Or, the Dachshund and the Sausage, as its more descriptive alternate title puts it. An illustrator tries to put some life into his drawing, a little too much as the dachshund comes to life and engages in looting.

Home Media Availability: Released on Bluray.

Sausage Heist

Animation pre-dated the movies and was introduced to projected cinema early with classics like The Enchanted Drawing (1900) and the charming stop-motion in films like The Teddy Bears (1907) and The Haunted Hotel (1907). Winsor McCay, whose comic strips had already been adapted to the screen as live-action pictures, showcased his Little Nemo series as hand-drawn animation in 1911.

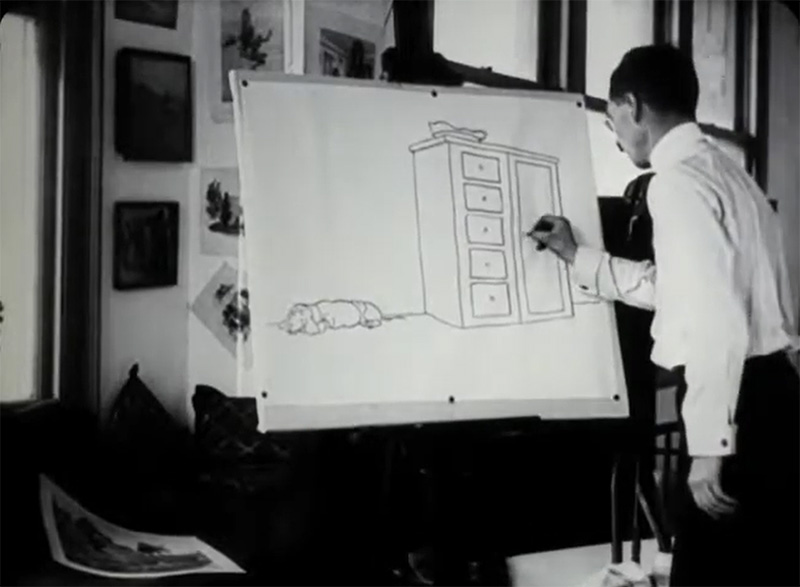

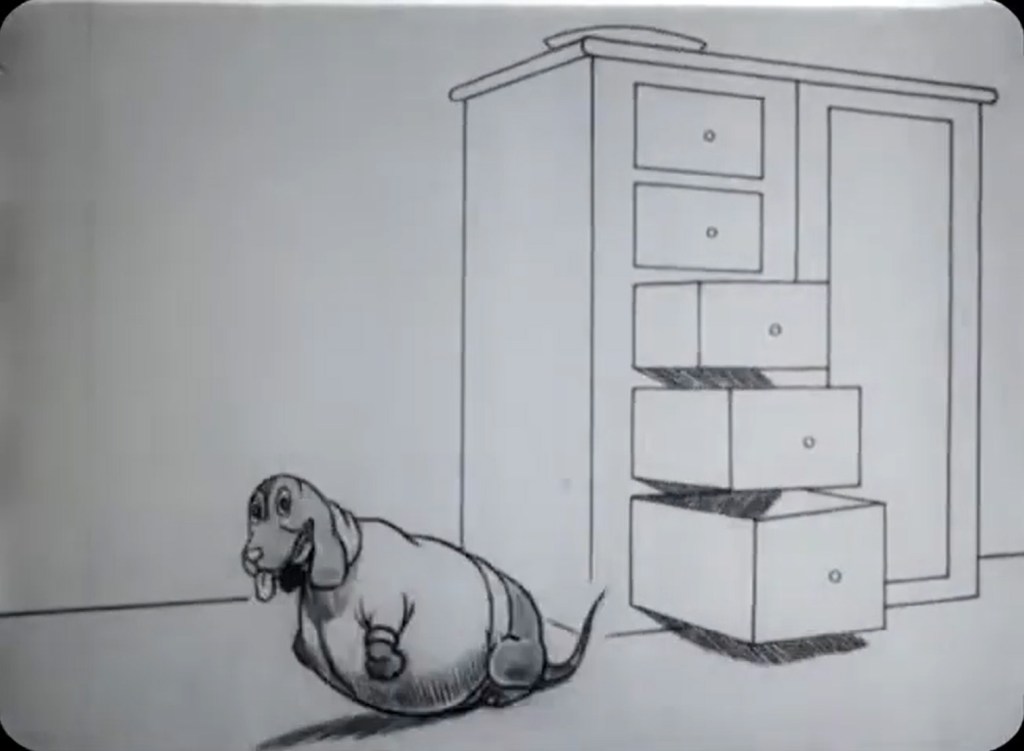

J.R. Bray, who helped put the “studio” in animation studio, entered the world of movies with The Artist’s Dream, which, like many cartoons of the era, featured a live-action frame story to introduce living drawings to the audience. Bray plays a cartoonist who has been commissioned to illustrate a dachshund longing for an out-of-reach sausage on the cabinet above. He is told that his illustration has no life and decides to take a break.

