Helen Keller joined celebrities like Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb in portraying herself in the story of her own life and the resulting movie is a push-pull between Keller’s socialism and her desire to create a more symbolic picture and the producers wanting a commercial smash.

Home Media Availability: Available for free streaming.

I’m also covering the 1962 Keller biopic The Miracle Worker. Click here to skip to the talkie.

When the Saints Come Marching In…

It’s likely that many of you will already be familiar with Helen Keller but just in case, here is a very brief rundown of how she is portrayed in pop culture. Born in Alabama in 1880, Keller was rendered deaf and blind by an illness. Exceptionally bright but allowed to run wild by parents who mistook indulgence for love, Keller was just shy of seven years old when she was taught the manual alphabet by her teacher, Anne Sullivan. The breakthrough word, water, led to thousands more and Keller become a prominent advocate for the blind.

And this is usually where the story ends. Like many Americans, I was assigned Keller’s autobiography, The Story of My Life, in grade school and enjoyed it very much. It was only when I reached adulthood that I learned that there was so much more to Keller’s life.

Now, there’s obviously nothing wrong with portraying Helen Keller’s childhood. However, there is a definite peril in only portraying her childhood, keeping her safely encased in amber as a small child and conveniently segregated from the political and social views that would define her adulthood.

As humans, we have a tendency to deify our heroes and while there is nothing wrong with admiring good qualities, brave stands and smart writing, turning people into saints naturally results in dehumanizing them and making those very qualities and accomplishments seem out of reach for mere mortals.

Keller was gracious, her writing is witty and perceptive but she was not a serene saint. Her political views were as radical then as they seem today: she was an ardent socialist and member of the IWW, she helped found the ACLU, she held pacifist beliefs and strongly opposed the First World War, and, alas, she embraced then-trendy eugenics.

In short, we are dealing with a complicated woman with a complicated legacy. It’s no wonder that the pop culture portrayals have kept her at six years old.

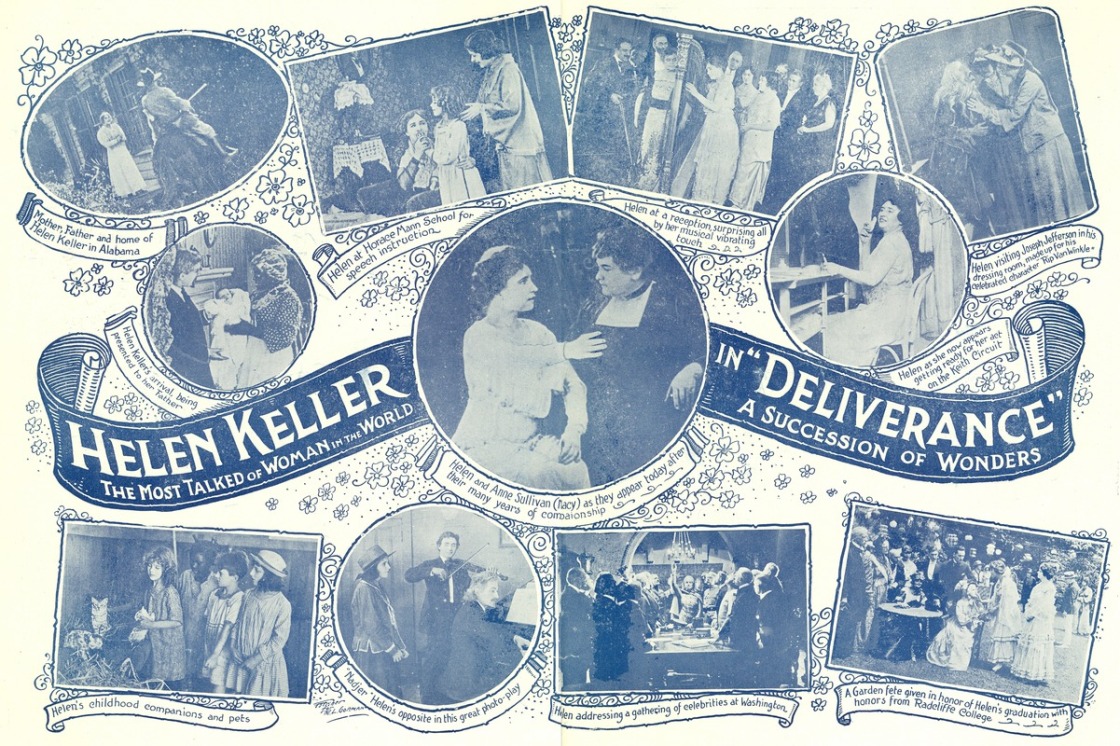

But before The Miracle Worker, there was Deliverance. Helen Keller had contractual creative control and portrayed herself in the final reel of the picture. How would the woman herself choose to present her life and philosophy and was she able to share her controversial beliefs? Well, as you can see, Deliverance survives and so we can find that out for ourselves.

