A daring daylight robbery is the subject of this film—but the theft doesn’t focus on gold or jewels so much as a pair of trousers. British film pioneer R.W. Paul takes a turn for the larcenous in this comedic crime picture.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Doff your duds!

Much of British film pioneer R.W. Paul’s surviving early work is comprised of actualities: street scenes, shots of the queen, and so forth. The Arrest of a Pickpocket (1895) was exactly what it said on the tin. A pickpocket is arrested by a policeman, who receives assistance from a passing sailor. The film Footpads, long identified as a Paul picture of 1896, has since been revealed to be likely a much later film and perhaps not made by Paul at all.

In the essay collection Provenance in Early Cinema, Paul expert Ian Christie breaks down the process of dating this faux Paul picture and is excellent reading all around. It’s important to bring up this misattribution because much of the writing about A Wayfarer Compelled to Disrobe Partially compares it to the more visually sophisticated Footpads, which we now know is not applicable.

Wayfarer is a simple films: A man walking in the park is confronted by a mugger who demands his valuables. The man refuses but quickly changes his mind when his assailant brandishes a pistol. The mugger then demands the man’s hat, jacket, waistcoat and then his trousers, the last item causing the victim much embarrassment as he tries to cover his drawers with his shirt. With that, the picture ends.

The scenery is a simple outdoor setting with a tree and a bench. There’s no moral lesson being conveyed, it’s basically a variation of the “I have no gate key. Oh, this gate key” that would be used ninety years later in The Princess Bride. It’s also a story of self-preservation and the fun for 1897 audiences was watching the obviously well-heeled victim forced to surrender all of the symbols of his rank, from his bowler to his trousers. The practical reason for all of this was that clothing was more valuable at the time and could be hocked, pawned or otherwise turned to quick profit.

The loss of sartorial symbols of rank makes Wayfarer a cousin of the Georges Méliès comedy On the Roofs, which concerns a comical policeman being outsmarted by a pair of burglars. In that case too, the victim is stripped of his vestments—just his uniform boots in this case—and his gendarme regalia is even turned against him as the burglars tie him to the balcony with his own swordbelt.

In 1897, film censorship was just getting started and peepshow motion picture machines were especially targeted but as the movement picked up steam, films that showed criminals in a sympathetic light or showed in detail how crimes were committed were particularly targeted as it was felt they would inspire copycat crimes among children and “morons.”

We’re covered the rise of anti-crime picture censorship before, but I think it would illuminating to show what other entertainment media was focusing on around the same time that Wayfarer was released. Crime novels were big business, of course, and Sherlock Holmes mania had gripped the world. What we now call true crime was also doing well in magazines and newspapers. However, I would like to look particularly at two forms of entertainment that receive a bit less coverage: spoken word entertainment recordings (as opposed to music or dictation) and magic lantern shows.

Magic lantern shows were not just slideshows. They included hand-applied color on the slides, lively narration and even animation and fancy transitions. In fact, quite a few of the more spectacular elements of early cinema were borrowed directly from them. Lantern shows, at least in their trade catalogs, tried to position themselves as the entertainment of civilized people. Portrayals of crime, at least from the big slideshow vendors, were limited to morality and temperance narratives.

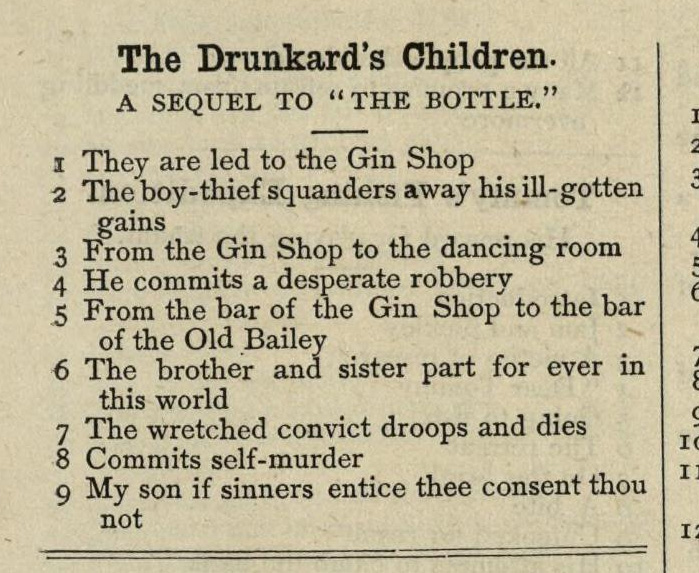

For example, one slide series released circa 1900 entitled The Drunkard’s Children includes such sequences as “He commits a desperate robbery,” and “The wretched convict droops and dies,” as well as “Commits self-murder.” A 1900 piece in The Optical Magic Lantern Journal entitled The Ethics of Lanterndom praised the industries religious piety and educational mission and declared that the morals of the industry were good.

Now, I am sure there were blue magic lantern shows but this gives you an idea of where would-be film censors got their notion of what the movies should look like.

Meanwhile, in the wild west of the relatively new sound recording industry, phonograph parlors had come up with a new and exciting way to attract patrons: recordings of killer confessions. The trend was sarcastically covered in 1897 issues of the Phonoscope, which clearly looked down on the working class patrons who listened to the melodramatic readings of the alleged confessions. No details were spared, apparently, and the subjects included H.H. Holmes (of The Devil in the White City fame) and the forgotten murderer William Carr, who drowned his own toddler.

Carr was also the subject of an actuality. According to the Los Angeles Herald, his 1897 execution was filmed from beginning to end by a cameraman. The paper claimed that a total of 1,000 feet of film was taken (that’s about ten minutes at talkie speed and far longer in the silent era) and included both Carr’s execution and the rioters who broke into the stockade to make sure the execution had taken place.

To my knowledge, the footage of the execution has long since been lost but it was by no means the only time such an event was filmed. That same year, a horrifying film was released called Lynching Scene and the ad claimed that it was “genuine.” The film portrayed a prisoner being pulled from jail by a mob, strung up on a telegraph poll and shot multiple times. The Phonoscope balked at the audio confessions of H.H. Holmes but described Lynching Scene “a most impressive and stirring subject.”

So, with this context in mind, with popular entertainment swinging between the obscenely lurid and pious fare, R.W. Paul’s A Wayfarer Compelled to Disrobe Partially hits a happy medium between the two. It’s hardly as tacky as some of the material we have discussed but it couldn’t exactly be used to teach Sunday school either.

Where can I see it?

Released as part of the region 2 collection R.W. Paul: The Collected Films 1895-1908. The collection is curated by Ian Christie and includes notes written by him. It also includes Footpads as it was still considered part of the Paul canon at the time. Christie wrote about the discovery of the misattribution later.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.