Edison’s remake of the company’s own 1902 hit, incorporating all the latest special effects and a lead from the newly-minted star system. You know the drill, a cow for magic beans…

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of EYE.

Social Climbing

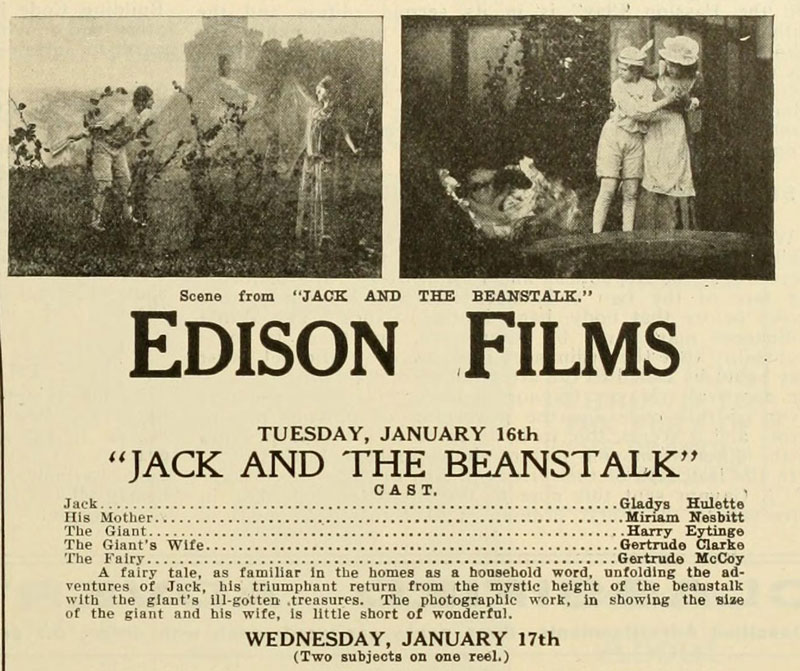

The Edison film company had been attempting to cement a monopoly on the movies since the beginning but it soon found that it had serious competition, both domestically and abroad. Fairy tale films were wildly popular, borrowing heavily from stage fairy extravaganzas and incorporating hand-applied color and only-in-the-movies special effects. The 1902 Edwin S. Porter film Jack and the Beanstalk was designed to rival these productions with its scenes of magic, its pantomime cow and its then-ambitious ten-minute runtime.

Jack had been good to Edison, and to the movies generally, and so the company returned to the well a decade later. Audiences didn’t just want razzle-dazzle anymore, they wanted stars and the star system had arrived in the United States in 1910 with IMP (proto-Universal) advertising Florence Lawrence by name, breaking an industry anonymity policy for actors. (This on the heels of French star Max Linder being billed by name in posters in 1909.)

Gladys Hulette was among the first wave of stars, a child actor who had made her mark as brats, rascals and gamines over at Vitagraph. Now sixteen, she was starting to age into more mature parts but she had experience in both trouser roles and special effects-laden fantasies, playing the tiny pyromaniac heroine in Princess Nicotine (1908) and Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1909). She was a natural choice to play Jack.

J. Searle Dawley had directed the famous Edison Frankenstein (1910), as well as the company’s 1909 version of Hansel and Gretel, so he was also no stranger to fantastical imagery. Dawley would go on to direct the 1916 version of Snow White, which was a major inspiration for the Walt Disney animated film. While I am cautious about attributing firsts, Dawley’s name should be mentioned among the early pioneers of fantasy imagery as we know it in the movies.