The film is divided into three parts: first we are shown Helen’s childhood and then her young womanhood as a student and then we see her in the present day. Etna Ross was the child Helen, Ann Mason played her as a young woman and present day Helen was portrayed by herself.

The childhood section is familiar territory: Helen is pampered and indulged and allowed to run roughshod over everyone, including Martha Washington (Jenny Lind), the daughter of the family’s cook. Keller later wrote that she and Martha had devised signs and she never had trouble conveying what she wanted to the other child. Unfortunately, the film opts for a rather stereotypical portrayal of Martha, using her for broad comedy relief. At least one version of the film’s credits lists the character as “Pickaninny Martha Washington.”

(In general, Martha is ignored when Keller’s life is discussed. Equally ignored is the fact that just a few years before, Martha and her family would have been the property of the Kellers, which make the “charming” anecdotes of Helen dominating Martha considerably less pleasant.)

Little Helen’s world changes the moment Anne Sullivan enters her life, introduces discipline and teaches her how to spell the names of the various objects around her. We get the magical moment at the pump when Helen realizes that the letters spelled into her hand W-A-T-E-R mean “water” and that she is no longer isolated from the rest of the world. From there, Helen is able to attend school and her keen mind more than makes up for lost time. In the meantime, the film also shows Helen’s inner world as she imagines herself into Ulysses.

Throughout the picture, the audience is also shown Nadja (Tula Belle in the childhood sections), a peer of Helen’s who is jealous of her as a child but then goes her own way in life, drops out of school, marries, is widowed and eventually sends her son off to war. This gives the picture an opportunity to show Helen’s willingness to help the blind.

The mantle of saint can be burdensome to the person wearing it. I was quite curious to see how the politics of Helen Keller would mix with those of producer George Kleine, who was conservative, starchy and a fellow traveler with Henry Ford. The answer was: not very well.

Keller dedicated an entire chapter to the production of Deliverance in her book Midstream: My Later Life. She expresses regret that the picture lost money for the producers but describes a production with a runaway budget and too many cooks in the kitchen.

Keller had hoped that the film would be less biographical and more symbolic of her inner world and I agree that this approach would have had merit. Alas, producer and director George Foster Platt opted instead for a hybrid approach with a few fantasy sequences but most of the picture dealing with the famous events of Keller’s life. A dreamy, surreal film would not have been out of step with the tastes of the day. Directors like Marshall Neilan and Victor Fleming were accomplishing just that with big stars like Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks.

In her book, Keller describes numerous scenes that are not present in the cut that I saw. There was to be a sequence in which Knowledge (played by a young lady) and Ignorance (played by a strapping man) would duke it out for supremacy. There was to be a scene in which Keller tells off the architects of the First World War, J’Accuse-style.

By the way, thee extant Jesus sequence introduced Keller to the concept of a Hollywood stage mother and she wrote that she hoped the director would write his memoirs and share his opinion of “members of the human species who sell their children to producers for three dollars a day.” Oh snap!

Keller stated that everyone had their own ideas and it sounded a bit like everything was made up as the picture was filmed, which would explain why so much material was left on the cutting room floor. If that was the case—and Keller is so frank about her inexperience and discomfort that I see no reason to disbelieve her—then it certainly would be a wasteful way to film and it’s no wonder that the picture lost money.

A major concern for the producers throughout the picture was a lack of love interest for Keller, thus there is scene in which she imagines herself as Circe seducing a mythical man. Oh my! But for the most part, I believe the producers underestimated the interest that could have been generated by showing the education process. The scene in which Keller re-learns speech is far more honest and interesting than a dozen invented classmates.

The Nadja story is a definite weak link in the picture and Keller used her authority to request its removal. It remains in the print that I viewed but was apparently eliminated in cuts of the picture distributed to the educational market.

