A horror anthology with five tales of terror taken from German and English languages sources, featuring Conrad Veidt, Reinhold Schünzel and Anita Berber as the leads in chapters, plus a frame story.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Chills, Five Ways

There’s nothing quite like a good anthology film. Combining several shorter stories into one longer film, often with a frame story to keep things tidy, quickly became a popular form during the silent era. It offered a chance to show off a performer’s range or for a filmmaker to explore a range of styles in one tidy package.

These films sometimes showed multiple fates that lay before a character. For example, The Eyes of Youth and The Love of Sunya, both adaptations of the same play, explored the different futures that awaited the heroine if she married each of the men who had proposed to her.

There is a great elegance to the weird or horror short story, so it is no surprise that anthologies would work particularly well with more macabre fare. Paul Leni’s Waxworks is a stylish triple feature of historic terror with a modern frame story and the tradition continued with classics like quadruple threat Black Sabbath in the sound era.

(By the way, I cannot find a definitive answer to which picture can be considered the first anthology film. The earliest reference I have yet discovered is to the 1915 release The Ivory Hand, which is described as having a scenario that “comprises three distinct stories artfully woven into one.” However, there may well be an earlier example, especially in the transition between from dramatic short films to features that was underway at the time.)

Eerie Tales was directed by Richard Oswald (most famous today for directing the legendary Conrad Veidt in the daring and subsequently banned Different from the Others) and ambitiously covers five stories, along with a frame story, featuring Veidt, Reinhold Schünzel and Anita Berber. Six roles for each of the men and five for Berber, all in the span of less than two hours. Needless to say, this picture is considerably zippier than other German releases of the period, which tended to linger.

The film opens with its frame story, a bustling bookstore with a perky owner. The shop closes for the night and three figures come to life and emerge from the paintings on the wall: the Devil (Schünzel), Death (Veidt), and the Harlot (Berber). The three make a beeline for the books (relatable motivation always a plus), toss aside the startled shopkeeper and become absorbed in reading.

The five stories they select are:

The Apparition by Anselma Heine: A woman (Berber) is being stalked by her violent ex-husband (Schünzel) and is being aided by an admirer (Veidt) but the woman disappears one night and everyone denies that she ever existed.

The Hand by Robert Liebmann: Two men (Schünzel and Veidt) are in love with a dancer (Berber) and decide to throw dice to see who will withdraw. When Schünzel loses, he strangles Veidt but is then haunted by the hands of his murdered rival.

The Black Cat by Edgar Allan Poe: A drunkard (Schünzel) is married to a beautiful woman (Berber) with a lover (Veidt). When Veidt is indiscreet in his affections, the husband murders his wife in a fit of rage and walls up her body. But something else was walled up too…

The Suicide Club by Robert Louis Stevenson: A young man (Schünzel) stumbles onto a strange club led by the President (Veidt). Members may join but never leave and the rules are simple: every week, one man draws the ace of spades and is murdered.

The Specter, an original scenario by Oswald: A husband (Veidt) with a flirtatious wife (Berber) watches as she flirts with their houseguest (Schünzel). When the husband is called away on business, the wife and houseguest see an opportunity for romance.

The Apparition is the darkest tale of the lot, with the stories growing more humorous near the end of the film. After Veidt meets Berber, she tells him of her husband’s attempts to murder her even after their divorce. The pair check into a hotel in separate rooms and Veidt goes out for an evening of drinking with his friends.

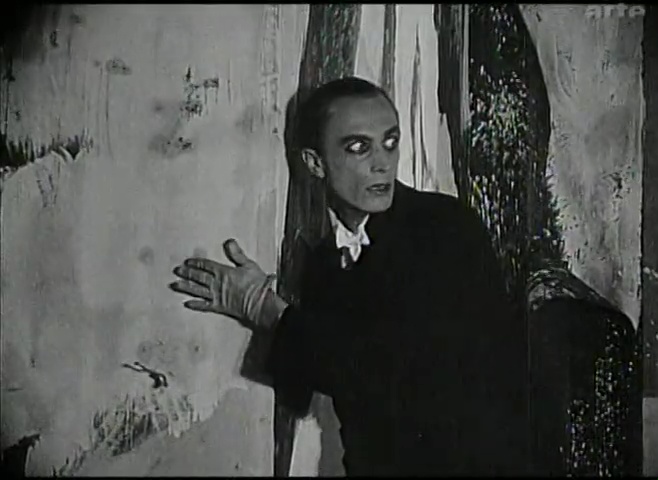

He staggers back into the hotel, the night clerk is asleep. He finds his way to Berber’s room and cannot find the lights. The full moon emerges from behind clouds and finally illuminates the room. Veidt is horrified at what he sees, the walls are splattered with expressionistic paint—blood? He screams and flees back to his room, falling into a drunken slumber.

