fun and completely suitable (and enjoyable!) for the entire family, which has never been an easy feat to pull off.

Unfortunately, Edison’s advertising was not consistent during this period, so it’s not always easy to untangle which film went where. R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. was said to belong in Conquest Program No. 3 but most ads omit it. Perhaps it was added at the last minute or pulled to be placed elsewhere.

The sad thing is that the Conquest programs and Kleine’s focus on affordable family fare were successful but Edison wasn’t interested in anything short of industry domination, so he pulled the plug on his own company in 1918, leaving the creators who had cut their teeth on Conquest, names like O’Brien and Alan Crosland, to seek employment elsewhere.

R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. was part of the enormous cache of films in Kleine’s personal collection and it was sold to the Library of Congress after his death. Its preservation is fortuitous because it is utterly charming and extremely impressive for a brand new effort. (O’Brien’s The Dinosaur and the Missing Link was part of Conquest Program No. 5 but was shot before he had signed with Edison. The animation was considerably less smooth and it’s easy to see O’Brien’s rapidly advancing innovation.)

This is one of the happier finds of the George Kleine Collection (and there are many) because we get to see the evolution of a special effects legend before our eyes. It’s a light and cute story, the kind of thing we would expect inn any caveman comedy and the personality that O’Brien managed to convey with just some clay and wire shows us why he became the master of all things prehistoric. An absolute treat.

Where can I see it?

Stream it for free courtesy of the Library of Congress.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Enjoyed reading as always….another source for viewing R.F.D. TEN THOUSAND B.C. (1917) is Flicker Alley’s blu-ray copy of The Lost World. It appears as an extra ….Also as a backer of your Kidnapped project I enjoyed that. Still show the flamingo bubble wrap to others it came in ……8-)

Thank you so much!