An heiress on the verge of bankruptcy uses the last of her money to finance her inventor lover’s creation: the video call. They marry but years pass and the inventory decides that perhaps his wife is a bit boring and he deserves a new romance.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Wrong Number

Silent era entertainment would sometimes venture into “after happily ever after” for its plots. For example, Cecil B. DeMille’s Saturday Night picks up where other films might end: after the against-all-odds marriages between a socialite and her chauffeur and a wealthy man and the laundress. Up the Ladder is another example of this, starting up where most movies ended and showing what happened next.

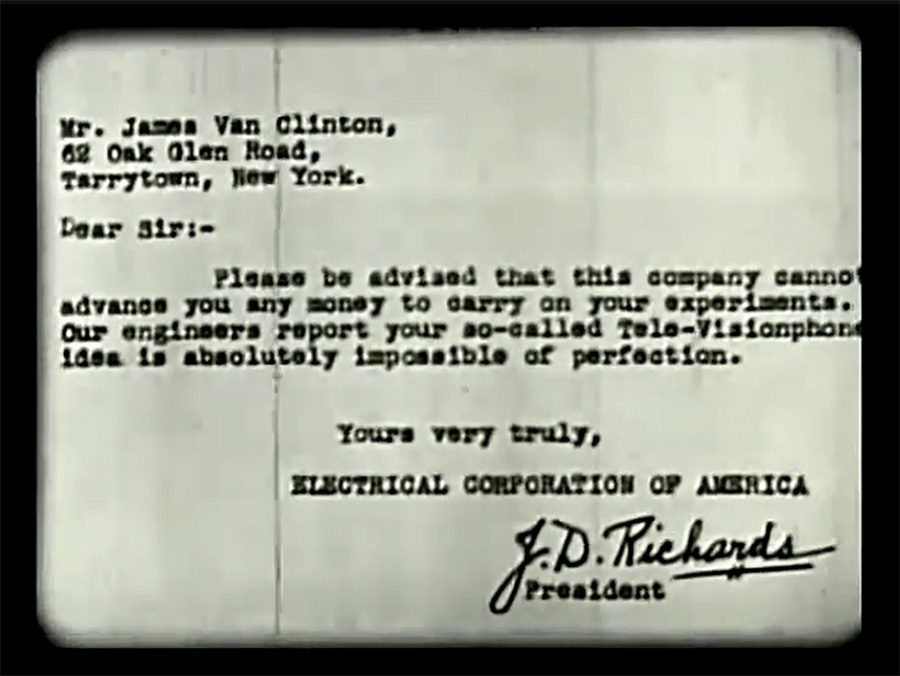

Jane Cornwall (Virginia Valli) is a jet setting heiress so stylish that she managed to pre-date jets. She returns from a world tour and immediately stops by to visit James Van Clinton (Forrest Stanley), whom she has loved for years. He is an inventor, completely immersed in his work but he has a problem: his invention is ready but he needs an infusion of cash to get it to market and his family fortune is long gone.

Van won’t take money from Jane, so she returns home to plan things out with her financial advisor, Judge Seymour (George Fawcett). Seymour informs her that all of her investments have gone bust and she will need to sell her mansion in order to stay afloat. Jane has him sell but orders him to give the money to Van, posing as an interested investor. Jane moves into a small cottage.

With the money, Van perfects his invention, a video call machine he calls Tele-Vision (has a certain ring to it, no?). Success is knocking and he takes the opportunity to propose to Jane via conference call. Five years pass, business is booming but Van has changed.

Success has gone to his head and he is now involved in an embarrassingly obvious flirtation with Helene Newhall (Margaret Livingston, who specialized in this kind of thing), an old friend of Jane’s. Helene’s husband, Bob (Holmes Herbert), suspects something is up, as does Jane, but neither say anything.

Jane and Van’s little girl, Peggy (Priscilla Moran), is a candy-munching machine and is always asking her father to bring boxes of sweets home to her. He is forgetful, so he allows her to fetch the candies from his coat pocket if he fails to give them to her when he comes home.

I think we can all see where this is going…

On the evening of Jane’s birthday, Van arrives home but declares that he has an important business appointment. (Well, it’s a kind of business.) Peggy efficiently searches his coat pockets while he is in the bathroom but the box doesn’t contain candy, it’s a piece of jewelry with a hand-written love note inside. Jane assumes that it is her birthday present and has Peggy return it to the coat pocket.

Well, Van leaves without giving Jane the box. Feeling lonely, she calls Helene to see if she and Bob can come over for a party. Helene claims a headache via video call but she unwisely placed her machine across from a mirror and Jane sees Van’s reflection.

To cheat on one’s wife is cruel. To cheat on one’s silent business partner is foolish. Cruel and foolish Van is in a whole heap of trouble.

A quick note on this film: the version on home media seems to be incomplete with chunks of footage missing especially from the last reel. I had to check reference materials to confirm that my interpretation of the finale was the one intended.

