This film was labeled “too gruesome for real enjoyment” by one reviewer when it was released. Not for ladies. Just too much. Sounds great! It’s a bloody Hobart Bosworth ship melodrama with death and vengeance on the high seas.

Home Media Availability: Released on Bluray.

No Girls Allowed

While there have been plenty of talkies about murder and revenge on the high seas, I think that the silent era just did it better. Maybe it was the closer proximity to Victorian grimness. Maybe it was because some silent movie personnel had actually been to sea. For whatever reason, if you want dark and deadly nautical fare, the silents are where it’s at.

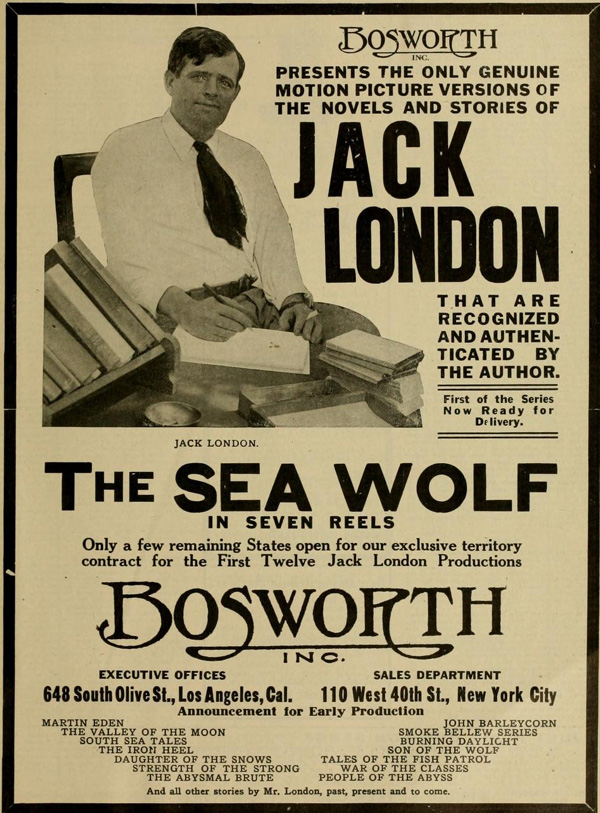

The genre’s durability was a known fact during the era and was a smart strategic choice for newer companies. Early film star Hobart Bosworth’s company made a deal with Jack London and produced a whopping seven-reel adaptation of The Sea Wolf in 1913 with Bosworth in the title role. The company sold to Paramount but Bosworth kept up his violent nautical ways. The infamously violent Behind the Door (1919) and the quieter but creepier Below the Surface (1920) have recently enjoyed a new release and we can also see Bosworth doing what he did best in The Sea Lion (1921). Alas, The Sea Wolf is missing and presumed lost.

