A lonely shipwreck doesn’t remain lonely for long as a skeleton rises from the deep for a triumphant dance across the top of its deck. A double-printed trick film from forgotten pioneer Fred Armitage.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD in the Unseen Cinema set.

Rub-a-dub-dub

A quick note: Some sources list this film with a 1903 date. This is due to the fact that it was created in December of 1900 but only copyrighted in 1903. Movie copyrights were an odd beast at the time and, to make things even more fun, the film was offered in its studio’s 1902 catalog, adding a third date to the mix. I prefer to use the date of production, especially since we are focusing on the film’s innovative use of collage.

Projected cinema took the world by storm and with each passing year, audience hunger for new films increased. Movie companies tried their best to keep up with demand, sending camera crews around the world for actualities; engaging the services of stage, vaudeville, wild west show and burlesque performers for the camera; and improvising their own entertainments using only-in-the-movies tricks shots.

While repurposed footage and collage are generally associated with later eras of filmmaking, the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company had a slate of releases that pioneered the retroactive genre mashup. It was the work of Fred Armitage, who would later break ground by releasing The Ghost Train (1901, 1902 or 1903, isn’t early film dating fun), which collaged a negative image of a train with a cloudy sky to create a supernatural effect.

Armitage’s idea was deceptively simple: double print two films and thus create a new entertainment. Water was an ideal ingredient as there was no need to worry about a distracting jittery floor and a trio of these films were released consecutively in the Biograph catalog: A Nymph of the Waves, Davy Jones’ Locker and Neptune’s Daughters.

All three films used dancers along with nautical themes: A Nymph of the Waves combined footage of dancer Cathrina Bartho with shots of Niagra Falls rapids, Neptune’s Daughters combined an 1899 dance film called Ballet of the Ghosts with shots of a shipwreck. Davy Jones went one further by removing humans from the equation and combining a shot of a shipwrecked schooner with a skeleton marionette.

(The skeleton footage is sometimes identified as the 1897 Lumière film The Dancing Skeleton. This skeleton’s movements don’t quite match, though it’s possible there was another version released. In any case, skeleton marionettes were as popular then as they are today, so it would have been easy enough to obtain footage. Dancing skeletons were popular characters in animation that pre-dated motion pictures; different poses for the same figure were rapidly swapped to give an illusion of movement.)

The combination of the shipwreck, the puppet and the title creates a brief, humorously grisly atmosphere as the skeleton dances, loses its head and limbs and reunites with them atop the half-sunk vessel. Davy Jones was the personification of the bottom of the sea, specifically doom at the bottom of the sea, and, in this film, he is triumphant.

This may seem to be rather simple, it is just a puppet printed with a shipwreck after all, but it was innovative in its repurposing of exisiting films and the fact that its creator clearly took care to assure that it was thematically coherent and created a particular mood.

At the time of its release, movies could be viewed in numerous ways: through the peepshow machines the Biograph company named itself for, as part of dedicated motion picture programs that combined multiple titles (and magic lantern slides too), and as an added entertainment in a stage production.

Biograph’s catalog claimed that its films were compatible with all projecting machines using standard sprocket film, as well as Mutoscopes and various other peepshow contraptions. Cross-compatability was the name of the game. (At the time, motion pictures were tied up in patent wars and competing standards. Tale as old as time.)

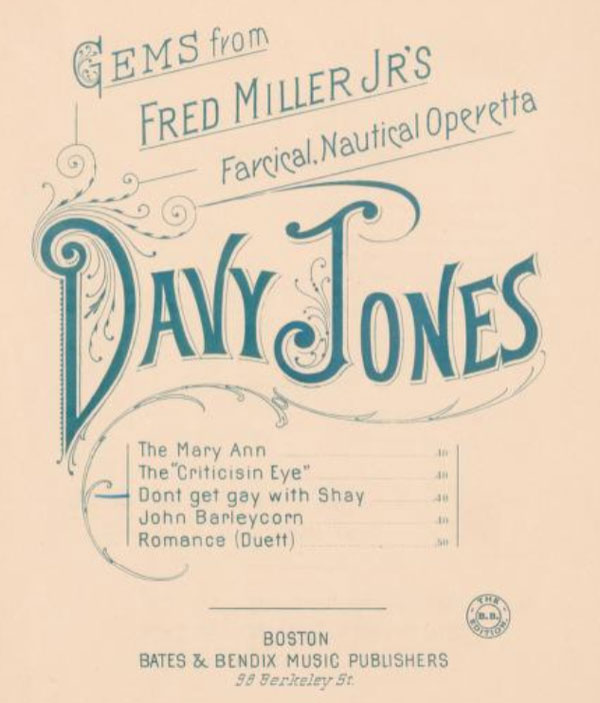

Davy Jones was having something of a pop culture moment at the time and was featured as a character, seen or unseen, in everything from children’s books to sheet music to operettas. How the Welsh got involved in an ocean graveyard and spirit of the oceam, I cannot say, the origin of the phrase “Davy Jones” has long since been lost to history and there are competing theories about how it came about.

(Fred Miller, Jr.’s 1894 “farcical nautical operetta” Davy Jones’ Locker had a long and successful run and, per its sheet music, featured songs like John Barleycorn and Don’t Get Gay with Shay. Unfortunately, it seems to have sunk into obscurity as deep as, well, you know.)

With this context in mind, it’s easy to see why Davy Jones’ Locker was made. And there was no false advertising or selling old prints as new, Biograph’s catalog is open about its methods: “Another double-printing picture made by combining a negative of a dancing skeleton with one of the wreck of a schooner. In the resulting picture, the skeleton appears to come from the hold of the boat, and to dance up and down the deck, his various members being disjointed and behaving in the most mysterious manner. During this weird dance the surf is rushing in from the ocean and pouring over the dismantled deck. A very effective scene.”

And indeed it is. As I discussed in my review of The Haunted Castle (1896), horror films of this period tended to incorporate humor with the chills. In introducing their trick films, Biograph stated that they liked to always include humor with their special effects as “the audience is more interested in mirthful magic than mere mystery.”

Still, the image of a cute incarnation of death dancing across the wreck of a ship and, presumably, the bodies of its crew is always going to have the power to disturb while it entertains and Davy Jones’ Locker succeeds.

They may seem simple in hindsight but Armitage’s experiments are still entertaining us today. If you enjoy recut trailers that turn family films into a horror, that’s the legacy of Fred Armitage. Davy Jones’ Locker may not be long on plot and was never meant to be but it has enough mood and creativity for days. I imagine that it was a happy addition to the mutoscope machine or motion picture show.

Where can I see it?

Released as part of the Unseen Cinema collection.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.