In this Latvian animated feature, a sudden flood and rising waters drive a cat from its home and into a sailboat filled with creatures from across the continents. A gentle meditation on life that lives up to its title.

Home Media Availability: Bluray release announced but no date currently available at the time of this review. Available to stream from most major USA services.

Sailing for parts unknown

(Note: Since the movie is animation and suitable for family viewing, I will mention that there are moments of suspense but none of the animal characters die, though there are some sequences that could be interpreted as symbolizing death. Ultimately, it is a hopeful picture.)

I won’t leave you in suspense: the hype is real and Flow is a lovely, engrossing picture, deserving of all the laurels it has received. With that out of the way, let’s take a dive into why it is such a successful film and how this success ties into old school visual filmmaking.

Flow’s plot is based on the emotions and growth of its all-animal cast and doesn’t have anything resembling a traditional structure. As its title implies, the viewer is brought along on a risky but ultimately kind-hearted watery ride accompanied by a black cat, a yellow Labrador, a capybara, a lemur, and a secretarybird as they attempt to navigate a sudden and almost supernatural flood.

This being the case, a blow-by-blow recap of the events of the film wouldn’t be helpful in reviewing it because so much depends on reading between the lines. Flow is a challenging film and not just in the Pixar “feelings have feelings” sense. The heavy and ambiguous symbolism and circular narrative invite rewatching and discussion and each viewer’s interpretation will inevitably depend on their own beliefs and experiences.

For example, in my mind, the animals are all archetypes with the cat having to overcome shyness and fear, the capybara being kind and sensible but not a natural leader, the Labrador means well but is susceptible to peer pressure and is too oafish for the more refined creatures, the lemur is obsessed with earthly possessions to the detriment of its own safety, and the secretarybird, as the film’s apex predator, is punished for a display of empathy. The whale that appears throughout the film is a mythical other and its final scene within the film shows that a miracle can often cause unexpected harm (though the post-credits scene offers hope).

The motley crew of mismatched beasts may have a rough start in their adventure but the creatures who stick to their own kind are not punished within the narrative but they also do not grow and do not experience the eventual joy of teamwork and cross-species understanding.

The flood (is it a symbol of stress, tragedy, life itself?) is a character in itself, driving the plot with its unnatural speed and sudden calm. The world is devoid of humans, though their echoes remain everywhere in the form of buildings, bottles, sculptures and knickknacks that the animal cast encounters on their voyage.

It reminds me of silent star Colleen Moore’s fairy castle, a miniature that cost half-a-million dollars in 1930s money. Moore wrote that when she tried to add dolls to the house, they looked static and dead. When the house was empty, it was easy to people it via imagination and conjure up images of its inhabitants running with the fairies.

It’s no wonder that a silent film star would hold such an opinion, silent movies require active work from the viewer’s imagination to truly shine, and the echoes of people in an empty world is the mood that Flow evokes. Was it a sudden tragedy that took the people away? The film is sometimes described as post-apocalyptic but there’s no apocalypse to be seen beyond the signs of past floods. The home that we see is in disrepair but no indication of tragedy within. Was it a gradual abandonment, as we now understand Skara Brae to have been, or what seems to have been an evacuation hiding a grisly truth, as was the case with Pompeii?

Whatever your thoughts on the film’s message, meaning and symbolism, and they are sure to be different from mine, it’s a picture stays with you and invites you to experience its mysteries and movies that do this are particularly welcome in a pop culture landscape that builds its economy on explaining everything to death. Prequels and prequels to prequels painfully explaining every detail, tying every loose end, smoothing over every inconsistency. Flow, with such a unique mood and willingness to trust its audience, is swimming against that current and it’s no wonder that the film swept major awards since its release. However, its biggest upset is what really put it on the map.

Since its launch, the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature has consistently either gone to big studio names with $100 million+ budgets (adjusted for inflation), particularly Disney/Pixar, or to established legends in the animation world (Ghibli, Aardman). Smaller independent films have been nominated in the past but have not been favorites to win even as indies have become a force in the live action categories. Indeed, predictions went overwhelmingly for The Wild Robot (Dreamworks).

It was a fairytale ending for Flow, a film that cost a sliver of a Pixar or DreamWorks release and was animated using free and open-source graphics software. Director, producer and animator Gints Zilbalodis and his Latvian delegation charmed social media with their cat-themed accessories and their joyous post-Oscars In-N-Out feast.

Flow wasn’t the only upset of the ceremony but its victory was such a pleasant surprise that interest in the film spiked, as did discussions of how, exactly, it should be categorized. And here is where we come to the heart of my interest in Flow: is it a modern silent movie? Well, Jacques Tati was an acknowledged influence on Flow but Zilbalodis himself stated that his film was not actually silent but rather dialogue-free.

Now, contradicting someone about the nature of their own movie isn’t exactly wise but I would like to add context to the discussion. After reviewing so many silent movies, it’s a bit strange for me to have to think about the basic nature of the art — what exactly makes a silent movie a silent movie? — but, in fact, a great many sources do define a silent film as a movie without a recorded soundtrack of any kind.

