When a French marquis discovers that his brother has become entangled with a dancer, he attempts to break them up only to fall for her himself. Disowned by his family, he turns to the movies as a profession but scandal leads to his downfall.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of Henri.

Studio on the run

While most movie fans are familiar with the innovative productions of Soviet filmmakers, the Russian film industry had been in full swing since the late 1900s and had its own studios, stars and directors. As the 1917 revolution spread, a large portion of the industry relocated to Yalta (modern Ukraine) for safety. When it became clear that even Yalta was no longer safe, they fled again, this time for France by way of Turkey.

And here is where A Narrow Escape enters the story. The filmmakers had never stopped shooting movies throughout the civil unrest and A Narrow Escape was conceived and filmed on the run. While tales of its production have improved with age (as is often the case with early film narratives), even the most basic version of its behind the scenes tale is one for the ages.

Once they arrived in France, these emigres would go on to form Films Albatros and produced a string of hits that combined the sensibilities and taste of Eastern and Western Europe but before they could do that, they needed money. They released their old films but that could only last so long and new productions were needed. A Narrow Escape combined a brief sequence shot in Constantinople (not Istanbul—yet) with footage shot in Marseilles to create the kind of high society melodrama that had been so popular with pre-revolution audiences and act as an introduction to their new clientele.

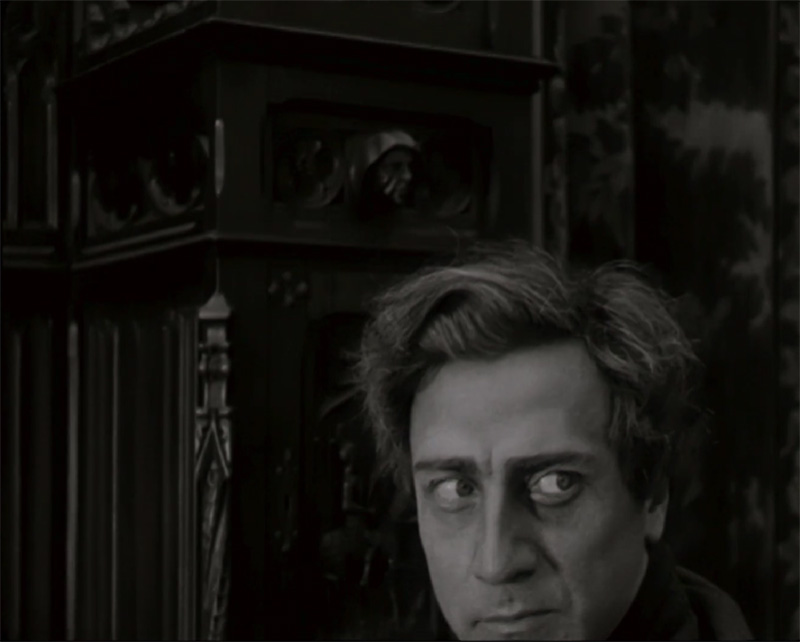

A Narrow Escape was a showcase for the biggest names in the group: Ivan Mosjoukine, versatile matinee idol, Nathalie Lissenko, tragedienne and vampire, and director Yakov Protazanov under the banner of Joseph Ermolieff.

The film centers on Octave de Granier, the pampered younger son of a titled family in Marseilles. When he discovers that his older brother has been stepping out on his fiancée with the famous dancer and actress Yvonne Lelys (Nathalie Lissenko). Octave drags his brother home to his future wife but Yvonne will not give up and keeps sending letters. Infuriated by her insolence, Octave storms to her home and tries to pay her off. She refuses the money and he finds himself falling for her.

Yvonne has a film contract in Paris waiting for her but wants to go on a vacation in Constantinople before she gets to work. She invites Octave to accompany her and, naturally, pay her way. Octave has no money of his own and his father refuses to pay for his son’s mysterious new expense. Unwilling to give up on Yvonne, Octave leaves a note and sneaks away to the ship.

Once in Constantinople, Octave can only afford a cheap hotel and Yvonne refuses to share a room without a ring. Octave solves their short-term problem by proposing marriage and the pair depart for Paris but it soon becomes clear that prolonging their fling was a mistake. Yvonne loves to flirt with her colleagues while Octave is jealous. She is paying the bills, which makes him feel inadequate. Octave enters films himself and becomes more popular than his wife, now it is her turn to be jealous. The pair can’t even stop bickering after their daughter is born. They certainly can’t stop bickering when a scandal spoils their film careers and Yvonne turns to drink.

Will Octave and Yvonne find happiness or at least end their misery? See A Narrow Escape to find out!

So, as you can probably tell, things get heavy in this film. What is more difficult to convey is the rather odd tonal shifts that occur throughout. Plenty of pictures start light and then go dark, that’s not really an issue. The oddity in A Narrow Escape is the shift from goofy society comedy, intentionally artificial, to grim and gritty social drama with no particular narrative purpose. It doesn’t portray a downfall so much as feel like two totally different films were smashed together and made to fit. Maybe that was actually the case, given the somewhat chaotic and rushed production.

