Goldilocks invades the home of the Three Bears and, after consuming their porridge and sleeping in their beds, flees to the safety of President Theodore Roosevelt. This political satire includes an extended sequence of innovative stop-motion animation.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Big Game

Content Warning: This review contains descriptions of hunting and animal cruelty that are necessary to understand the historical context of the motion picture.

As you can probably tell from the warning above, The Teddy Bears is quite a ride. Quite.

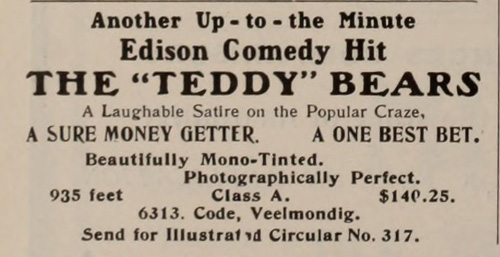

Released in 1907 and with direction credited to Edwin S. Porter and Wallace McCutcheon, it was a hit for the Edison film company. Teddy bears and the surreal world of early film… what could possibly go wrong with such a cute concept?

About that…

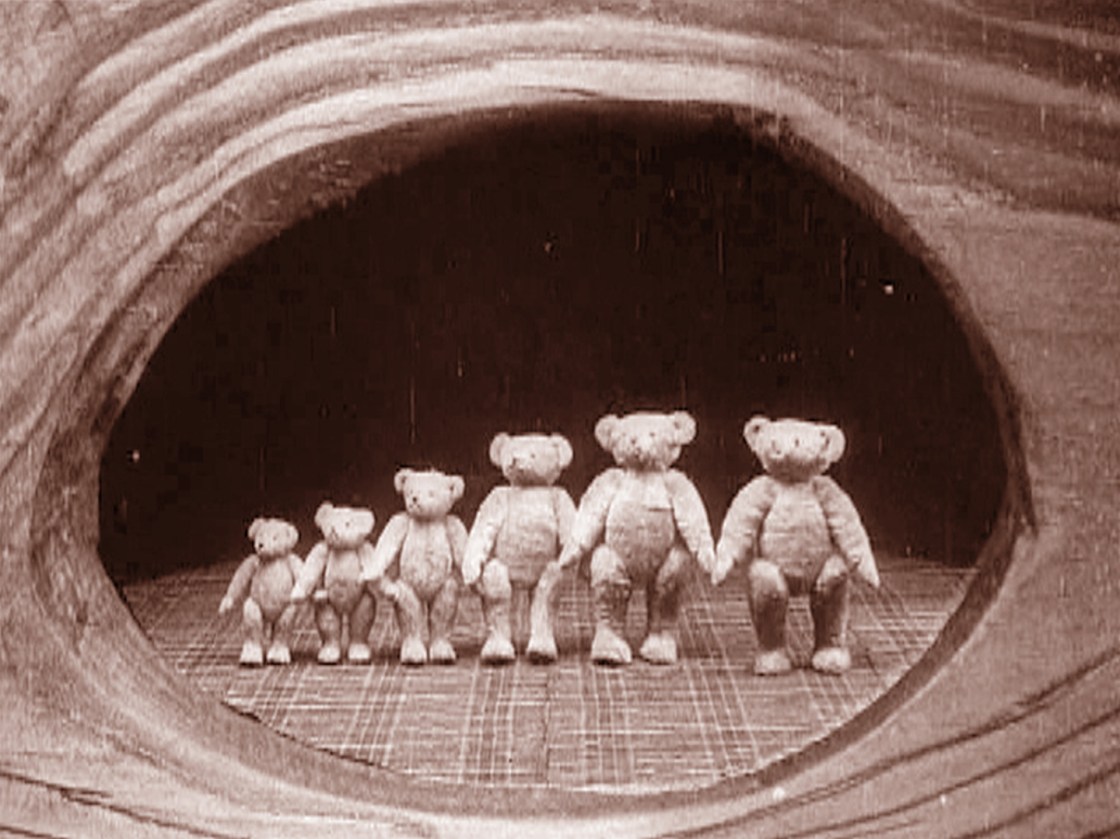

The Teddy Bears opens in the classic Goldilocks manner with a mischievous young bear playing with his own teddy and being scolded by his parents. When the bears leave, young Goldilocks sneaks in and, well, you know the rest. Porridge eat, she takes a quick peek at a collection of dancing bears and then falls asleep on Baby Bear’s bed.