Keller was quite correct about the Nadja storyline. Given the differences in their circumstances and the societal disadvantages Nadja faced as an immigrant without a father in 1880s America, it seems pointless and cruel to constantly trot her out in comparison to the relatively privileged Keller.

In Daddy Long Legs, Mary Pickford’s orphan character is given a rival in the form of Fay Lemport, who plays the spoiled daughter of one of the orphanage trustees. This works because Lemport’s character has money, beauty and indulgent parents and her future is secure no matter what. This positions Pickford’s character as the underdog and the rivalry is helped along by the rich child’s bratty behavior.

Nadja, meanwhile, is guilty of nothing more than not wanting to share her childhood crush with Helen and opting not to stay in school after the teacher loudly compares her unfavorably to her rival. I have a hard time holding childhood behavior of this type against the adult version of the character.

When Nadja’s son returns from the war blind, the audience was clearly supposed to experience some kind of emotional moment when the erstwhile rival of Helen Keller asks her for help. But, really, the girls hadn’t interacted since about the first grade. I wouldn’t mind seeing my first grade pals again (Hi, Crystal, if you’re out there!) but the connection between Nadja and Helen is so tenuous that the drama is weak.

If Nadja had made prejudiced anti-blind statements or experienced an emotion beyond minor childhood jealousy, perhaps the rivalry would have worked better. But “the kid who kind of didn’t like you when you were six” doesn’t exactly work in the arch-rival department.

The Nadja storyline was clearly intended to inject melodrama and satisfy Keller’s demand that the film include scenes of WWI soldiers blinded in the conflict. It’s a rather poor substitute and would be even if it wasn’t dramatically inert. A single actor playing a blind soldier for a minute or two of screentime is not the same as showing dozens, hundreds of young men who lost their sight in a war that Keller did not support.

Worse, the title cards have the characters deliver bland statements of patriotism, which didn’t match Keller’s own beliefs and which would have seemed dated in 1919. We’re informed that the soldiers sacrificed themselves defending… something, reality be damned.

Keller was also uncomfortable with the finale of the picture, which featured her riding a horse, blowing a bugle and leading veterans to… something. Again, this is a case of the filmmakers shying away from the real political opinions that Keller held. Socialism, guys, she was leading them to socialism. (Keller walked the walk too. She refused to attend the premiere of her own picture because it would have meant crossing a picket line.)

In the end, Keller found Vaudeville much more to her taste and the Helen Keller Film Corporation quietly folded. And while it’s true that Deliverance is not exactly a good motion picture, it does give us insight into Keller’s beliefs and opinions, even if she did not enjoy the creative control to which she was entitled. Seeing the film in conjunction with reading Midstream tells us a lot about Keller, the state of American pictures in 1919 and how even the best intentions can go awry.

Certain scenes of the film do work. The childhood sequences with Anne Sullivan do an excellent job of conveying the frustration and joy of Helen learning to communicate. And while Keller herself stated that she was no actress, it’s still fun to see her in the flesh.

I wouldn’t recommend this picture for a casual silent film fan or someone who has no interest in Helen Keller. The picture lacks focus and anything resembling forward movement and the fictionalized elements clash with the biographical material. While the fantasy sequences are interesting, they are too few and far between to really change the tone of the picture.

However, anyone who has read about Keller’s life and experiences will likely want to check this picture out. Reading Midstream alongside it is essential if you want to extract every ounce of information. Enjoy!

Where can I see it?

Available for free and legal viewing on the Library of Congress’s official YouTube channel with a fine score by Stephen Horne.

Silents vs. Talkies: Deliverance vs. The Miracle Worker

While Helen Keller’s early autobiography remains popular, I dare say that most modern people first encountered her in some version of The Miracle Worker. Instead of hiring big Hollywood names, the 1962 film version of the play imported its leading ladies from the stage, Patty Duke and Anne Bancroft, and the perceived gamble payed off with Academy award wins for both women.

We know the story by now and The Miracle Worker is based on The Story of My Life, so let’s dive right in.

Okay, I’m going to start this off with a simple statement: nobody had better EVER AGAIN try to tell me that silent films are more melodramatic than talkies. Now mind you, I don’t think there’s really any tour de force acting in Deliverance but at least the cast doesn’t spend the entire film shrieking and throwing themselves about. And no, I am not talking about Duke’s Helen.

