When a happy wife discovers that her husband has a mistress, she takes the only obvious path and challenges her rival to a duel. Throbbing melodrama from Denmark.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of Stumfilm.

Why divorce? Duel!

Danish director Viggo Larsen has been one of my favorite discoveries of this year. His outrageous, uproarious and often surreal comedies have been a source of unending delight for me but, like most early film directors, he wore many hats and worked in many genres. In this case, a pulsating melodrama with a dose of tragedy.

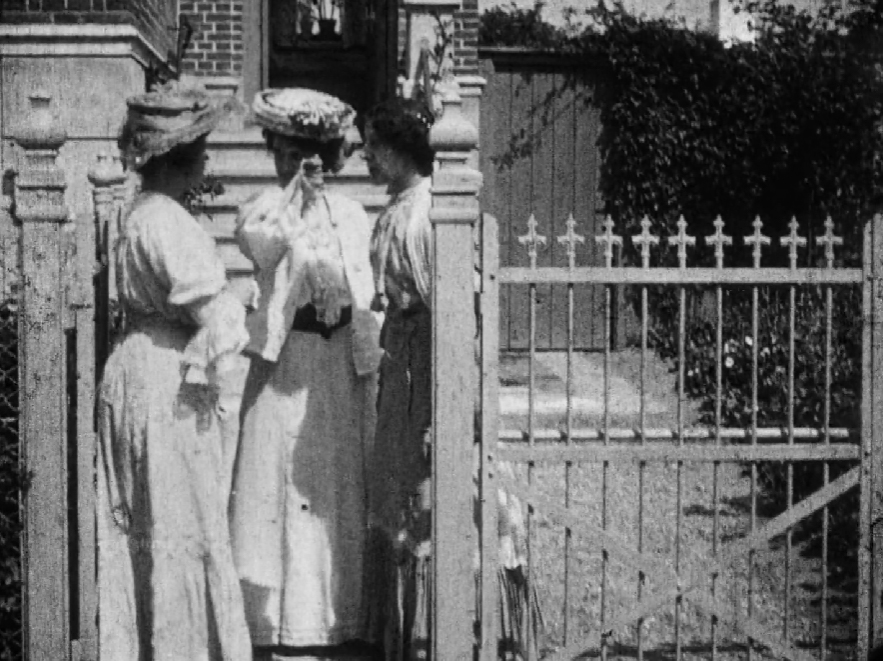

The Other Woman opens with a husband bidding his wife a cheerful farewell and riding away on his bicycle for a quick errand. That “errand” is his mistress, who lives nearby. The wife’s friend sees all and runs to report the husband’s infidelity. Husband and wife pass one another arriving and departing at the mistress’s house and the wife challenges her rival to a duel. She also sends her husband a note wishing him well if she dies.

The duel is fought with pistols with the wife’s friend as the witness. Both guns fire and the wife is killed instantly. The husband shows up too late and declines to be claimed by the victor. Enraged, the mistress shoots him before turning the gun on herself. It has been a busy six minutes.

The film is fairly rudimentary on a technical level. There are few cuts and some awkward angles that decapitate the cast. This was Larsen’s first year in the movies and he was as green as could be but there is a definite appeal in the directness of the melodrama.

I suspected that Larsen’s 1906 comedies A New Hat for the Madam and The Anarchist’s Mother-in-Law were made after The Other Woman because they make use of both interior and exterior shots. In contrast, The Other Woman keeps everything al fresco even when an interior shot would have made much more sense. My suspicions were confirmed by the Danish Film Institute, which states that The Other Woman is the second oldest surviving Nordisk studio film.

So, now we must address the burning question that this film brings up: Did women duel? I mean, I think most history nerds are familiar with women who disguised themselves as men or who dueled men in exhibitions and things of that nature. I was more curious about the women in standard dress for their period and station dueling one another to settle a personal dispute.