The production seemed to have been a troubled one generally. In an era of rapid turnaround, the project was first announced in late 1922 with shooting set to commence in weeks. Hobart Henley was attached as director, per the AFI, but a 1923 Universal ad for the 1923-1924 season announced the picture would be directed by Henry Pollard. Edward Sloman was the final choice for director. I don’t believe anything was shot in 1922 or early 1923 as little Priscilla Moran would have been just four at that time and she is clearly far older in the final film.

(Spoiler) I have seen my share of marital dramas from the silent era and there are a couple of annoying ways the film could have gone but didn’t and I am delighted. First, Jane has absolute proof that Van is cheating with Helene. Her character is quiet and serene, a thinker, and I feared that she would turn to noble and stoic sacrifice in order to give Peggy married parents. Hell no! Jane is out to teach her daughter self-respect by example. She confronts Helene with her adultery and tells her off before turning her rage on Van.

Van has refused to come home and, due to his neglect, his business is in danger of being foreclosed on. Jane can save the business if she sells her shares and takes on a new partner but she isn’t sure if she wants to do that. The business turned Van into a louse, is it worth saving? Van rushes to the office but it’s too late, Jane has let the business fall and the new owners are taking over.

Van and Jane separate, Jane taking custody of Peggy, and he is forced to take a subordinate position in research and development. The last scene of the film shows him receiving a promotion and pay raise– witnessed by Jane. The movie never specifies but is it possible that has pulled another double-cross and sold her shares after all, once again a secret silent partner and now her husband’s unambiguous boss? She already dealt behind Van’s back once, why not a second time? However, even if she did let the business fail and had nothing to do with Van’s promotion– wow, that’s an icy move on her part and I love it.

With this ending in mind, let’s discuss the writing of this picture. I wasn’t able to locate a copy of the original Owen Davis play upon which this film was based, so I am not entirely sure how much of the story was his and how much was added by screenwriters Tom McNamara and Grant Carpenter. Whoever was responsible, this is a very smoothly written film, with its light sci-fi elements enhancing and not distracting.

(Incidentally, this wasn’t the first video phone picture. The 1912 French film Amour et science features a woman tired of playing second banana to her inventor lover’s work and so fakes an affair via video conference call to make him jealous.)

What is so interesting about this plot is that it is an inversion of the typical working woman story that would be popular well into the mid-century. Sure, a husband can tolerate his wife’s career but she needs to acknowledge where her real duties lie and those are as a wife and a mother! And sure enough, she always sees the light before the credits roll.

Well, in Up the Ladder, Jane is willing to indulge Van’s fantasies of being a businessman and selling his little invention but when he hurts her, she brings the hammer down. No noble sacrifices to preserve her marriage to a cheater, none of the “leave them alone and they’ll come home wagging their tails behind them” nonsense we see in films like The Women (1939). Van has been out of line and Jane slaps his hand, giving Helene hell too for good measure. She built him, she destroys him.

But there was a happy ending, right? He’s promoted in the end, right? It’s implied they will reconcile, right? Yes, but the implication is that now he knows who his real boss is and that she can cut him off at the knees whenever she likes. I have never seen anything like this in films of the era. There have been comedies where the heroine emasculates and dominates her way to a happy ending but very rarely dramas. (Especially in dramas that were written entirely by men.)

Director Edward Sloman was so very good at this kind of picture. His People, released the same year, is also full of beautiful, subtle performances in scenarios that could have easily fallen into melodrama. I love the performances of Valli and Moran particularly, Valli’s steely determination when she realizes she must destroy her husband and Moran’s tears when she puts together that daddy didn’t give mommy her present (an unfulfilled promise of a present being one of the very worst things an otherwise happy kid can endure). Reviews of the time were full of praise for Sloman, Valli and Moran.

Sloman encouraged underplaying, which means his films age well. (Most of them. We don’t talk about Surrender. Ever.) Stanley tended to go for big gestures and he is a bit broader than his co-stars here but pretty subtle for him. Herbert was always an underplayer, to the point of being deemed dull, but I loved him in the scene when he finds his wife in the arms of another man. Livingston played Other Women morning, noon and night in the silent era and is typically shameless here.

Up the Ladder received favorable reviews and feedback from theater managers stated that the film brought in audiences despite a heat wave during its release (air conditioning not yet being a ubiquitous movie theater amenity) and the people seemed to like it. It has fallen into obscurity, pretty much only discussed because of its “Forrest Stanley invents Zoom” angle, which is actually why I chose to review it myself.

This is a surprising film and its subversiveness is so subtle that it seems to have flown over the heads of audiences for a century. Up the Ladder is a bit of a sleeper and well worth seeing. Here’s hoping a less choppy print becomes available eventually.

Where can I see it?

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Van’s like “I never thought *my* actions would have consequences!”

“It’s unfair, if you think about it!”