The dachshund doesn’t appreciate being described as lifeless and decides to take some action. He pulls out the drawers of the cabinet to form a staircase, climbs up to get the sausage and, after eating every crumb, closes the drawers again to hide his crime. The artist returns– he could have sworn he drew a sausage– and redraws multiple links for good measure.

Once he leaves, the Dachshund repeats his heist with the additional sausages. The feast inflates the dachshund’s belly so much that his feet can’t reach the floor and he happily rocks back and forth until he explodes. The artist returns to see the destruction and begins to think he’s gone mad… only to be awakened by his wife (played by Bray’s own wife, Margaret). What a dream!

(I should note that the version I saw only deals with the theft of the sausages, while trade magazines of the period describe the dog interacting with a mouse and a flea. I am not sure if there was an alternate version or if the film I saw was cut for re-release. Certainly, the title cards are not period accurate, using a typeface that would not be introduced until 1929/1930.)

This film is sometimes listed as the first to use cel animation and several history books repeat this. Cel animation was a labor-saving innovation credited to Bray and Early Hurd (we are NOT going to address the invention debate on this one, nor dig into the legal tangles of early animation). Rather than redrawing the entire scene for each frame, the background was drawn or painted in isolation and the moving characters were illustrated on a clear overlay, saving considerable time and reducing the labor needed to produce a cartoon.

Naturally, when this process was in use, the background would not have jitter. The Artist’s Dream, while beautifully drawn, has a jittery background that cannot be put down to a bad tripod or anything like that. Background lines move, in short. Plus, it was released before the cel animation patents were applied for, which doesn’t necessarily prove anything in itself but taken along with the shifting backgrounds, I think it says something.

I should also mention that this cartoon in particular is compared to McCay’s work, stating that Bray made superior use of shading while McCay merely did linework. I don’t think this is fair in the context of how the films were made: McCay’s film was designed to be hand-colored and Bray’s was not. It made sense for McCay to leave clean lines for the colorists.

What’s more interesting is to examine how Bray’s cartoon fits into the pop culture landscape of 1913. First of all, the film’s title is a play on a popular phrase that had been adapted into a popular stage magic act by David Devant, who was noted for not just conjuring but for charming his audience with his personality and storytelling. The Artist’s Dream was one of his signature acts and involved an artist mourning for his late wife, only to have one of his paintings of her come to life. Living paintings were a staple of another magician’s films, Georges Melies Méliès, who brought entire walls of posters to life.

The movies worked with even more variations on this theme: ancestors came to life and stepped down from their portraits, living paintings are used as a means of demonic torment, authors fall asleep and dream themselves into worlds of their own creation. So, Bray was working within an established framework but with a twist: rather than a beautiful woman, the artist’s dream is of a naughty dachshund.

Dachshunds, their breeders have always assured us, were bred for maximum badger-killing skills and not to be cute companions. However, nobody could tell the kaiser anything and his dachshunds were both the apple of his eye and, court gossip tells us, the terror of all German-speaking aristocrats. (Their blood-spilling antics, including killing Franz Ferdinand’s favorite pheasant, destroying priceless art and decor, and piddling on court dresses while the wearers curtsied, were breathlessly documented in a book entitled The Private Lives of William II & His Consort and Secret history of the Court of Berlin, from the Papers and Diaries Extending Over a Period, Beginning June, 1888, to the Spring of 1898, of a Lady-in-waiting on Her Majesty the Empress-Queen. So, grain of salt.)

Dachshunds had also won great popularity in the United States, where their distinct shape had made them popular subjects for illustration and advertisements. Their sausage-shaped bodies and their penchant for looting was already a well-established comedy staple by the early 1900s, so Bray was once again tapping into something popular with a twist– maybe he was even dealing with firsthand experience. (My great-grandmother had one and her ownership style was, I’m afraid, all too similar to the kaiser’s. Baron was a terror.)

Bray’s playful story and skillful style was met with immediate success. The trade magazine Moving Picture World raved about it, “The comedy in the dog’s actions is rich in laughter. The picture has the quality of the best series cartoons; but, given in almost perfect animation, it is infinitely better. A desirable offering.” The Moving Picture News similarly advised theaters to screen the film, “Some two thousand separate drawings were necessary to achieve this unusual illusion, and as it is a distinct novelty and will be a distinct hit, you really ought to book it.”

And I suppose that’s the sausage of the matter: firsts aren’t as important here as the appealing character of the film and the skill with which it was brought to life. It’s easy to see why this was a popular film and how Bray was able to build an animation empire.

Where can I see it?

Released on Bluray in the Cartoon Roots collection.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.