I have to confess that I was somewhat soured on the film from the opening scene in which Helen’s parents (Inga Swenson and Victor Jory) discover that their daughter is deaf and blind. Mom just starts screaming bloody murder, as though she discovered a succubus in the cradle. I can understand tears and being upset given the limitations society placed on blind and deaf people at the time but the overblown reaction strikes me as pretty insulting. (I never thought I would favorably compare Mr. Holland’s Opus to anything but the discovery of the deafness of a musician’s child was handled with far more grace.)

From there, it’s a battle of wills between Helen and Anne Sullivan but since Patty Duke was a teenager when the film was made, the dynamic is considerably different from reality. When a six-year-old child throws a tantrum and hits and kicks, there’s a limit to how much damage they can do to a fit adult woman. When a fifteen-year-old throws the same tantrum, the danger increases considerably. This isn’t necessarily a dealbreaker for me but it does make the indulgent behavior of Helen’s family far more inexplicable and bizarre.

Martha Washington is completely eliminated from the narrative save a small scene at the beginning in which Helen tries to hack off her hair. This is also a pity because she was the first person to make any kind of communication breakthrough with Helen. I realize the story is all about Anne the miracle worker but it’s a shame to see it at the expense of Martha.

I thought Victor Jory was quite good as the blustering patriarch who is all bark and no bite, though the “cute” Confederate apologia that the character spouts is tedious in the extreme. And it’s not that Duke and Bancroft don’t have good moments, I just wish the whole thing had been handled with the screen in mind instead of the stage.

This picture reminds me of the stage stars and properties that tried their hand at the silent screen but couldn’t get that balance right, you see. Stage plays require a broader performance and allowances for the fact that closeups do not exist. Director Arthur Penn has everyone’s performances cranked to eleven and while I understand that he was going for a particular acting flavor (a similar one later used in Bonnie and Clyde) but it’s not to my taste, not one little bit.

That’s not to say there are no cinematic moments in the picture. There are artistic double exposures and flashbacks and dream sequences, don’t get me wrong, but a film made in 1962 couldn’t figure out how to convey finger spelling without the characters announcing what they were doing while a film made in 1919 did the same trick easily. Color me unimpressed.

And the winner is…

The Silent

Trust me, disliking this talkie was not on my bingo card either. I have to admit that I was surprised and annoyed by how unmoved I was by The Miracle Worker and I know I’m in the minority but, well, this is a review and a reviewer has to share their opinion. And mine is that the film does a far poorer job of conveying Keller’s state of mind than Deliverance.

Deliverance is a classic example of too many cooks spoiling the broth but The Miracle Worker seems to be suffering from a severe case of playing to the cheap seats. Nobody simply reacts, everyone has to scream and holler and carry on. Rather than take advantage of the grammar of cinema and convey the miracle of understanding, the film contents itself with smacking the audience over the head repeatedly.

Many viewers and the Academy disagree with me but that’s the way it crumbles, cookie-wise. Deliverance manages to eke out a narrow and not entirely noble victory.

Availability: Released on DVD and Bluray.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Very interesting. I will definitely make some time to watch DELIVERANCE.

I have watched THE MIRACLE WORKER many, many times of the years, and although I most probably like it more than you do, I have always found the mother’s reaction a wee bit over-the-top. Many parts of the film do appear stagy but I still love the scenes with Patty Duke and Anne Bancroft and think that Duke was marvelous.

As an aside, in the recent past years I became more aware of Victor Jory in films from the 1930s and when I see him, I always refer to the fact that this is the film that first introduced me to him way back when.

Thanks for the enjoyable read!

Thank you!

Hey Fritzi! Interesting to find out more about it. I had quite a few questions after watching it and you covered ‘em all (and then some!). 😁 Thank you!

P.S. I love the line, “as though she discovered a succubus in the cradle”. Lol!! That one’ll stay with me in future viewings of The Miracle Worker!

My pleasure!

I didn’t know Deliverance existed, so thank you. Keller’s awareness of the film’s defects (and of stage mothers) is all the more interesting since she was dependent on having the experience , both on the set and watching the film, signed to her. This is not to diminish her brilliance, but to note that her world was necessarily filtered through another’s perceptions except when she was reading.

In fairness to Keller, quite a bit of what she discussed was the sort of information she could have accessed through direct communication. Box office receipts, for example.