Winsor McCay returns to the world of the Rarebit Fiend, with a man overindulging in cheese toast and dreaming that his wife takes in an unusual pet that grows, and grows, and grows…

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Stomp Stomp

Winsor McCay was the mind behind popular strips like Little Nemo in Slumberland and Dream of the Rarebit Fiend and he was among the earliest pioneers of popular animation in the movies. McCay adapted the latter series to the screen once again in 1921, promising a one-reel animated short every month for twelve months. The first was Bug Vaudeville and The Pet followed.

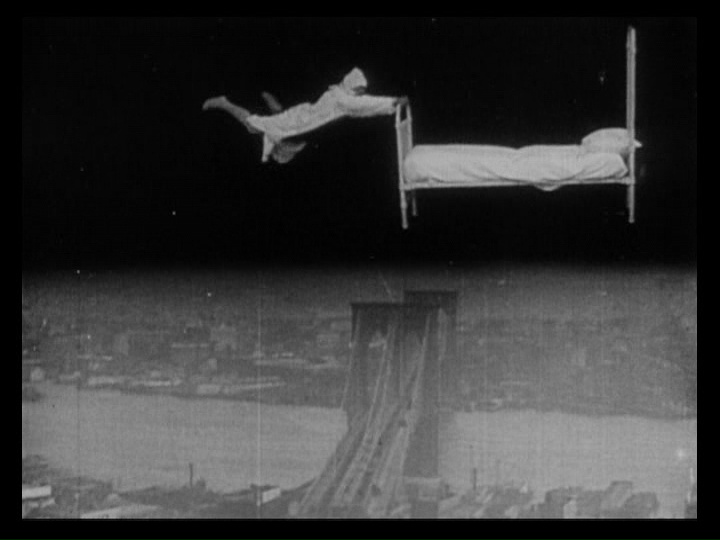

McCay’s strip had previously been adapted by Edwin S. Porter of the Edison company as Dream of a Rarebit Fiend in 1906 and, despite being live-action, that film was extraordinarily faithful to McCay’s original artwork. However, there are limits to what the human body can achieve, even with cutting edge effects, and McCay took full advantage of animation for his 1920s attempts.

The Pet opens with a married couple in bed together (scandal!). Col. B says that he indulged in rarebit at the club and Mrs. B replies that he knows what odd dreams it causes. Rarebit was toast with a cheese-mustard-beer mixture of varying degrees of sauciness. It could be broiled but a huge part of its appeal in late-19th and early 20th-century America was the fact that it could be prepared in a chafing dish without having to set foot in the kitchen. The chafing dish was viewed the way a barbecue is today: an acceptably masculine way for a man to cook. And rarebit could be made with cabinet ingredients, should the cook have a night off.

However, mustard and beer and cheese were seen as a spicy combination and McCay built on this reputation to imagine a nightmarish world within the cheese toast-primed subconscious. (Porter also made sure to show the fiend indulging in multiple bottles of beer alongside his meal.)

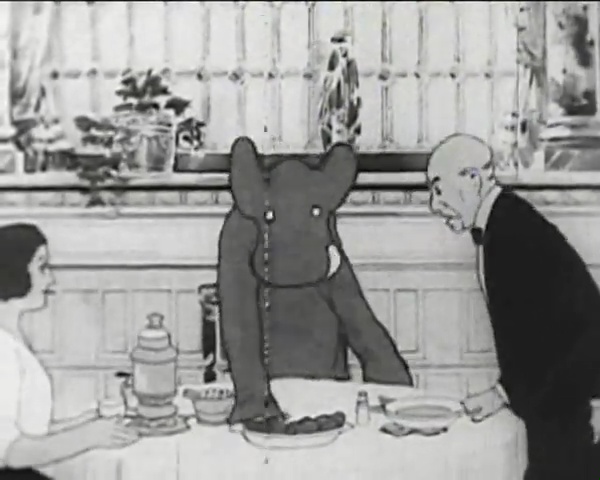

So, Col. B dreams that Mrs. B takes in a curious little creature, a sort of meowing tapir. She fusses over the thing and names it “Cutey” after her husband. Col. B is not amused, especially when the now-beagle-size creature kicks him out of his own bed. By morning, Cutey has grown to the size of a labrador and, after observing carefully to make sure Col. and Mrs. B aren’t watching, eats the family cat whole.