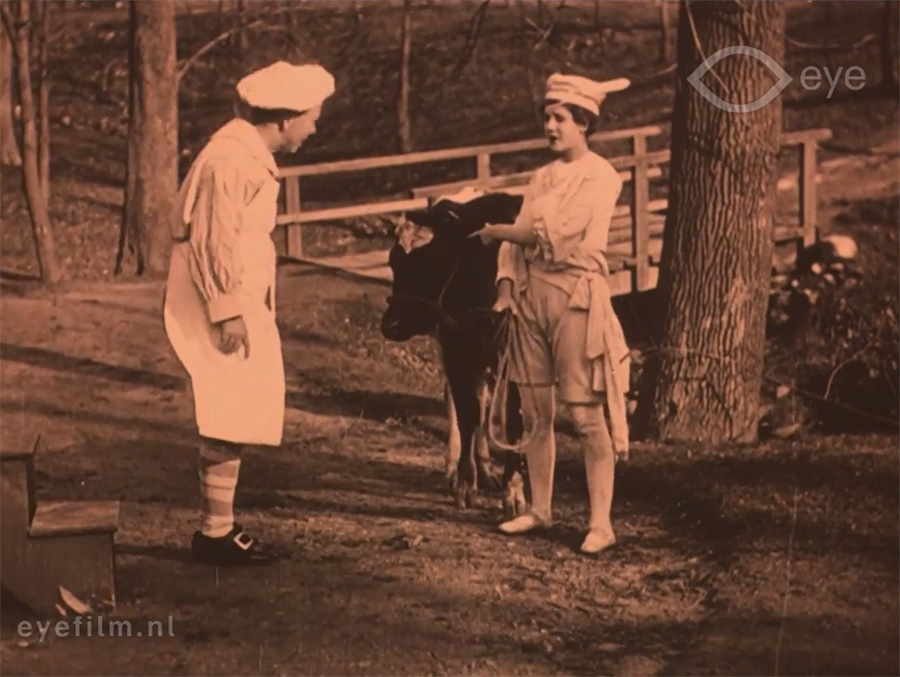

(Quick note: the version I viewed for this review is a Dutch release print and it seems to have some changes from the American release. I will examine these possible changes later in this review.)

The film opens with a giant invading a castle and kicking out its lord and lady. It is indicated but not shown that the giant murders the lord. Later, we see Jack and his mother, the former lady of the castle (Miriam Nesbitt), are living in poverty. In desperation, Jack takes their cow to town to sell it. Of course, we all know that Jack will fail at his mission, instead swapping the cow for a hatful of magic beans. Angered by his silliness, his mother throws the beans out the window, where they immediately grow into a rather ladder-like beanstalk.

Jack declares he will climb it and up he goes into the sky. Once he arrives at the top of the stalk, he is greeted by a fairy (Gertrude McCoy), who offers to help. Jack reaches the door of the castle, where he meets the giant’s wife (Gertrude Clarke), who offers the boy a meal. The giant (Harry Eytinge) returns and Jack vaults into a cooking pot to hide.

This iteration of the giant is a nasty piece of work indeed. In addition to the usual “I’ll grind his bones to make my bread” cannibalism business, the giant berates and abuses his wife, who cowers in terror and tries to make sure Jack in safe.

Jack quickly sets about robbing the giant, taking his gold and his harp before being pursued down the beanstalk. The fairy trips the giant and the film ends abruptly just as the giant hits the ground, possibly a case of nitrate decay.

Hulette proves once again that she was a star in her charismatic turn as Jack. She interacts with her costars naturally, even when she could not possibly have been in the same room, and brings a puckish charm to the role as she gleefully robs the giant of everything. Eytinge and Clarke are hidden under pounds of makeup but are suitably lumbering to convey their character’s massive size.

The 1902 Jack and the Beanstalk had been ambitious but it had not attempted to create the giant’s size out of whole cloth. Instead, Porter had employed the standard “absolutely massive human as the giant, petite player as Jack” technique. The 1912 version dreams bigger, a lot bigger, and visualizes a giant with shins the height of a grown man. And that meant work! A whole lot of work.

The special effects are remarkably smooth and clever. It appears that the giant and his wife were filmed on full-size sets, while Hulette and the props she was to steal were shot on a carefully-matched black background in double exposure. Hulette was dressed in white or pale blue and the props were similarly light, which meant they stood out against the dark background of the giant’s castle set and appeared solid rather than transparent, as is usually the case with double exposure. There are a few cases where the illusion breaks: you can see that darker shadows, the folds of Hulettes trousers or the stripes of the bag, for example, become see-through but generally, the illusion is excellent.

Dawley’s team was particularly clever about the props. The giant’s basket, for example, was made twice: a normal-size prop for the giant and a larger version for Jack to steal. The giant lowers the basket to the floor and Dawley uses a substitution splice, removing the basket from the giant shot and adding it to the Jack shot. Again, carefully matched on two different sets with some minor jumps and jitters but impressive overall. As the trade magazine Moving Picture World puts it, “It is a trick picture of course; but there is very little in the scenes to suggest that the relative sizes of Jack and the Giant are not as they seem to be.”

The care and skill of Dawley and his team is remarkable. Even though I am fairy certain that I know how everything was done, I cannot imagine the precision required to make sure that it all went together so seamlessly.