I don’t agree with this definition for numerous reasons. Most importantly, movies have been an audiovisual medium used in tandem with recorded (or at least reproduced) music from the very beginning. There is the Dickson Experimental Sound Film from 1894, of course, but on a commercial level, the Edison Kinetophone was a peepshow machine that played recorded music along with moving pictures via a contraption best described as “communal earbuds.” (Edison would later reuse the brand name for his doomed attempt to popularize talkies in 1913.)

In the lead-up to and during the talkie revolution of the late 1920s, synchronized soundtracks sans dialogue gained popularity and became a prestige release feature on par with color. Nobody is seriously arguing that Don Juan, Sunrise, The Man Who Laughs or Show People aren’t silent, for example, even though they have recorded synchronized scores, synchronized sound effects (some of which drive the plot) and even vocal music with lyrics in the case of the latter two films. When Charlie Chaplin released City Lights in 1931, it was widely accepted as a silent film despite its synchronized score, sound effects and indecipherable vocal sounds (but not dialogue).

Even before recorded scores were the norm, there were other methods of pre-loading music into a silent movie. For example, the 1922 experimental classical music film Danse Macabre offered special player piano rolls to sync with the onscreen action. And, while not technically recorded, there were official cue sheets provided for some films, as well as full scores. (Full scores being generally reserved for more prestigious productions.)

Multimedia presentations (motion pictures, glass slides and more) like the 1900 Australian Salvation Army production Soldiers of the Cross, as well as the 1908 L. Frank Baum extravaganza The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays, offered elaborate musical scores. On the pure motion picture front, Georges Méliès offered a bespoke score for The Kingdom of the Fairies (1903) and celebrity composers like Camille Saint-Saëns and Mikhail Ippolitov-Ivanov contributed their fame and skill to the movies in 1908, kicking off a new era in film music.

Such music was sometimes interactive. Ippolitov-Ivanov incorporated the folk song Mother Volga into his music, turning the film Stenka Razin into a singalong experience that Russian audiences heartily embraced. Slides and short films designed for singalongs were a staple of the magic lantern and motion picture eras; it’s no surprise that “follow the bouncing ball” song films were a silent film innovation.

The power, importance and ubiquity of music was acknowledged from the very top of the industry. MGM wunderkind Irving Thalberg plainly stated that “there never was a silent film.” He recalled how a totally silent screening of a new picture would be painful but then they would call in a musician to pound out a score and suddenly the movie worked. (MGM was the last major Hollywood studio to embrace sound movies.)

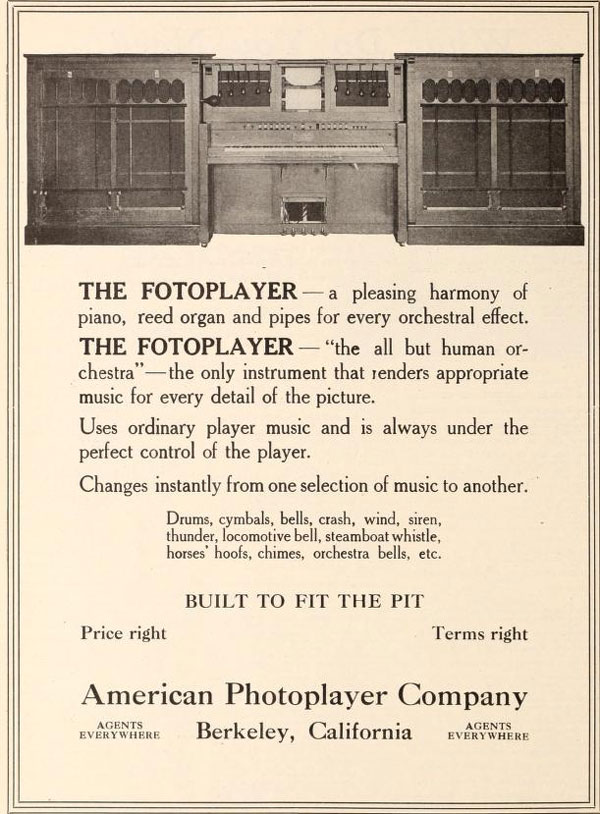

Synchronized sound effects were likewise available before recorded soundtracks became the norm. There were fancy machines like the Fotoplayer, a combination player piano and sound effects rig, but many theaters relied on the simple pairing of a pianist and a percussionist, the latter providing the effects in time to the action onscreen. (Well, that was the idea anyway. In practice, it depended on both the sobriety and attention span of the performers.)

The Excelsior Sound Effects Cabinet billed itself as an all-in-one solution for adding mood and realism to moving picture shows and promised that their contraption could provide the following sounds: “Locomotive effect, foundry effect, rain, wash of waves, motor boat, pulley and hoisting, donkey bray, sewing machine, torn torn, phone bell, engine bell, sleigh bells, spurs, anvil, church organ, horse trot, china and glass crash, hail, roar of waterfall, automobile exhaust, baby cry, police rattle, slap sticks, railroad whistle, bicycle bell, door bell, tin rooter [festive noise-maker], sword clash, church chimes, telegraph, steam exhaust, wind — light and heavy, thunder, dip of oars, automobile horn, duck quack, flying machine, drum, cow moo, cow bell, patrol and fire gongs, bird whistle, fencing, steamboat whistle, closing doors, lion, elephant, tiger and bear growl combined; cannon, rifle and pistol shots — single or in volley, etc.”