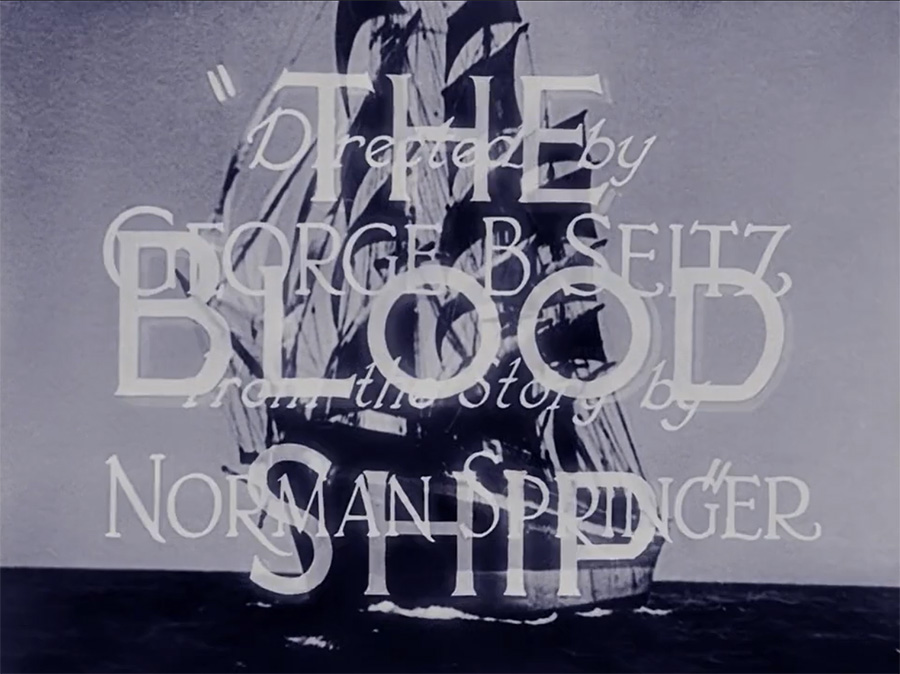

The Blood Ship, a vehicle built around Bosworth’s unique talents, was Columbia’s way of announcing its arrival as a major studio in 1927. Just as Fox had done with A Tale of Two Cities in 1917, Columbia wanted something big and bold and splashy to show that it wasn’t just another minor player, it could rival any of the more established companies. It worked, Columbia thrived but The Blood Ship was forgotten.

I have been eager to see this picture for going on 15 years and was delighted to see that it finally had been released on Bluray last year. I know that there is always a risk when a movie has been built up in my own mind for so long but I am never able to resist Bosworth shivering his timbers.

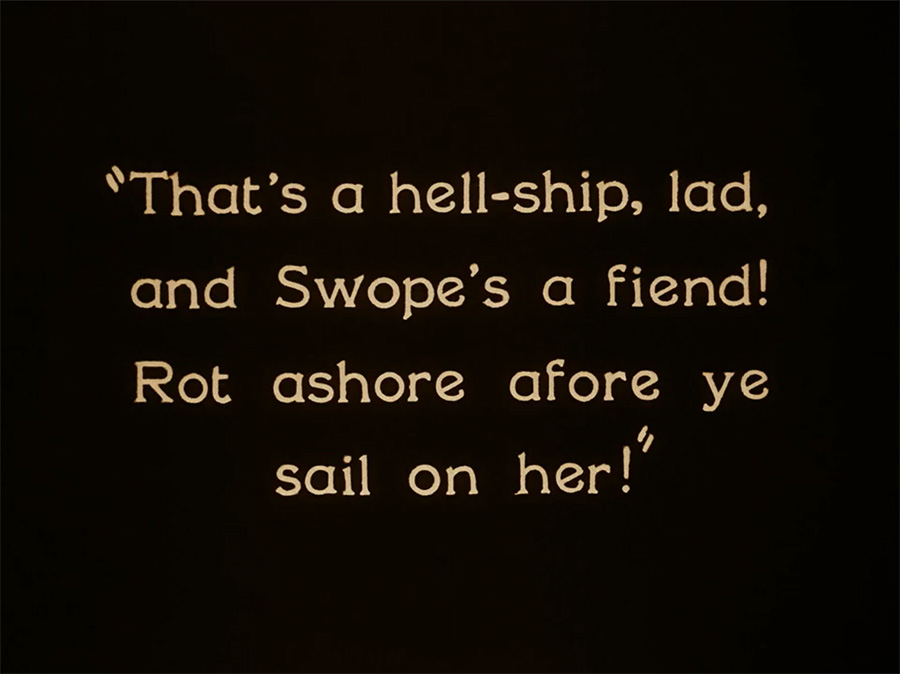

The picture opens on the Golden Bough, the blood ship of the title, a merchant vessel that is ruled by the sadistic Captain Angus Swope (Walter James) and his equally horrible first mate Fitz (Fred Kohler). Swope’s daughter Mary (Jacqueline Logan) is horrified by the brutality meted out on the sailors and plans to escape ashore in San Francisco. No sailor is going to sign on for a second cruise and the ship’s reputation precedes her, so the Golden Bough will be docked for a time to recruit (or kidnap) a new crew.

Ashore in San Francisco, a sailor named John Shreve (Richard Arlen) is drinking in a saloon owned by the Knitting Swede (James Bradbury Sr.), a Swedish man who, well, knits and helps Swope keep his ship manned. Shreve butts heads with the saloon’s Cockney bouncer (Syd Crossley) and meets a mysterious, glowering older man named Newman (Hobart Bosworth). Shreve beats the bouncer in a fight, backed by Newman, who is quite the tough cookie.

Mary manages to get ashore in San Franciso and runs into Shreve, who falls in love with her at first sight and ruins her getaway with awkward, handsy flirting. Swope drags her back aboard the Golden Bought and, realizing where she has gone, Shreve jumps at the chance to sign on as a sailor on the ship, much to everyone’s surprise as nobody joins that crew willingly. Newman also volunteers and the Knitting Swede, deciding that his beaten bouncer is no longer an asset, sets him up to be shanghaied as well.