When the bears return, they are naturally horrified by the intrusion and chase Goldilocks through the snow until she runs into the arms and protection of Teddy Roosevelt, who kills Mama Bear and Papa Bear, spares Baby Bear, seizes all the teddy bears and marches off, presumably back to Washington.

So, that certainly escalated.

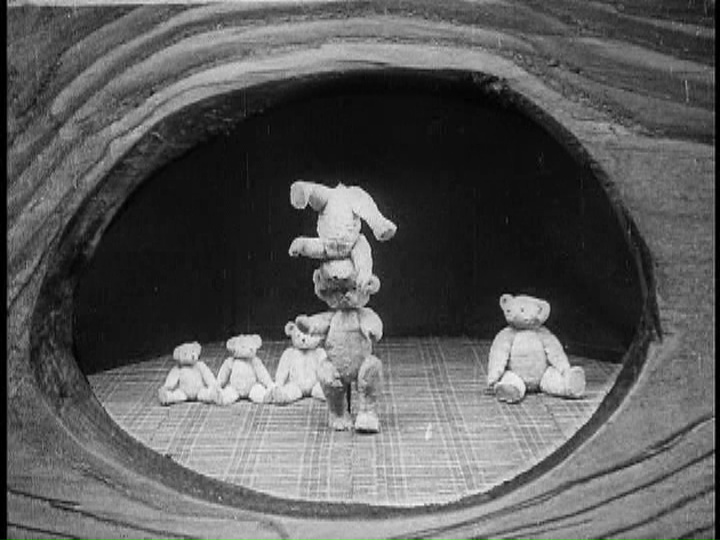

The most famous sequence in The Teddy Bears is the teddy bear dance, described as “mechanical acrobatics” by one reviewer. At the time, toy bears were stiff and jointed, which made them ideal for the stop-motion animation employed by Porter. Of course, we do not know the creative timeline of this film but I would love to know whether the Edison team were inspired to make the film because of the toy bears, the fairy tale or some political comic or op-ed.

Edwin S. Porter was a pioneer of special effects and stop-motion and had been employing the latter in his films for several years before The Teddy Bears. He memorably included a fully-animated title card in The Whole Dam Family and the Dam Dog (1905). The Teddy Bears was an ambitious film for Porter and historian Scott Simmon states that Porter put in a full week of eight-hour days working on the animation sequence alone when entire films were being made in a single day. Between the elaborate dance of the teddy bears and the knothole frame, there’s a lot to see in the sequence.

Goldilocks and the Three Bears had, by 1907, reached its final modern form after nearly a century of tweaks. She had changed from an old woman to a pretty little girl and her intrusion into the bear house was not punished with impalement but, rather, a good scare and sometimes a promise to be a good girl in the future. Knowing this, The Teddy Bears can seem baffling—did the President of the United States just shoot the good guys in an American movie?—if we do not understand the context.

The story of the teddy bear has been told and retold with every version becoming sweeter and more twee and today, it is more of a fairy tale than Goldilocks. Teddy Roosevelt wanted to go hunting but he was presented with an itty-bitty wee cub tied to a tree and refused to shoot! He loved animals, you see! And so, everyone needed a cuddly stuffed toy version of Teddy’s bear. And they all lived happily ever after.

Reality was far, far grimmer.

It’s difficult to find an account of the infamous hunting trip on the public web that isn’t tainted by the galloping cutesy-wootsies. Wikipedia is shockingly accurate for once, even if its sources don’t match. But proper biographies of Roosevelt are generally franker, and I am basing my synopsis on the account from Theodore Rex by Edmund Morris because it is a pretty fawning book and therefore paints the events in the most positive light possible. Keep that in mind because things are about to get disgusting.