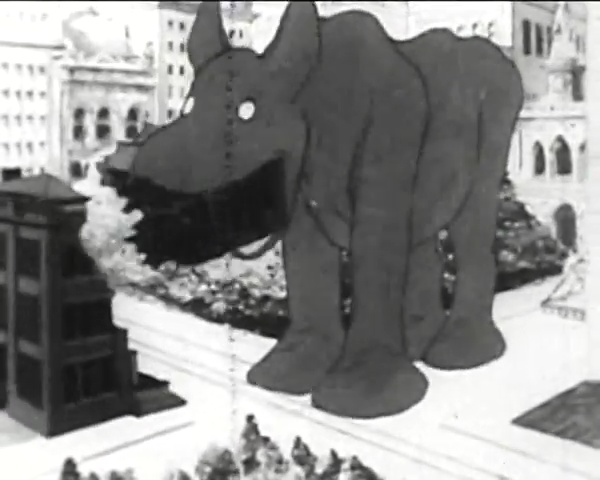

Col. B starts to becomes alarmed and heads to town to purchase poison for Cutey. Meanwhile, Cutey is rampaging through the house, eating furniture and growing ever larger. It eats an entire barrel of rat poison delivered by Col. B but only seems to grow stronger. Cutey eats its way out of the walled garden and heads into town, where it reaches gargantuan proportions and begins to eat entire buildings. Airplanes and zeppelins bomb Cutey and there is a huge explosion and… well, Col. B was warned about the rarebit, wasn’t he?

The Pet displays McCay’s signature bold compositions and strong grasp of perspective, he was most responsible for the artistry of early film animation, in my opinion. The Pet doesn’t break the fourth wall the way Bug Vaudeville did but its escalating frenzied tone and dream logic are delightfully bizarre and show growth beyond the “look, ma, we’re animated!” early days.

While I generally have a very high opinion of this film, the poison-buying scene is a good example of McCay struggling to use animation to convey what would be easily shown in a single comic strip panel. Col. B states his trouble, the shopkeeper suggests the poison, Col. B orders a barrel of it. Three title cards in the space of a few seconds. A more visual solution would have been to have Col. B pantomiming Cutey’s behavior, the shopkeeper pointing to the poison brand name and then including a title card with Col. B placing his order. If we wanted to be even more visual, Col. B could reject smaller packets before accepting the barrel.

These bugs were fairly common when an artist from a different medium was attempting to make a silent movie. For example, the 1916 version of Sherlock Holmes constantly betrays its stage origins and fails to capitalize on the advantages of cinema. I am sure McCay would have smoothed out the rough bits if he had been able to continue in animation.

