The outlook wasn’t brilliant for the Mudville nine that day… but then they decided to do something about it and attack the umpire. Extremely loose adaptation of the famous poem.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Strike Out

Casey at the Bat doesn’t need an introduction to most American readers, the poem is a classroom staple and a pop culture icon. The story of a losing team’s star player arrogantly refusing to swing at two pitches (“That ain’t my style”) before missing the third struck the country’s fancy when it was published in 1888 and the poem hasn’t been out of the public eye since.

That year was, of course, part of the history of pre-cinema/early cinema and it was inevitable the mighty Casey would appear on the silver screen sooner rather than later. Sure enough, the Edison company shot their own baseball picture at Thomas Edison’s New Jersey estate.

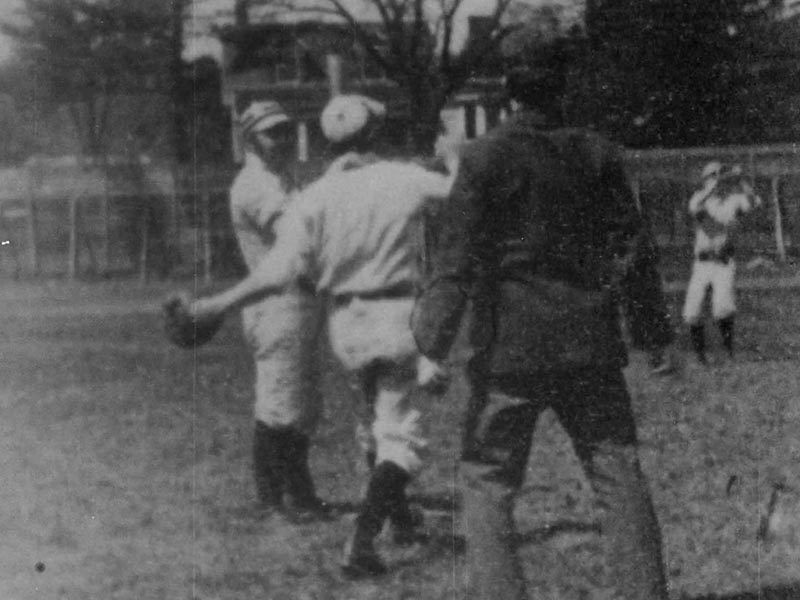

The film doesn’t cover the entire poem. At about thirty seconds, there isn’t enough time to even adapt a stanza. In fact, descriptions of the film as “loosely adapted” from the Ernest Thayer poem are generous, to say the least.

Casey at the Bat is shot from behind home plate by director James H. White and shows mighty Casey swinging at the ball but frustrated by the umpire’s calls. Finally, he has had enough and kicks the ump’s legs out from under him before attempting to throttle the man. Spectators jump into the fray and the film ends with the brawl still well underway.

If you will recall, in the poem, after Casey’s first and second strikes, the crowd calls out, “Kill the umpire!” and “Fraud!” but is calmed and silenced by the confident Casey. The third and final strike is not depicted, instead, the poem describes the despair of Mudville before delivering its punchline: “Mighty Casey has struck out.” No umpires were killed in the making of this poem.

There are a few ways to interpret the film in the context of the ubiquitous and popular poem. The first possibility and probably the most likely is that the Edison team wanted to make a baseball picture portraying much-hated umpires getting their comeuppance. The original entry in Edison’s 1900 trade catalog says that the film serves as a “warning to all unfair umpires.” The Casey name was merely slapped on to help market the picture.

Another possibility is that Edison’s team remembered the “Kill the umpire!” line from the poem and decided to make a film around that idea, not really bothering to check back with the source material to see if it accurately reflected the spirit of the work.

The third possibility and probably the most interesting is that the Edison team was familiar with the poem, understood what it was about and wanted to give Casey a bit of revenge for the way he was treated. Now, obviously, the point of the poem is that Casey brought his fate upon himself by refusing to try his best with the first two pitches but this has never stopped creatives from attempting to give him a redemption arc. (Though, if you want to argue that the poem was actually a parody of the high expectations put upon athletes and the way they are portrayed as lazy if they fail to secure victory, I am certainly willing to listen.)

There were at least two poetry sequels featuring Casey hitting the ball when it mattered most and reclaiming his reputation. They’re not particularly satisfying; sequel songs and poems rarely are—after all, we listen to It’s My Party and not Judy’s Turn to Cry for a reason—but they reflect a compulsion to say more when, really, everything has been said.