With that in mind, it is surprising that the picture works as well as it does and a good deal of credit belongs to stars Mosjoukine and Lissenko. Their characters are spoiled, selfish and, at times, deeply unlikeable. Both actors manage to convey charm but also the tragedy of one impulsive decision ruining many lives. Lissenko has a particularly fine scene later in the film in which her character has been forced to take a dancing job at a dive. She sits there drinking her sorrows when an older woman, clearly an alcoholic, tells her that she was once beautiful too. Lissenko is horrified at seeing her future but still cannot resist another drink. The wordless transition from shock to fear to flippant disregard is quite lovely.

Mosjoukine was always a force of nature and he could overplay a bit if not directed carefully but even his overplaying is magnetic to watch. He does fall into it here, especially in the beginning, but quickly finds his feet in the role of Octave. Mosjoukine worked well in a variety of genres, from comedy to action-adventure, but he was at his best with intense brooding and he gets plenty of that in the final act of the picture.

I should clarify that, while Eastern European audiences did have a greater hunger for tragedy than their western counterparts, pre-revolution Russian productions were not devoid of humor. For example, The House in Kolomna (1913), starring Mosjoukine, is a saucy sex farce and he clearly relishes his role as a cross-dressing lover attempting to sneak into his girlfriend’s home under the nose of her protective mother. Comedies like The Cameraman’s Revenge and Antosha Ruined by a Corset found their humor in a similar vein. (And, it should be mentioned, relied on Polish talent.)

So, the lighter sequences in A Narrow Escape may have been intended to appeal to Latin sensibilities but they were also very much within the comfort zone of the Ermolieff acting troupe. That said, Protazanov’s pre-revolution body of work is heavy stuff indeed and he clearly was more at home with the darker turn of the film’s second half. (I hesitate to state definitively that Protazanov never made a comedy pre-1920 because so much of his work from this period is lost or inaccessible. In any case, I have never seen one.)

Whether or not the ending (spoiler: it was all a dream) was intended to soften the blow of the film for the new audience is something that I wonder about. You see, Russian films under the tsar could be dark stuff indeed and ending the film with Octave on the gallows would not have been odd. Pre-revolution films often preached against marrying outside of one’s class. Or within one’s class. Just to be safe, never get involved with anyone at all. However, Protazanov returned to Russia and made a little film called Aelita, which, you guessed it, also ended with it all being a dream.

Obviously, Soviet filmmaking was a totally different beast with different overlords and political intentions but it would be a mistake to fall back on the old East = Tragedy, West = Happy Ending trope. Hollywood made some tragedies and Eastern European films could have happy endings.

That said, A Narrow Escape is at its best when its characters are at rock bottom. Star-crossed lovers ending up together across a class divide are a cinema staple but, it could be argued, the most interesting part about such a match is not the happily ever after but how they deal with their differences after they defiantly pursue love. Cecil B. DeMille examined this in The Golden Chance and Saturday Night (early DeMille is considerably grittier than most viewers might imagine).

Octave and Yvonne impulsively get married because they have a bad hotel in Constantinople. Their passion quickly fades but they are stuck with one another, no fight bad enough to warrant a permanent separation but they are not happy. With no relief in sight, they turn to unhealthy coping strategies and sink deeper into self-destructive behavior. In other words, an incredibly realistic portrait of a hopeless marriage. And Mosjoukine and Lissenko sell it with their impeccably-tuned performances.

Unfortunately, this stronger sequence feels rushed because we have had four reels of preamble. Not to say that the start of the picture is wholly without merit but it can be rough going. The story does not flow smoothly but it’s also not intentionally weird enough to keep the viewer’s attention. We are not invested in the romantic antics of Octave’s brother because we know nothing about him or his fiancée. It’s a big ask to request that viewers stick it out for forty-five minutes to get to the good stuff.

It bears repeating that this picture was made under incredibly trying circumstances and heavy pressure. The Albatros crew would later pull off a genre hat trick with ease in The House of Mystery, a heady serial with comedy, romance, melodrama, action, cliffhanger serial sequences and murder. A Narrow Escape can be seen more as a dry run for their later successes.

So, how is the film overall? Basically, I don’t believe that The Narrow Escape is going to appeal to anyone who isn’t deeply interested in the silent era Russian film industry in exile. That said, I also don’t believe that this film is going to be sought out by anyone who isn’t already interested in the Russian film industry in exile. In short, the people likely to see this film and the people likely the appreciate it are one and the same.

Is A Narrow Escape a good movie in its own right? Well, it has its moments but the entire package is flawed. That being said, it is astonishing what the future Albatros studio was able to accomplish under incredibly trying circumstances and the moments of brilliance make this picture well worth seeing.

If you’re interested enough to see this film at all, you will probably find something to enjoy, particularly in the stronger second half. It’s a valuable piece of film history that is available to the general public at last and that is worth celebrating.

Where can I see it?

Stream for free with French and English bilingual intertitles courtesy of Henri.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.