Cinema pioneer Edwin S. Porter sent up his own smash hit, The Great Train Robbery, in this crime comedy with a kiddie cast. It’s a fun spoof but Porter may have run afoul of the growing power of the film censorship movement.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress

Wait until your mother hears…

Early cinema was in constant conversation with itself. Movies were copied, remade, spoofed and it’s almost impossible to untangle firsts as a result. Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903) was an early blockbuster and one of the few films from the era with any name recognition in the modern world. In 1905, Porter decided to revisit his big hit with tongue firmly in cheek.

The Little Train Robbery takes the plot of its big brother but substitutes a gang of kids for the bandits and a miniature railroad for the real train. The kids make off with candy instead of money. It’s all very cute.

We live in a time of unfettered cinematic nostalgia. At the time of this writing, a film incorporating three iterations of the same superhero from the past two decades is making box office gravy and it’s not an outlier. When The Little Train Robbery was released, projected cinema was just ten years old but the picture was also designed to tap into nostalgia.

In Before the Nickelodeon, historian Charles Musser points out that the Edison company marketed The Little Train Robbery to both children and adults. While the children were meant to enjoy the film at face value, “their elders can find equal amusement in recalling their own youthful days, when their highest ambition was to become ‘Jesse James’ or a ‘Bandit Queen.’”

The nostalgia factor was increased by the fact that Porter shot the film in Olympia Park, fifty miles from his own hometown of Connellsville, Pennsylvania. With his 1870 date of birth, Porter was the right age to have absorbed the 1880s dime novels glamorizing bandits like James.

The Little Train Robbery is not a scene-for-scene spoof of The Great Train Robbery. There are a few scenes that are reenacted—the robbery itself and unhitching the engine to escape, leaving the passengers stranded—but things are generally toned down in deference to the youthful cast.

The Great Train Robbery had a high body count with characters beaten, shot and killed by both the bandits and the lawmen. The Little Train Robbery has its youthful gang brandishing pistols but the only real violence is striking the adult conductor of the miniature train on his head. And rather than ending in a shootout during which all the bandits are killed, as was the case with the original, the gang is captured with the exception of the Bandit Queen, who is freed by a confederate.

The Little Train Robbery shows how much had changed in the movies in just two years. The later film is more tightly framed, more cinematic in appearance. The backgrounds are more rustic and realistic, likely a result of the location shoot. It’s not as rough and ready as the original but it has its own charm.

You can also see the roots of later comedy hits in The Little Train Robbery. A band of stumbling cops waving their clubs as they pursue their quarry? The Keystone Cops wouldn’t show up in movies until the next decade. And showing the imagination of children playing out on the screen can be seen as a spiritual ancestor of the Our Gang series.

I must say, Porter did miss an opportunity when he did not end the picture with the Bandit Queen pointing her pistol at the screen and firing in the manner of Justus T. Barnes.

Incidentally, The Little Train Robbery was topical for another reason: miniature railways were a hot item at the time it was made with the Cagney and McGarigle companies supplying cute locomotives and passenger cars to expositions and amusement parks, as well as more practical machines for industrial applications. There are still quite a few of these railways operating and I rode on one often as a child. (Without, needless to say, being robbed of my candy.)

Unfortunately, despite its appeals to nostalgia, The Little Train Robbery was not a hit. Box office information from this period is almost impossible to come by (independent exhibitors whose books are long gone, movies folded in with other entertainments, etc.) but prints were sold outright to exhibitors and the number of copies sold tells us as lot. The Little Train Robbery ended up with a mere thirty copies sold, while 50 to 140 copies was considered average. Porter’s own Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906) was considered a smash hit with 192 copies sold.

(Prints would be screened multiple times and there was a bustling trade for second-hand copies. The big hits in good condition seemed to retain their value well, if the ads I have seen in trade periodicals actually yielded their asking price.)

Musser points out that The Little Train Robbery’s success might have been hampered by the growing concern that storefront theaters were schools for crime and that avid moviegoing children were juvenile delinquents in the making. (In previous generations, similar concern had been expressed about stage melodramas featuring scenes of criminal activity.) Such attitudes didn’t damage the success of The Great Train Robbery but that film didn’t have a cast of kids or present banditry as good fun.

This attitude flourished in the mainstream press and was nurtured by religious organizations. In August of 1910, Good Housekeeping, one of the most influential periodicals marketed to women, denounced the movies in an editorial entitled The Moving Pictures: A Primary School for Criminals by William A. McKeever. One of the more deathless lines from the piece: “A red-light district in easy reach of every home. See the murders and the debauchery while you wait. It is only a nickel.”