Got all that? And now I want to see the movie that needs ALL of them!

Another interesting thing about the perception of what makes a silent film is the intense fixation on title cards. First, we must understand that dialogue title cards were optional in the early years of movies and not present at all in the earliest projected cinema. You can see an early example in the Cecil Hepworth trick film How it Feels to be Run Over (1900), which concludes with “Oh mother will be pleased” flashing across the screen.

As the 1900s wore on, it was more common to see titles that described the scene about to be played rather than spelling out dialogue. Dialogue cards began to dominate in the 1910s but even as their popularity increased, there was a movement to cut back and even eliminate them where possible. Telling a story through purely visual means was seen as a high form of art. A successful example of this approach can be found in Warning Shadows, which tells a complex tale of adultery, jealousy and murder with only a few introductory titles, relying entirely on acting and cinematography for the rest of its runtime. Even films that fully embraced dialogue cards expected the audience to read expressions, gestures and lips rather than transcribing every line “spoken” onscreen.

Title cards are so deeply associated with silent filmmaking that The Artist (2011) and Silent Movie (1976), both technically part talkies as they contain synchronized and decipherable spoken dialogue, are easily accepted as silent movies because they make liberal use of titles and therefore fit into the modern perception of silent cinema. However, romance languages use a term that literally means “mute film” to refer to the silents, which I feel is far more accurate. In fact, the term “silent film” was actually coined before the talkie revolution as a way to differentiate it from the spoken stage. It has always been about the dialogue.

Silent movies re-released during the sound era would sometimes be presented as-is but, since title cards were so tied the old, out-of-fashion way of filmmaking, the distributors sometimes also took drastic measures. The part-talkie She Goes to War had all its title cards stripped out, leaving a surreal and disjointed narrative. Charlie Chaplin famously recut The Gold Rush, getting rid of the titles in favor of plummy spoken narration.

The attempts of silent era filmmakers to cut back on or eliminate title cards have been largely forgotten and many modern silent films make the mistake of assuming one line of dialogue = one title card, leading to tedious and choppy films. Title cards needed to punctuate, enlighten and somehow enhance the picture by either moving the plot along or delivering some snappy bit of wit, ideally both at the same time. The job was so important that it had its own Academy Award category and books on screenwriting warned that titles were a specialty field, not to be attempted by a mere scenarist.

All this is to say that silent films made liberal use of any sound except synchronized dialogue and their main goal and focus was to convey their story as visually as possible. Such an approach required the filmmakers to trust their audience. As brought out earlier, with no audible dialogue to lean on, the viewer would have to supply some of the imagination and meet the movie halfway.

A movie like Flow fits well into that ethos. There’s nobody to smoothly explain the culture of the secretarybird or why the lemur acts that way but we understand everything through carefully chosen visual information, punched up by appropriate sound effects and music. “Show, don’t tell” is so commonly repeated in writing courses that it has almost lost its punch but that is the essence of silent cinema and Flow. I don’t think the film could have been clearer if it had reams of Star Wars-esque introductory scroll and a narrator explaining everything. That’s not easy.

Silent films were economical as well. While there were certainly examples of bloat, as there are in any era of filmmaking, silent movies tended to be lean and nimble with nothing wasted. Flow is a remarkably economical film and I am not talking about money. It feels lush and deep but there isn’t a second of wasted screentime.

Finally, Flow is friendly to the international audience. While there was hanky-panky with quotas, multiple embargoes and dirty deeds with film rights, the silent era, particularly pre-WWI, was remarkably international with mainstream, average moviegoers enjoying films from around the world on the same program. The lack of dialogue and clear emotional narrative mean that a film produced by a Latvian team can be enjoyed anywhere in the world. (The almost-totally-silent Aardman series Shaun the Sheep enjoys international appeal as well, reaching 170 countries.)

However you categorize it, though, Flow is one of the most interesting and exciting animated films to come along recently and its embrace of visual storytelling and symbolism is most welcome. Some movies stick with you by smacking you in the head but Flow is more of a gentle dance, inviting the viewer to experience, interpret and enjoy and is all the more memorable for its subtlety. Well worth seeing.

Where can I see it?

Slated for 4K Bluray release from the Criterion Collection but no date has been announced as of this writing. Currently available to stream in the US from most major platforms.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

I had the chance to talk to Gints weeks before he received the Oscar. Two remarks: He also composed the soundtrack/music for FLOW…. and when I mentioned some “technics” of drawing which reminded me of Richard Williams, the animator and his last opus “Lysistrata”, Gints confirmed that he knows Williams’ film. Best Günter A. Buchwald

So much talent!

The scene with the cat trapped atop the statue as the waters rise was one of the most affecting of the year, not least because I now have a cat.

Yes, so many memorable scenes