Other significant members of the new crew include Rev. Deakon (Chappell Dossett), a do-good preacher who was threatening the Knitting Swede’s business with his ministry, and a character only described as “Negro” in the credits, played by baseball star-turned-actor Blue Washington. (I’ll refer to him as Washington for the duration of the synopsis.) Washington just wanted to make his way quietly through San Francisco and not make trouble or find trouble, so he is inclined to keep his head down for the duration of the cruise. Deakon, however, is outraged and demands that Captain Swope put him back ashore. He is beaten for his trouble and the crew quickly quiets down.

Newman, who has been keeping a low profile, sneaks into the captain’s quarters and confronts Swope. We learn the truth about Mary: Swope framed Newman for murder and, while he is in prison, abducted his wife and daughter. Newman attacks Swope but is distracted when Mary emerges, having overheard the confrontation. Swope orders her outside and acknowledges that she is Newman’s missing daughter but tells him that she would be ashamed to know a convict is her real father. Newman is stunned and leaves.

Meanwhile, Mary and Shreve begin to flirt (scenes very similar to the romantic moments in Old Ironsides) and a romance blooms. Mary is also connecting with Newman, which angers Swope. He takes it out on the youngest member of the crew, just a boy really, and beats him half to death. The rest of the crew was fond of him and tries to tend to his injuries but Fitz forces them out and back to work. The boy dies alone.

Washington takes the death particularly hard and vows that he will kill Fitz. Newman doesn’t speak but it is clear that he feels the same way. This is all part of Swope’s plan. At the boy’s funeral, he arrests Newman, hoping that he will resist and can be shot in the back by a concealed Fitz. Mary warns Newman in time and he is taken below by Swope, who was earlier shown fashioning a brand new cat o’ nine tails…

This all sends the cast hurtling toward the grand finale, which we will be discussing, but suffice to say for now that the movie lives up to the title.

First, to be clear, there is nothing in The Blood Ship that we haven’t seen before. It is very much a movie constructed of borrowed parts: a dab of The Sea Lion, a touch of Behind the Door, a dollop of Old Ironsides. Reviews also mention that it resembles The Sea Wolf (1913), which makes me even more eager to watch that picture, if it’s ever found. Derivative as it is, The Blood Ship still works because, for the most part, the filmmakers selected choice bits with a clear goal in mind. They weren’t just copying popular elements willy-nilly but were instead trying to reverse engineer the ultimate nautical revenge picture with the best ingredients from everything else.

Sometimes, doing a new thing is overrated and being able to produce a variation on classic themes very, very well is enough and that is the case with this film. Everyone involved knew what they were doing and did it. The villains are nefarious, the heroes are shabby and bloodstained but worthy of cheering, the cinematography (credit to Harry Davis and J.O. Taylor) is suitably moody and serial veteran George B. Seitz keeps things moving so fast that the glued-together seams don’t show.

Despite ostensibly being the hero of the picture, borrowed from Paramount for the purpose, Richard Arlen is given surprisingly little to do in the picture once the Golden Bough puts out to sea. He romances Jacqueline Logan, of course, but all of the resistance against Captain Swope is handled by Deakon, Washington and, of course, Newman. I did like Logan’s character, who is imperiled but not really a damsel, but Arlen felt superfluous.