It’s important to know that the rise of cinema occurred after the fall of dueling culture in Europe. It still happened (in varying degrees of legality) but it was so darn cinematic that movies would have you believe everyone was demanding pistols at fifty paces if their tea was served cold. Similarly, movies convinced the world that every American cowboy had at least fifteen kill notches in his rifle.

That being said, there were cases throughout history of ladies challenging one another to physical duels using the same weapons employed by men of the period. The most famous one and likely an inspiration for The Other Woman was an Austro-Hungarian duel fought in 1892 between Princess Pauline Metternich and Countess Anastasia Kielmannsegg.

The woman quarreled about flower arrangements! Slaps and slaps! They fought with swords! They fought topless to avoid infecting their wounds with nasty clothing! Yas, girl! Slay, queen! Empowerment! But also sexy!

The duel was quickly accepted as fact and has been told and retold for thirteen decades. The only problem is that it doesn’t actually seem to have happened.

Oh well, since when did facts get in the way?

Most period and modern accounts of the duel focus on the topless part. I propose retaliating by claiming all famous male duels were performed pantsless. (We can’t risk infection can we, boys?) But the image of topless aristocrats and clashing swords was firmly fixed in the public imagination with young Gilded Age reenactors posing for blue postcards and modern historical websites breathlessly repeating the tale without secondary sources, let alone primary ones, and usually illustrating with those postcards, carefully omitting that the princess was actually in her fifties, lest the fantasy of hot young topless things be broken.

And class does matter. In addition to being a trash staple, it’s important to understand that duels could be framed as either aristocratic or criminal. (The working and middle classes apparently having too much good sense for such an activity.) The 1898 British smut film A Duel to the Death features two women doffing their tops and immediately slashing at one another with daggers. The lack of formality or witnesses and the use of short blades rather than pistols or swords marks this as a lower-class duel with the message being: “Please feel free to leer at their commoner underpinnings.” Your naughty entertainment came in many flavors back in those innocent old days.

Larsen’s film is interesting in how decidedly unsexualized the duel is. The women remove their hats but do not disrobe further or strike any sensual poses. The fatal shot is framed a similar manner to a cinematic duel between men. It’s quick, ruthless and nasty with even the death scenes quite brief for the period.

It’s not quite an apples-to-apples comparison because the weapons are swords but the 1904 Biograph film By Right of Sword demonstrates how such a scene was handled when the duelists were men. Minimal fuss, the same businesslike approach and the final blow (merely to first blood and not the death) is delivered with the loser’s back to the camera, thus obscuring the lack of an actual wound from the audience. In contrast, A Duel to the Death seems to have been choreographed with the primary concern of “Can we keep their breasts facing the camera at all times?”

It’s also interesting to see how ineffectual the husband is in the whole thing. At first, it seems that he will be let off the hook, which doesn’t seem entirely fair considering he was the one breaking his vows. But then he gets a bullet in the back and in the end, the wife’s friend is the last one standing. I don’t envy her making that police report.

The wife’s “take care of yourself if I die in this duel, honey” letter is very much along the lines of a “she couldn’t help herself, the beautiful creature” scene when a similar trope plays out with men. And the fact that none of the women see the need to bring hubby into the dispute and he only arrives in time by, presumably, running his adulterous little legs off… My dears, this film fails the Reverse Bechdel Test.

Yes, it’s extremely melodramatic. Yes, it gets to be a bit much when the mistress just starts shooting everyone. But did I ever enjoy the way it played with gender tropes and expectations of the era. The unsexy duel, the unimportant husband, the woman-focused plot. They’re idiots getting themselves killed for love but they’re taking roles usually assigned to men and not taking off their tops. Some filmmakers working today could learn a thing or two from Viggo Larsen.

I call that a solid win.

Where can I see it?

Stream for free courtesy of the Danish Film Institute.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Best line of the review: “It has been a busy six minutes.” Now that’s funny !

Your knowledge putting the film and events in context is always so fascinating. Love reading your posts !!

Thank you so much! And this film is also on that upcoming Cinema’s First Nasty Women set, so it should have even more context.