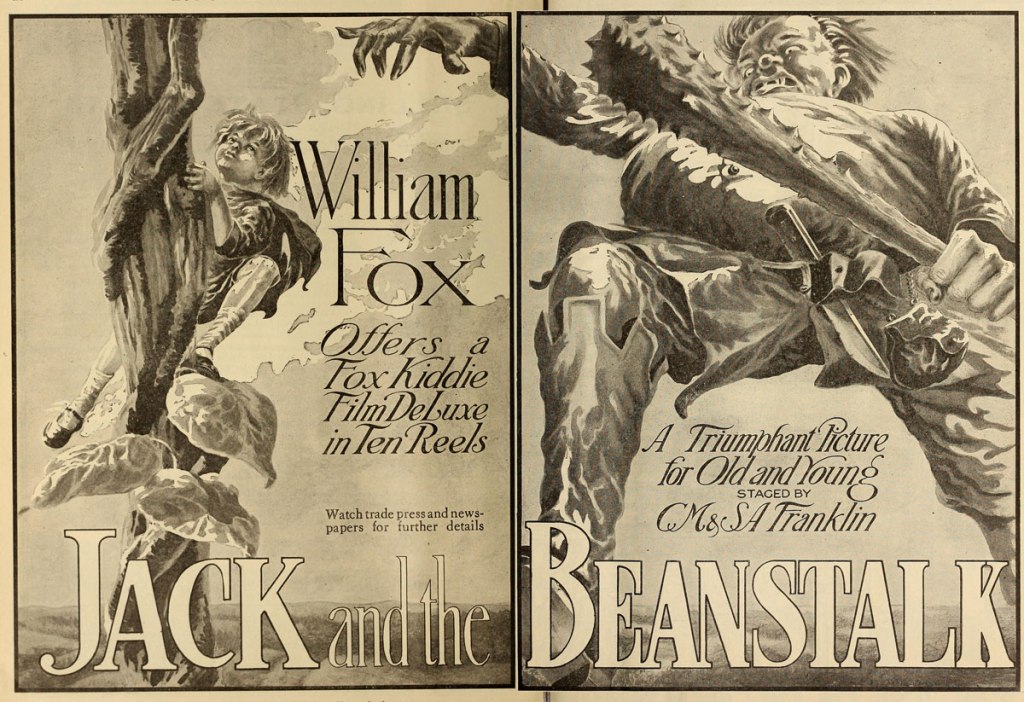

Jack’s tale was one of the favorites to film during the silent era. In addition to the Porter version, there was an all-child cast version from Thanhouser in 1913, mentions of a Kinemacolor film released around the same time, a 1917 “Fox Kiddies” all-child cast version, a Walt Disney animated version in 1922, a Baby Peggy picture in 1924, and a silhouette animation the same year. In the sound era, animators from Max Fleischer (with Betty Boop, of course) to Lotte Reiniger to Ub Iwerks to Chuck Jones and Friz Freleng both sending Bugs Bunny up the beanstalk (Jones sent Daffy Duck too for good measure.). In short, Jack was hot stuff, on par with Cinderella and Snow White in popularity.

Jack’s star has faded somewhat in recent years, despite one big budget attempt to turn the tale into a blockbuster. The story in its unaltered state feels a bit colonial (or at least home invasion-coded) for modern tastes but are they really so modern? The prologue in the 1912 film shows that giving the giant a more villainous nature was a priority for filmmakers far earlier than we may have assumed. In fact, the filmmakers were on solid literary ground, with a push and pull between Jack the Marauder and Jack the Liberator for the past 300 years.

The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean was published in Round About Our Coal Fire, Or, Christmas Entertainments in 1734 and contains many of the elements we associate with the story, including an early Fee Faw Fum– and quite a few we don’t! For example, towns sprouting up on the beanstalk leaves with public houses included. It’s breathless, frenzied, unspeakably weird, told by a satirical, unreliable narrator and would probably make an amazing movie.

The 1807 version, The History of Jack and the Beanstalk by Benjamin Tabart, is generally reckoned to be the earliest proper Jack story published and it makes clear that the giant is a thief and the murderer of Jack’s father. Jack does not know this prior to climbing the beanstalk but he is informed by a fairy at the top and is therefore justified in his raid on the giant’s property.

Australian folklorist Joseph Jacobs published his own version in the 1890 collection English Fairy Tales, which removed references to the giant being the thief and the murderer and makes Jack a conquering bandit. Whether or not this is the most authentic or original version is up for debate but a conqueror attacking a “cannibal” and stealing his stuff would certainly have fit in with pro-colonial anglosphere sentiments of the time.