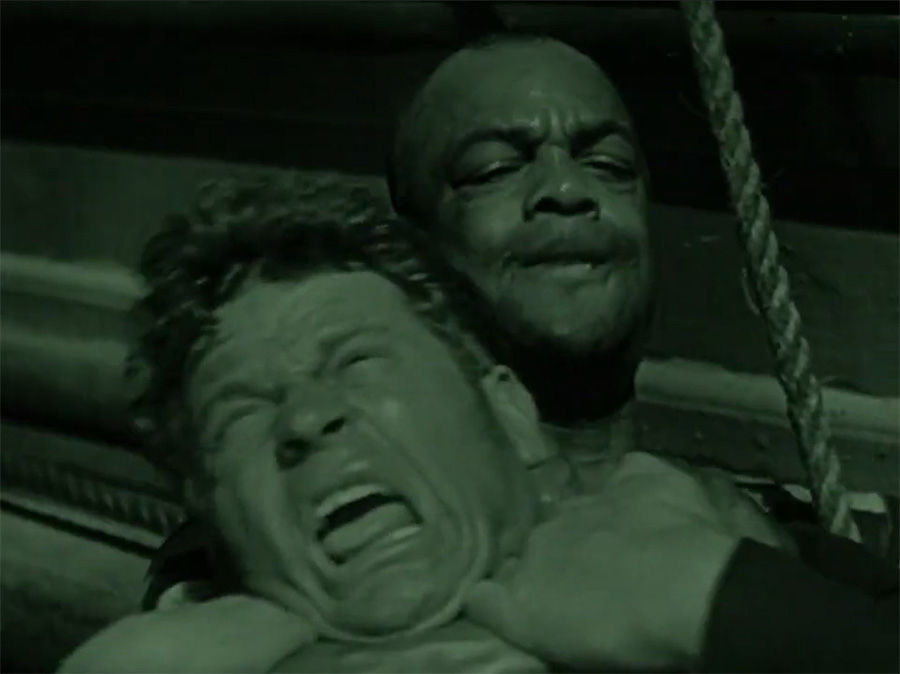

While Blue Washington is given stereotypical dialect title cards and not even granted a proper name or nickname (at least the Knitting Swede was knitting), the film essentially treats him and not Arlen as the second male lead after Bosworth. Washington is the one who experiences character growth, going from “keep my head down and survive” to leading the charge, backing Newman, coming to Mary’s rescue and defeating Fitz single-handed in the grand finale, sparking a general mutiny.

Reviews of the period describe his character as comedy relief with no further details. While he has some comedy relief moments, the type typically given to Black actors during this highly segregated era, Washington is also quite a heroic character when the chips are down. Shreve starts the film as a standup guy and remains one but he is surprisingly passive during the finale, with most of the action in support of Newman handled by Washington and Mary.

Washington’s character is not flawless representation (the movie ends with a blackface gag, for heaven’s sake) but I was pleasantly surprised by how much the screenplay gave him to do and didn’t force him to pay for his heroism with his life. Washington makes the most of the opportunity and the beautiful closeups, impressively conveying his character’s fury and, later, joy.

Of course, we’re all here to see Bosworth make the decks run red. He is introduced in style, a silent and menacing figure of mystery, but grows passive once his past is revealed aboard the Golden Bough. In fact, he stays stubbornly passive throughout most of the picture, even as he is arrested by Swope. I was a bit worried that The Blood Ship would end with a fizzle (keeping in mind that Bosworth taxidermied that last guy who messed with his cinematic wife) but things rapidly pick up again at the film’s final stretch.

Swope flogs Newman and boasts about how Mary’s mother died. Newman is furious but helpless. However, Mary overhears everything. Fitz is about to attack her but he is grabbed from behind by Washington, who throttles him and throws him overboard, triggering a general mutiny. Swope rushes out to battle the mutineers and Mary goes below to free her father.

With Swope shooting down the crew and injuring Washington, things look dire but Newman grabs the captain’s cat o’ nine tails and confronts him, beating him. The ferocity of the scene is enhanced by cuts, dramatic lighting and tracking shots. Dead, alive, who cares, Newman throws Swope overboard and strikes a crucifixion pose.

Now that is what I am talking about!

The film was adapted from the novel of the same name by Norman Springer and makes several significant changes to its source material. The first may have been either a bow to censorship or to Bosworth’s age or both: in the novel, the heroine was married to Captain Swope and marries Newman quite literally over her husband’s dead body at the end. Making her Newman’s daughter takes a few beats from The Sea Lion. She ended up in Swope’s custody when he abducted her mother, scenes clearly inspired by Behind the Door.

The book opens with a frame story (forgotten by the final chapter) of an elderly Shreve recalling the happenings on the Golden Bough for a pesky author. This always removes some suspense from a tale like The Blood Ship— Shreve is going to survive no matter what, so his moments of peril hold little spark or suspense. The movie throws us right into the action with young Shreve, no framing and no assurances of survival. (Although handsome leading men in Hollywood productions usually did have plot armor as a rule.)

Finally, the character eventually played by Blue Washington in the film was a villain. Like his film counterpart, he was never given a name in the book but was rather referred to by a very offensive slur throughout the story before being killed with the other villains. This was all reversed and cut from the story, with the character being turned into a hero and slurs cut entirely. This change was possibly inspired by boxer George Godfrey as a heroic figure in Old Ironsides and it’s not perfect but it’s an improvement. Granted, the bar for films of the period was so low that it was practically inside the earth’s core…

So, all in all, Fred Myton’s adaptation of the book elevated the material with choice bits borrowed from earlier hits. This has always been a popular method in screenwriting. (Frances Marion’s adaptation of The Wind lifted whole scenes from the similarly-themed drama The Canadian, for example.)