Roosevelt was on a hunting trip in Mississippi in autumn of 1902 and was frustrated that he had not killed a bear. The president insisted on first blood and wanted to be the first to shoot an animal. To that end, Holt Collier, his veteran catcher, chased small adult black bear to exhaustion with dogs, clubbed its skull with the butt of a rifle until it was helpless but did not kill it because he wanted to give the president the honor. Roosevelt refused to shoot it as a matter of honor but the bear was dispatched with a knife as a mercy killing. The hunt then continued for three more days with Roosevelt in a pretty bad mood and the story leaked to the press.

This book meant to make Roosevelt look good, remember.

Roosevelt’s refusal to shoot the bear was taken up by political cartoonist Clifford K. Berryman to satirize the administration’s policies. The controversy that Berryman was commenting on was quickly overshadowed by the appeal of the bear and the story was cleaned up, the bear aged down and its eventual fate was ignored. Toy bears were imported from Germany, as well as produced in America, and early designs were very much like the images we see in The Teddy Bears.

(It’s worth noting that Roosevelt displayed no qualms about a captive wolf that was released and chased down by horses inside the White House during a film screening in 1908 and he hunted game, including bears, for the rest of his life. His received stinging criticism for this in the press, even if trophy hunting was generally seen as an acceptable sport. Roosevelt was a conservationist, but the philosophy of the movement at the time was “save the animals so we will have more to hunt later.” Quite a few “nature reserves” were once deemed “game preserves.”)

The Teddy Bears was hyped by the Edison company when it was released. This isn’t surprising considering the amount of time and money spent on the production. The advertisements were also very honest about the subject: “A laughable satire on a popular craze.”

The biggest criticism of the picture, by both 1907 and modern critics, has been the jarring shift in tone from a whimsical fairy tale to a sudden burst of violence at the climax. I cannot call it a flaw because this shift captures the reality of the teddy bear story better than a lot of children’s books on the subject and the surprise actually improves and becomes more shocking with age as the true story is further obscured by heaping mounds of twee. “A cute little tale of… oh my gravy!”

Roosevelt’s obsession with hunting was seen as intense even for those hunt-happy days and his desire to shoot anything in sight had been satirized in the movies since his days as vice president. In Before the Nickelodeon, Charles Musser draws attention to an early Edwin S. Porter production, 1901’s Terrible Teddy, the Grizzly King, based on a series of political cartoons. In the picture, a buffoonish Roosevelt dashes to a tree and starts shooting like a maniac, later posing proudly with the dead animal for the benefit of two actors helpfully labeled My Press Agent and My Photographer.

Given Porter’s earlier film, it does seem that the shooting scene was intentionally satirizing the ruthless story behind the sanitized origin story of the teddy bear. The 1901 portrayal of Roosevelt as preening and bloodthirsty shows that Porter likely intended to convey the same message in 1907. Further, as Variety’s 1907 review of the picture points out, the homey and anthropomorphized presentation of Mama Bear and Papa Bear hardly makes their shooting an act of heroism. Trigger-Happy Teddy capriciously killing and sparing wildlife on a whim was clearly Porter’s message and he was hardly the only person of the time saying so. And, I mean, fair enough.

Tramping over the bodies of actual dead bears to get to the cute stuffed bears was kind of what really happened at the time and Porter nailed it in this picture. And the imagery of Roosevelt raiding the home of the dead bears surely is ripe for anticolonial interpretation, though I doubt that was intentional given the Edison company’s full-throated support for the Spanish-American War. (For an intentional anti-colonial view of Roosevelt, do check out Claws of Gold, a Colombian production exposing the corruption involved in the building of the Panama Canal.)

However, despite its clear political content and labeling as a satire, The Teddy Bears was seen as a children’s film in more than one quarter, even if the response of younger viewers seemed to vary. The Variety review mentions children being put off by the violence, while a theater in Indianapolis wrote in the say that children were attending five-cent screenings by the hundreds.

The Teddy Bears was a strange film when it was released and it’s a strange film today. However, normal doesn’t make history and it’s a fascinating artifact of its time, both for its innovative animation and its pointed political content. Well worth the effort of a viewing.

Where can I see it?

Released as part of the Edison: The Invention of the Movies box set. You can also watch a clip courtesy of the National Film Preservation Foundation.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.