Both Edison films subscribe to the Tabart version of events but they handle this information differently. Porter has Jack guided at every step by a fairy, she even provides the beans that are sold to Jack, and she shows him the history of his family and the murder of his father through mystical visions. (All of this is clearly stated in the detailed synopsis published in the Edison catalog.)

Meanwhile, the Dawley version opens with a flashback of the giant entering the castle and driving out Jack’s parents. From the footage, it seems possible that either the death of Jack’s father was cut, or, since the film was aimed at children, it was never there to begin with and he was murdered via title card. However, I do wonder if this scene was meant to be a flashback near the middle of the film. All the synopses I have read make no mention of the prologue and there is other evidence that the film was originally in a different order. I would be curious to see what the version held by the George Eastman House is like.

The preference for Tabart would fit with the mood of the time as calls for film censorship and, if not censorship, at least more moral productions to stave off censorship, had become a common refrain. The Motion Picture Story magazine published a 1913 editorial by William Lord Wright, who extolled fairy tales, naming Jack and the Beanstalk among them, as superior to the gangster films that had been growing in popularity. He wrote:

“Permit the fairy tale to supplant the adventures of the “fascinating criminal” on the picture screen. Perhaps some good fairy has already become active, for, luckily, film stories of the “Raffles” type are disappearing from the releases. I think the fact a noteworthy instance of the advancement and uplift of the art. The pictures having to do with the adventures of “high-class criminals” are becoming a thing of the past. There are too many “crook” plays, so-called, on the real stage, and they have no part on the Moving Picture programs. Unlike the fairy story, the Biblical story, or the clean and uplifting and convincing comedy or drama, the “Raffles” playlets are surely not beneficial to children, or grown-ups for that matter. Such plots are becoming rarer because producers have found that, with a little research, there is an abundance of good and wholesome material to film, without resorting to doubtful plots having to do with denizens of the underworld.

I am pleased to assert that the editorials in The Motion Picture Story Magazine have been no small factors in the rapid strides taken by the Art of Cinematography within the past year.”

Note that The Motion Picture Story was a fan magazine and not a trade magazine. Trade publications were very much opposed to censorship and/or the infantalization of movie content and had their own peppery responses to such movements. (Wright’s own magazine even published these opinions on occasion.) And, as we all know, Wright was very much wrong about smooth criminals losing their appeal to audiences and studios.

However, he was right about one thing: critics and family audiences were very pleased with Jack. It received favorable reviews upon its release in January of 1912 and, by December of the same year, was used as part of Christmas programs to attract children and their parents to the theater. While actual box office takings from the era are opaque to say the least, it was given special screenings with some venues presenting it with orchestra music.

Speaking of music, The Moving Picture World regularly recommended musical pieces for accompanists and had several suggestions for Jack and the Beanstalk. I have linked to recordings of the pieces for your enjoyment:

Every pianist ought to be interested in playing for Edison’s “Jack and the Beanstalk.” The strides of the giant and the giantess may be caricatured by playing down in the bass something like the Raikaczy March; the distinction between Jack and the Giant may be suggested by playing the same thing higher up on the keyboard and faster. Mendelsohn’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream” (Smith’s transcription) is excellent while the Giant sleeps. For the most part the music should be graceful and animated somewhat like Chaminade’s “The Flatterer.”

By the way, this mention of graceful and animated music at the beginning of the picture, hardly suitable for a castle being raided and the hero’s father killed, further indicates that the prologue may have been a flashback or vision in the original English language release.

However the scenes were originally presented, Jack and the Beanstalk is an impressive and slick production that showcases how far cinema had come in just ten years. Porter’s Jack had been impressive in its narrative ambitions but Dawley’s Jack is a special effects showcase of great charm and personality. They would be an ideal double feature and even a full program alongside the readily available sound era Jack and the Beanstalk films.

This one is an effects nerd’s delight and fans of folklore will find a lot to love as well. Worth your time.

Where can I see it?

Stream for free courtesy of EYE with Dutch intertitles. There is no score but you could easily play some of the recommended pieces in the background for a 100% authentic experience.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Do You ever review any Films Directed by D.W. Griffith?

Yes, quite a few

Nice to see that the Edison film retains the point from the oldest versions of the story that the giant murdered Jack’s father. Without that, he’s just a burglar and murderer. That point is almost completely forgotten today.

Yes, I find it interesting that adding the backstory is considered moralizing but taking it out again is seen as authentic.

Wow. The film industry didn’t publicize its actors in its early years? Never read about that. Sounds like the way they treated voice actors in cartoons, years later.

Yes, they didn’t want to spend extra money on star salaries, so for much the same reason.