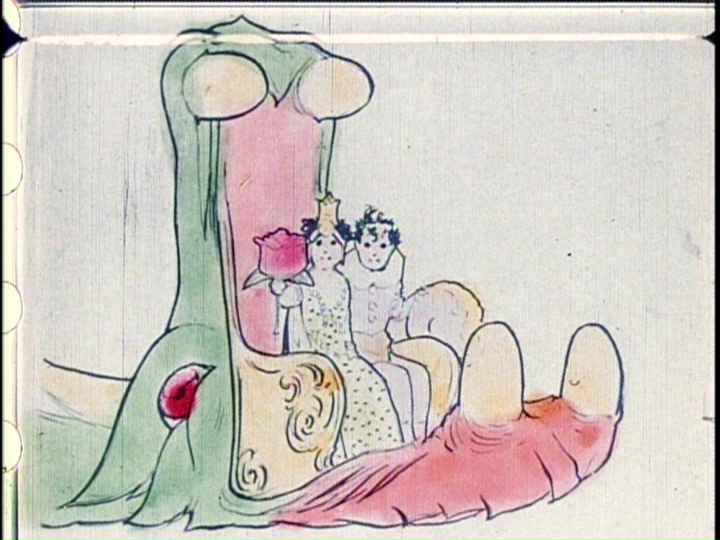

McCay had veered into dark themes (like the sinking of the Lusitania) and black humor before, creating an illusion of an audience member being eaten by a spider in Bug Vaudeville, and he was fascinated by the gigantic in both biology and fantasy. McCay had toured with his Gertie the Dinosaur animation, which allowed him to interact with a massive animated brontosaurus projected on the screen. His Little Nemo series had featured a dragon chariot, an enormous creature that opens its mouth to reveal a tongue shaped like a pair of thrones. These were benevolent beings, though, and Cutey is decidedly not. What’s more, it takes pleasure in its path of destruction.

Prehistoric themes were wildly popular (I theorize it was at least in part due to the convenient excuse for skimpy fur costumes) and dinosaurs were a reasonably common sight in the movies, with Willis O’Brien hard at work with releases like The Dinosaur and the Missing Link: A Prehistoric Tragedy (1915) and R.F.D. 10,000 B.C. (1917), fully stop-motion animated caveman adventures, the latter complete with dinosaur mail delivery truck. O’Brien also combined live-action with animated dinosaurs for The Ghost of Slumber Mountain (1918). However, these dinosaurs were either in a prehistoric or wilderness context.

McCay had brought the dinosaur to the city with Gertie and Arthur Conan Doyle had written of an escaped pterodactyl causing chaos in modern London in his novel The Lost World (1912). (And, of course, O’Brien provided the effects for the 1925 film adaptation, with a bronto subbed in as the rampaging dinosaur.)

The Pet brings in fantastical giant creature and sets it loose in a modern city as the army attempts to destroy it with every weapon at their disposal a decade before King Kong. (I am cautious about declaring firsts in silent film but it’s certainly the earliest I have seen.) Kong, along with The Lost World, created building blocks for giant creature features and kaiju films as we know them. While I wouldn’t say that The Pet should take their place in the city rampage creature feature timeline, it was made earlier and is remarkably complete in its city stomping tropes.

Also, McCay gives Cutey a naughty personality. This isn’t a stressed beast climbing the Empire State Building or trying to return to its island home. We are never shown where Cutey came from, and it doesn’t really matter as this is a dream with dream logic, but it displays knowledge and pre-planning in its antics. It looks around carefully to see if it is being observed before swallowing the cat whole, it points the garden hose at the husband and gives him a spritz. Cutey would fit seamlessly into the 1960s and 1970s Godzilla series entries.

The “what could go wrong?” beginnings, the rapid growth, the smashing of walls and buildings, the final military assault to destroy the beast, it’s all there and delivered in a remarkably efficient package. I would say The Pet is probably more of a detour that a precursor in the history of giant creature rampage/kaiju but it should be included in the conversation. Also, Cutey’s monstrous behavior being linked to food makes it something of a distant relative to Gremlins. And it’s fun!

McCay had been in the animation game since the early 1910s and even boldly advertised that he had invented the art but the movie landscape of the 1920s was very different from where he had come in. The studio system had taken hold, movies were bigger, a one-man production and distribution outfit was possible (Oscar Micheaux was doing it) but it was enormously challenging. Further McCay had a contract with Hearst newspapers and was refused a leave of absence to pursue his animation endeavors.

The Flying House followed The Pet in the revived Rarebit series but the animation was credited to McCay’s son Bob. The other nine promised films in the series never materialized, so all we have left are whispers of what might have been.

The Pet is quite something. Come for McCay and stay for an early example of a rampaging beast with all the trimmings.

Where can I see it?

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.