When he awakes, he feels sure he dreamt the whole thing and goes to call on Berber. Nobody by that name. Veidt came alone. The room where Berber was staying is fresh and clean, no sign of violence and certainly no blood.

Veidt grows more alarmed as Berber’s existence is denied in every corner. The ex-husband stalks and attacks him and nobody responds. Finally, someone tells Veidt the truth: Berber died of the plague and the hotel buried her secretly and redecorated her room to cover it up. Veidt staggers off, collapses and, presumably, dies.

The original story by Anselma Heine is a bit more lyrical. Her main character never discovers why his companion disappeared and was not infected by her. Instead, he spends the rest of his life doubting what he sees with his own eyes, pursuing a study of the supernatural and seeing her, his apparition, in moments of ghostly clarity.

What seems to be a tale of terror on the surface is, in fact, an examination of faith and how beliefs can be turned on their head through the unintentional interference of others. On the surface, it may seem that Eerie Tales adopts a shallower interpretation of the material but given the bizarre behavior of the characters following Berber’s disappearance, is it possible that there is more to it?

I put forward that Veidt’s character became ill during the night of drinking with his friends and, after discovering Berber’s body and fleeing to his own room, fell into feverish hallucinations and the last part of the story is a fantasy just before his own death.

The Apparition is a strong opener with the lighting and set design building an unsettling atmosphere that does not dissipate.

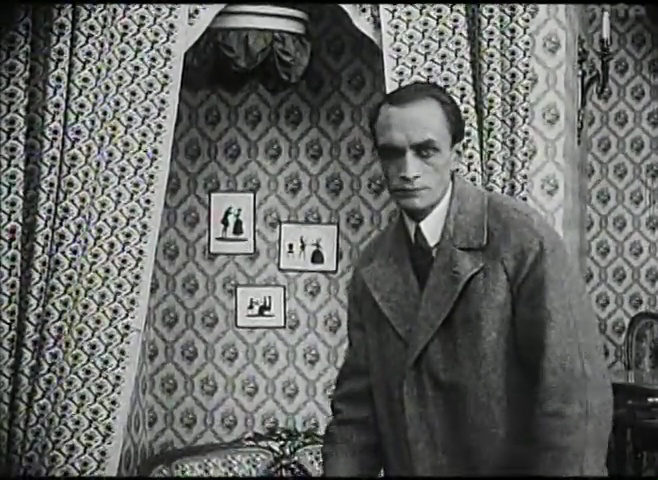

The next story, The Hand, is less ambiguous and more graphic. Both Schünzel and Veidt love Berber and decide to settle the matter like gentlemen: they will throw dice and the high roll wins the right to court her. Schünzel loses and strangles Veidt with his bare hands in a rage. The murder is never solved, Schünzel escapes and Berber continues her career as a dancer.

(By the way, Berber was an icon of the Weimar era Berlin nightlife, so the chance to see her dance—albeit clothed—is a major draw for anyone interested in this time period.)

Schünzel and Berber meet again by chance and she is delighted to renew the acquaintance but he begins to see ghostly visions of Veidt’s hand. Berber invites him to a small party and everyone decides it will be fun to hold a séance. At first, they take Schünzel’s panicked declarations of seeing someone as a party trick but, after the other guests leave, he becomes hysterical.

Berber is tired of his antics and pushes him away but then footprints appear on the ground outside the window. The apparition is corporeal. Schünzel begins to scream and flail and a figure appears behind him, strangling him, before disappearing. Schünzel is dead.

Unfortunately, I was unable to locate the original story in English, so I can only examine what appears onscreen but this is another atmospheric success, though less open to reinterpretation than The Apparition. I suppose we could consider this to be a hallucination of a man wracked with guilt but Berber does seem to see and respond to Veidt as well.