The lost 1916 film adaptation of the poem, starring De Wolf Hopper (more on him in a bit) takes a similar stance, portraying Casey not as an arrogant local hero done in by hubris but a nice fellow who burns his batting hands putting out a fire and missing because he’s worried about his injured niece. Hollywood, known for missing points in source material, has rarely struck out so spectacularly. I would love to see the picture just to find out for myself if this schmaltz actually worked on any level.

My point in all this is that Casey at the Bat’s beauty is in its direct simplicity. It’s a mock-heroic epic that ribs sports culture, sports idols, sports fans and the danger of complacency. These are all timeless topics and we are given just enough detail to paint a picture of Mudville, Casey and the passionate fans. Explaining away Casey’s hubris with hokum or trying to make it all better retroactively with a sequel deflates the original work. Was this the intention of the Edison team when they made their 1899 film? We will probably never know but it’s a possibility given the history of Casey.

This leads us to another common line of discussion: Who was Casey? Multiple baseball players have been identified as the inspiration but that topic has been covered by baseball historians far more familiar with the game than I am. I am inclined to believe Thayer in his claims that Casey was nobody in particular.

However, Casey had a life in American pop culture beyond the poem and its adaptations and these are extremely interesting in understanding the rise of multimedia content in the Gilded Age.

De Wolf Hopper, mentioned earlier, was intimately connected with the poem and his tongue-in-cheek stentorian recitations were crucial in its popularity. His fans included Theadore Roosevelt, who invited the comedian to present his recitation at a private White House performance. Hopper’s version was an old school sort of affair. He raised his eyes heavenward, described Mudville’s antics in plummy tones and trilled his Rs as he told the tragic tale of Casey’s downfall. He was filmed with synchronized sound in 1922 for the DeForest Phonofilm company, an experimental sound-on-film concern.

By this time, Hopper had been reciting the poem for over three decades but there was a rival Casey in the 1890s, recording superstar Russell Hunting. While Hopper approached Casey with great gravity and mock grandeur, Hunting adopted an Irish accent. (Casey, along with Kelly and Clancy, were go-to Irish names in fiction at the time.) Ethnic humor was wildly popular, with comedians affecting Irish, Dutch, and Yiddish accents, among others, as part of their regular schtick.

Hunting took advantage of the new wax cylinder technology to become a recorded comedy superstar. His rendition of Casey at the Bat was marketed alongside an expansive Casey series featuring the Irishman at odds with America. Hunting’s Casey character tried his hand at medicine, took down census answers, and even became a Rough Rider. Hunting performed all the characters himself and his impressions were praised but, honestly, they really do sound like the same guy putting on different accents. His real strength lay in his ability to switch back and forth between characters at a rapid pace.

I should note that some sources erroneously claim that Hunting’s hit recording of Casey at the Bat was a musical rendition. In fact, spoken word recordings were immensely popular and covered genres ranging from poetry to true crime. A humorous story from the era told the tale of a minister who recorded his sermon on wax while away on vacation, only to have a practical joker replace it with an obscene comedy recording. A hot time was had in church before the deacon figured out how to turn off playback.

Also, there were numerous Casey ethnic comedy series being produced and these spilled over into the movies. It’s a massive topic and I will be digging into it at a later date but we’re already in the weeds, so let’s head back to baseball.

Casey at the Bat was also, naturally, given audiovisual presentations outside of motion pictures. Slideshows were the de facto form of projected entertainment when it had first been published and “illustrated” renditions of Casey were proving to be popular. So, the Edison film may have been the first time Casey at the Bat was (kind of) adapted for cinema but it was also part of a cultural wave that saw many uses for the mighty baseball player.

Casey at the Bat is a simple comedy featuring stereotypical slapstick violence but digging a little deeper into historical context is quite rewarding. Maybe it was an attempt to avenge Casey, maybe it was just a bit of fun location filming. Whatever it was intended to be, it is a fascinating look into the past.

Where can I see it?

Stream for free courtesy of the Library of Congress.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Really enjoyed this first-rate post — interesting and informative. I learned so much! I’d heard the name “Casey at the Bat,” but I never really knew much about it. But I do now!

— Karen

Thank you so much!

Hi Fritzi. What a nice writeup. I always take pride that it was originally published in the San Francisco Examiner. Have you ever heard of this real life kill the umpire story? https://x.com/baseballinpix/status/1729684678146146603?s=20

Thanks, I will check it out!