Pictures of the era did gravitate toward crime to a certain extent but there were also actualities, prim romances, family-friendly comedies and so forth. Motion picture trade magazines vigorously defended their industry and some theater owners took to publicizing the kid-safe entertainments on offer.

The Good Housekeeping article was published just five years after The Little Train Robbery and the idea that movies were harmful was well-established in 1905. I couldn’t find anything mentioning The Little Train Robbery specifically but I am very interested to know if they “children do crimes!” concept was seen as too risky for exhibitors at the time.

Still, in spite of everything, The Little Train Robbery is a cheerful spoof of one of early cinema’s biggest hits. It lacks the punch of its forebear but it was never really intended to be a rival to it. It seems that Porter just wanted to bring a bit of his childhood to the screen, as the Lumière brothers had done before him.

Where can I see it?

Stream for free courtesy of the Library of Congress.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

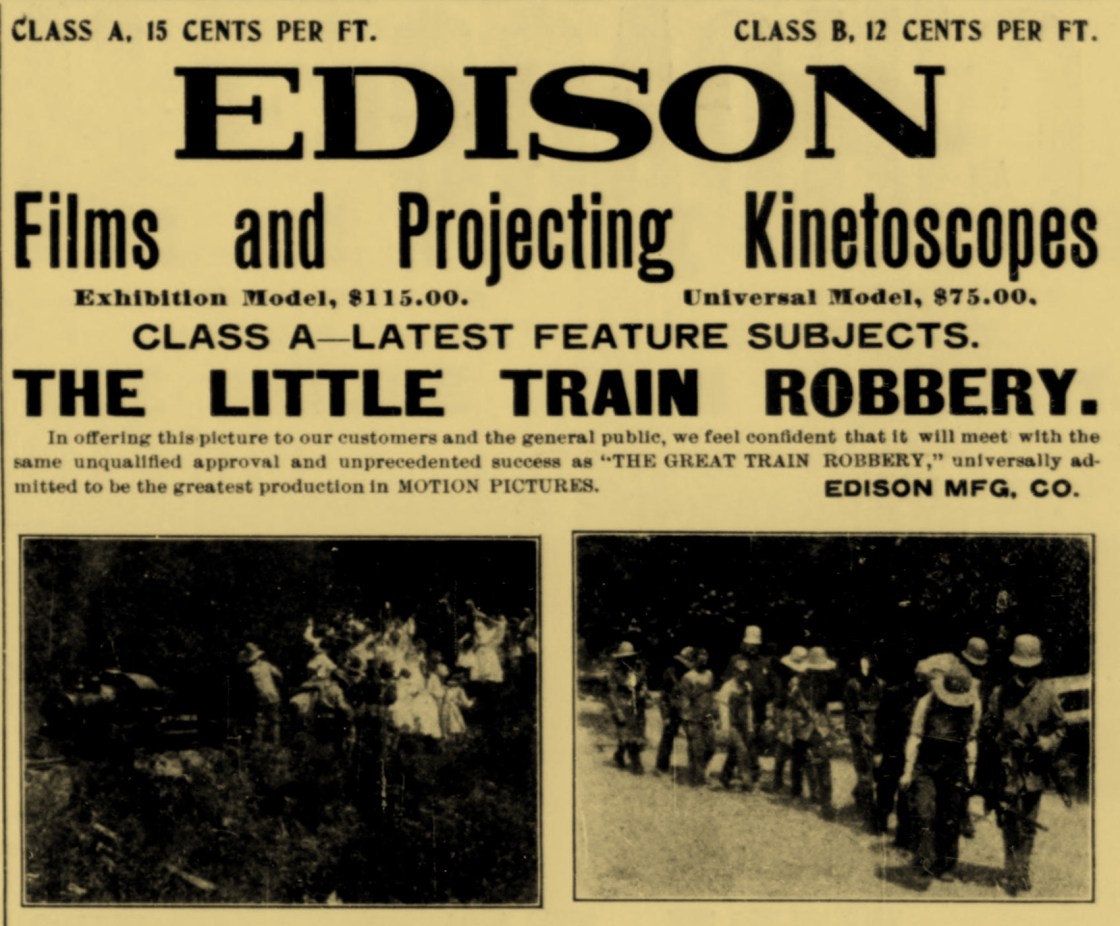

I am fascinated by the Class B-Latest Featured subjects for sale.

“FATAL NECKLACE?”

“ECCENTRIC BURGLARY?”

“RACE FOR BED?!?”

Tell me more, Edison Manufacturing Company.

Yes, always these tantalizing hints

Thank you for your review-I’ll watch it today via The Library of Congress link. I like Our Gang and how the kids use their imagination, and will be curious to see what this group of children do!

Yes, it’s very cute!