This story is also interesting because it can be seen as something of a dry run for Veidt’s body horror picture, The Hands of Orlac (later remade as Mad Love with Peter Lorre and Colin Clive), in which a pianist believes his transplanted hands have retained the personality of their original owner, a murderer. Veidt exhibits a similar acting style, giving his hands almost a life of their own.

Next, The Black Cat, which tones down the animal cruelty in Poe’s story considerably. Schünzel plays a drunkard married to Berber, while Veidt is in love with her himself. He makes the mistake of openly flirting with her before her husband and, once Veidt leaves, Schünzel takes his rage out on Berber’s black cat. She defends her pet and he kills her instead. To hide the body, he walls it up in the cellar but he isn’t able to find the cat.

Meanwhile, Veidt realizes that something terrible has happened and arrives with the police. They cannot find any sign of murder and the cellar seems empty but then…

The Poe story was written from the point of view of the murderer and he describes the sounds emanating from the wall as “a voice from within the tomb! — by a cry, at first muffled and broken, like the sobbing of a child, and then quickly swelling into one long, loud, and continuous scream, utterly anomalous and inhuman — a howl — a wailing shriek, half of horror and half of triumph, such as might have arisen only out of hell, conjointly from the throats of the dammed in their agony and of the demons that exult in the damnation.”

The cat was inadvertently walled up with the body and its cries condemn the killer. That’s a whole lot of noise to convey in a silent movie and the 1927 adaptation of Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher used special effects and animated title cards to silently portray the sounds of that story. In the case of Eerie Tales, Oswald ignores the sound and simply has the cat burrow its way out of the wall as the mortar has not yet set. This is a bit disappointing, especially since the previous two tales had been so visually compelling.

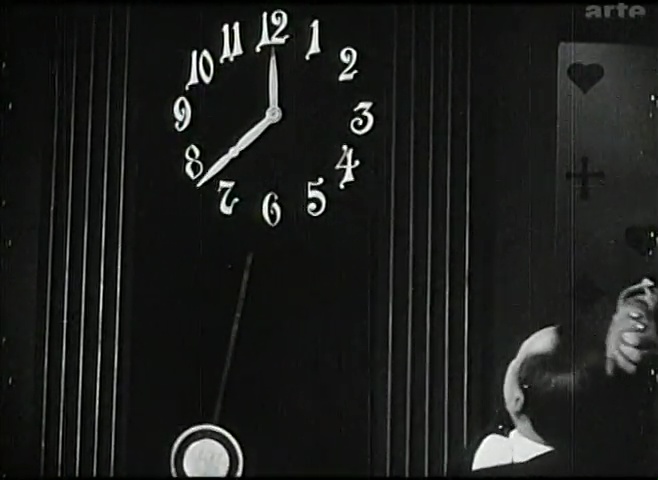

The next tale is The Suicide Club, a rather creepy and striking story cycle from Robert Louis Stevenson that I quite like. This time, Schünzel is finally the hero and Veidt the villain. Schünzel finds himself an accidental member of the Suicide Club, of which Veidt is president. The club rules are simple: every week, the members draw cards and whoever draws the ace of spades will die before midnight.

Schünzel draws the fatal card and the other members leave. Veidt uses a button to lock Schünzel in a high tech chair and boasts that if he pushes a second button, he will be killed instantly. Veidt frees Schünzel and leaves through a secret passage in the clock. It’s just a few minutes to midnight and Schünzel panics. In his fear, he tries to set the clock back but it corrects itself. Finally, he clutches his chest and suffers a fatal heart attack.

Veidt returns to gloat but… surprise! Schünzel is alive and he locks Veidt in his own chair. You see, Schünzel is actually a policeman and he toys with Veidt for a bit before leaving through the secret passageway himself.

This is a considerable departure from the book, which delves more deeply into the motives of the club members and the international manhunt to catch the president of the club. That said, I am not angry with this extremely abbreviated version with its plot twist. It’s a fresh change from the rather dark material the preceded it. Schünzel’s panache as he transforms from a panicked victim to a cool and collected detective is also highly entertaining.

I should also note that in the anthology film Waxworks, Conrad Veidt plays Ivan the Terrible. Believing he has been poisoned with a time release toxin, the tsar obsessively turns an hourglass to reset the timer and prevent his own death. This is similar to Schünzel’s “panicked” clock tinkering in The Suicide Club and I am not sure if one influenced the other or if they were both drawing from a common source.

