Actuality footage shot in the aftermath of the Great Galveston Hurricane of 1900, which remains the deadliest natural disaster in United States history.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Disaster Tourism

We tend to think of the pre-cable news days as slow to respond to breaking stories but the film industry, still just five years into its era of projected entertainment, was always hungry for new material and no event, glorious or disastrous, was allowed to pass by unfilmed.

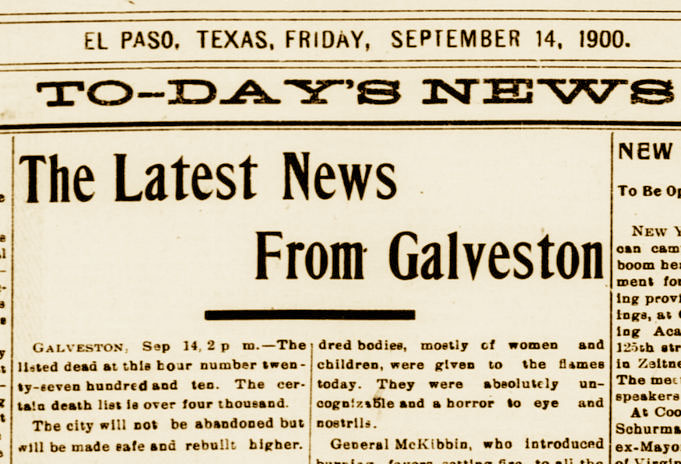

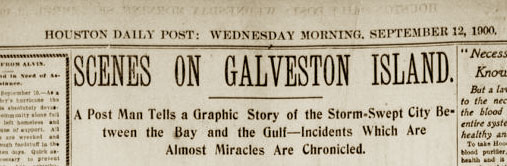

Having cut their teeth on events like the sinking of the Maine and the Spanish American War, American film crews were ready to disperse to the scene of the action. There are no known films of the Great Galveston Hurricane making landfall on September 8, 1900 but the Vitagraph crew was on site sometime between September 11 and 19 to capture the subsequent cleanup and recovery of thousands of bodies. The picture was advertised by title on September 22 and submitted for copyright registration on September 24.

(At this point, Vitagraph had a distribution deal with the Edison company, which can lead to some confusion in crediting the correct studio as Edison handled the copyright paperwork, while Vitagraph founder Albert E. Smith was the credited filmmaker.)

No bodies are shown in this footage– that would have been beyond the pale even in the wild west days of early cinema– but we see the devastation of the once-thriving port city as workers attempt to recover rotting corpses from beneath the rubble. The precise death toll is not known but it was at least 8,000 people on Galveston island alone, plus the destruction of over 2,000 houses.

The Edison catalog describes the scene on the ground: “Hundreds of dead bodies are concealed in these immense masses, and at the time the picture was taken the odor given out could be detected for miles.” As the bodies rotted, surviving residents were forced to burn en masse them rather than wait for identification and a traditional burial or cremation. In the film, the workers appear numb as they throw aside boards and chop at larger pieces of debris with axes. The Edison catalog states that a body was found while they were shooting and it seems like the workers in the right of the frame are uncovering something but, again, understandable numbness prevails.

It’s an eerie tragic scene, all the more powerful for its single-shot simplicity. While the Spanish American War films were meant to evoke feelings of patriotism and, frankly, jingoism, Searching Ruins is a true actuality, not commenting and merely capturing. (In fact, tensions due to the Spanish American War acerbated the problem as communications between the United States and Cuba’s weather stations were limited and Galveston was aware of the hurricane as it approached but its true danger was not ascertained or appreciated before it was too late.)

There was an outpouring of sympathy for the plight of Galveston but the entertainment value of the hurricane was quickly exploited as well, and not just in the motion pictures. A magic lantern slide catalog of 1902 make a slide series a featured item: “A series of 30 slides from photos taken the day after the storm, showing the streets of Galveston flooded, 10 story buildings totally wrecked. Ocean Steamers washed a quarter of a mile inland and other graphic pictures of the Texas Horrible Storm. The force of this unprecedented Gale and Tidal Wave is shown in these slides in all its horrors as only the camera can do.”

Slides had titles such as Tornado’s Bombardment of Ft. Arthur, Not a Wall Left Standing, Nothing Left in the Home but Brick, Seven People Buried Alive at this Corner (Houston), Home where all but Daughter were Killed, Removing the Dead in Wagons, Public School. Death Rate will Never be Known, The Burning of Fifty Bodies, Shooting of Robbers of the Dead and Galveston Cut off from the World by Storm.

The St. Louis World’s Fair of 1903 breathlessly boasted that “Another immense spectacle is to be the ‘Galveston Flood.’ The great building which is to house this entertainment is already completed. Here will be a wonderful scenograph, reproducing the terrible flood and hurricane which nearly destroyed Galveston on the 8th of September, 1900. Real water, thunder, lightning, the bay, the harbor, the serene city before the storm, the fearful storm in progress, the overwhelmed city– all these are to be shown in such wise, by means of a “flattened perspective” which the artist of the scenograph has patented, that the lifelikeness will be most vivid. Then the scene will shift to the rerisen Galveston, the beautiful city spring from its ruins, protected by its splendid sea wall, which is now building.”

Searching Ruins doesn’t offer any happy ending and, in fact, Galveston’s place as a premiere port on the Gulf of Mexico did not recover post-hurricane. But rebuild it did, even if it never recaptured its golden age.

(By the way, at the time of the Galveston disaster, the term “hurricane” was sometimes repurposed to mean a hit or powerful performance in the same way we use “blockbuster” today. For example, an 1895 stage production was billed as a “hurricane attraction” and an actress’s performance was praised as having “every sign of the ultimate hurricane” in 1899.)

Searching Ruins was not the first bout of cinematic disaster tourism and it would not be the last. Disasters from the San Francisco Earthquake to the sinking of the Titanic would find their way to movie screens in the immediate aftermath. The Johnstown Flood of 1889, which the Edison catalog cites in its description of Searching Ruins, would get its own epic big screen adaptation in 1926.

Questions about the line between the news and voyeurism are beyond the scope of this review but watching this film, even though it is not graphic, has the eerie feeling of walking on tombstones.

Where can I see it?

Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress. This is part of their paper print collection, which is derived from copies deposited for copyright purposes that were printed on photo paper. Some image details have been lost but they are sometimes the only surviving copies of rare early motion pictures.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

My grandfather was a Vitagraph cameraman, but long after the Galveston disaster (he worked for the West Coast Vitagraph studios). It’s always interesting to see what the old Vitagraph crew was up to. Thanks!

Nice!