Reviews of the time fell into two camps: enthusiastic raves and queasy warnings that perhaps this film went a bit too far. Fan magazine Photoplay fell into the latter category: “A real he-man picture and this is one time we feel the ladies will like to be excused. A picture that is well produced and directed; filled with splendid performances; but its story is one of mutiny, brutality, murder and a girl. Too gruesome for real enjoyment. Hobart Bosworth, Jacqueline Logan and Richard Arlen are in the cast, with Bosworth giving one of the finest performances of the month.”

The trade press, on the other hand, fell over itself praising the picture, breathlessly recounting packed theaters, standing room only, enthusiastic applause and box office appeal. Two lengthy op-eds in Motion Picture News declared that The Blood Ship was a powerful argument against both block booking and films-by-committee that were becoming the standard in the still-relatively-new studio system. The film was booked at the prestigious Roxy theater for its premiere and was the talk of the industry.

For all its splashiness, The Blood Ship had the misfortune of being released in the summer of 1927, just before The Jazz Singer would turn the movies on their head. The Blood Ship was an excellent silent movie but it didn’t have legs as long as other hits of the era because of its unfortunate release date. In fact, Columbia remade it just four years later as Shanghaied Love, directed by Seitz again and with Noah Beery, Richard Cromwell and Sally Blaine as Swope and the romantic duo, Willard Robertson in the Bosworth role and Fred “Snowflake” Toones in the Washington role, the character renamed Snowflake to match. (One step forward, two steps back.)

I wasn’t able to obtain a copy of this remake for review but from the AFI synopsis and a capsule reviews in Photoplay and Silver Screen, it sounds like a plodding, chatterbox affair that talked when it should have punched. Both reviews specifically state that the silent was far more action-packed and overall a better picture.

Worse, it is Eric, a Swedish character, who kills Fitz and not Snowflake. (Probably as a balance for the villainous Knitting Swede character, Hollywood wouldn’t want to be prejudiced, would it?) Newman doesn’t flog Swope to death in a fit of cinematic righteous fury, he just puts him in irons. In general, the film sounds like taking a shower with a raincoat on compared to the silent but, you know, talking.

As a rule, the lost silent films that grab all the headlines are the totally lost pictures that are rediscovered in one go, an entire print shows up. Beyond the Rocks, The Unknown, the 1916 Sherlock Holmes. However, there are hundreds of silent films that exist in part but have to be reconstructed from elements held by different archives. Sometimes it’s just a single missing reel, sometimes it’s a jigzaw puzzle with hundreds of fragments. These stories aren’t nearly as sexy to the media (with anything less famous than Metropolis, anyway) but are every bit as important.

Like most silent era studios, Columbia wasn’t careful with its own history. They had remade The Blood Ship as a talkie, who needed the silent? When the studio was in the process of producing a documentary about its history for its 75th anniversary, the production team realized they didn’t have a single frame of The Blood Ship. The BFI had a partial print, six reels out of seven with the final one missing, and the documentary producers made do but The Blood Ship had joined the ranks the incomplete and not really screenable silents. However, a 16mm print with the final reel intact was later found at UCLA and The Blood Ship was finally complete for the first time in 80 years.

And then… nothing. The majority of all silent films are lost but so many were made that even the surviving fraction means there are thousands of them. However, only a few are available to the general public and the rest are sitting in vaults, never seen outside of academic circles except for occasional screenings. With no screenings near me and no home media release of The Blood Ship on the schedule, I had no way of watching it. The picture has been on my most wanted list for over a decade and I had to be satisfied with reading vintage reviews and studio marketing material. Until now.

So, after all this, does the picture live up to the hype built up in my head and heart over the past 15 years? I’d say it does. You can see where the production team referenced, borrowed and outright stole but they stole like artists, making sure all the borrowed elements fit together in their gory nautical yarn. It’s not a movie for everyone (though, obviously, Photoplay was incorrect to state that women would want to be excused) but if you’re already a fan of Bosworth’s sea salt vengeance or if you like your action on the dark side, this is the picture for you.

Where can I see it?

A beautiful restoration was released on Bluray by Sony with a score by Donald Sosin. Do check it out, it’s a quality release.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.