The anthology ends on a lighter note with The Specter, in which Schünzel plays a braggart knight who attempts to get between married couple Veidt and Berber in a rococo setting. The costuming of this chapter is particularly excellent, with the powdered wigs and exaggerated silhouettes supporting the intentionally exaggerated performances of the cast.

Veidt knows that Berber and Schünzel are flirting but seems rather serene about it. A bit too serene. When he declares that he must leave for a time, Schünzel takes the opportunity to woo Berber. He brags about his bravery as a duelist and how nothing can ever frighten him. He also asks Berber to help him sheathe his sword.

But then the pictures begin to move on their own, the chandelier drops and hooded figures appear in the darkness. The knight flees in terror, leaving Berber to her fate. Which is her husband, who has been behind all of these antics. The couple finds this to be quite humorous and they embrace.

Given the depths of nastiness plumbed when sexual jealousy is in play in earlier chapters, this happy ending feels a bit hollow. I am not sure if Oswald intended this or if it was accidental. Perhaps the sumptuous costumes were meant to convey the emptiness of the reconciliation and all of this was merely a prelude to more… eerie tales. I cannot imagine that Oswald put in a happy ending to his last story because he was concerned about offending his audience. He was the director of Different from the Others and Prostitution, for heaven’s sake.

Their five tales read, the three figures return to their paintings. Just in time, as the shop owner returns with the police but all they find in the shop are books and those portraits. After the police leave, the Devil playfully blows smoke at the shop owner. This won’t be the last time they indulge in reading at night, I’ll wager.

Eerie Tales is not generally included in the pantheon of German silent horror, with the acting particularly singled out as overdramatic. I should point out that German films in general tended to use a more emphatic acting style than their American counterparts. I am not sure if this can be considered a flaw in this context, especially considering the extremely stylized performances found in Nosferatu and Metropolis. Love it or hate it but it was very much normal for the time and place.

More than normal, in fact. Reviews were enthusiastic with both stories and performances lavishly praised. Illustrierter Filmkurier reported that the theater screening the picture had been swarming for three weeks and the police had to be called in for crowd control.

I’ve covered my thoughts on the individual chapters, so let’s discuss the package as a whole. As far as delivering on its promise, the film succeeds. We were promised five eerie tales and five eerie tales were delivered. Like all anthologies, there is a shift in tone and some chapters are stronger than others but overall, the package succeeds.

Oswald was not quite the visual dynamo compared to his contemporaries but there are some wonderful moments of terror, particularly in the first chapter. The cinematography by Carl Hoffman is a bit awkward with some jerky pans but it generally looks good. I think that viewers tend to judge all Weimar cinema against titles like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and expect a lot of stylization but Eerie Tales compares favorably with other titles of the era.

The stories invite speculation and alternative interpretation, which I enjoy very much. Symbolism that is carefully explained and spelled out is all well and good but it’s fun to chew on a more ambiguous material, seeing how many ways the symbols can be interpreted.

Finally, the cast seems to be having a ball with their macabre characters, gleefully killing and being killed by one another. Oswald was famous (infamous?) for his rapid production turnaround and his audacious choice of topics, mining a similar vein to the Danish vice filmmakers and the American “sanitary” pictures. From his surviving work, it seems that he relied heavily on the charms of his cast and his instincts were correct for this picture.

One flaw of atmospheric pictures of this era was a tendency to fall into pretentiousness but Oswald didn’t have time to put on airs and the quick and dirty tone of the picture works wonders for it, as does its filled-to-the-bursting plots. It’s a long film but not an ounce of fat to be found.

I thoroughly enjoyed Eerie Tales and not just for Veidt, though he is obviously a powerful incentive to watch this picture. I liked its brisk pace, the changes in tone intrinsic to the anthology genre, the enthusiasm of the cast and some of the genuinely disturbing imagery. In fact, I think I may like it more than some of the more famous horror classics.

Where can I see it?

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

I am very much not a horror fan, and I don’t think I’ll be seeking any of these out, but I greatly enjoyed reading about them (even if I did have to turn on some extra lights!). Good stuff!

Karen

Aw, thanks so much!

Sorry if I missed this info in your thorough review but does this German DVD edition have English subtitles? Thanks, D.

No worries! No, it doesn’t.