The remaining frames of the earliest known Shakespeare film adaptation, this picture boasts the performance of Sir Herbert Beerbahm Tree and was one of many productions designed to add a touch of class to the infant industry.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the BFI.

How to Recognise Different Types of Trees from Quite a Long Way Away

As the nineteenth century drew to a close, the film industry was enjoying a period of financial success and technical advancement. And length. The days of peepshow quickies (double entendre intended) weren’t over but there were longer productions in town.

The full-length feature film had been pioneered in 1897 as a way of recording boxing matches, Siegmund Lubin’s 1898 Passion Play was a series of short pictures that ran over an hour when played back to back and even longer if we factor in the color slides and lecture materials that were sold as a package along with the movies, making it a multimedia event.

But outside of religion and pugilism, mainstream productions were kept to a tidy runtime of five minutes or so, though sequels could be run sequentially (see The Dreyfus Affair for an example). Still, filmmakers had more time than ever to tell their stories and they were growing ever more ambitious.

Shakespeare on the screen was inevitable. A major portion of most film companies’ catalogs was dedicated to making popular stage entertainment normally available only to residents of London, New York, Paris or Berlin available to the masses. From serpentine dances to wild west shows to, yes, even more boxers, geography was no longer a limitation. (Subject to local censorship laws, of course.)

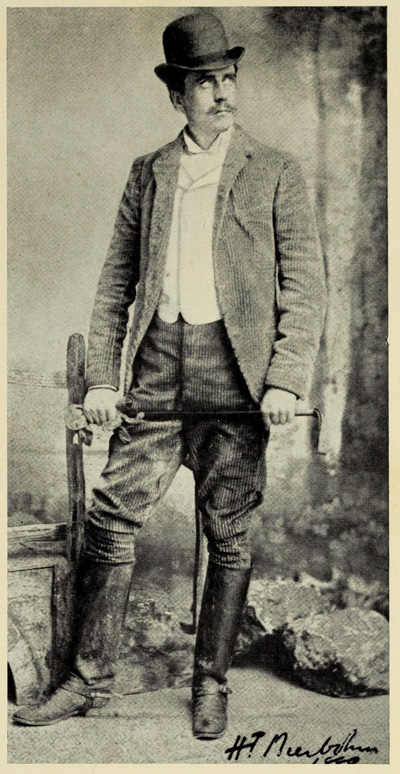

No English language plays have cachet to match Shakespeare and so, in 1899, the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company partnered with Herbert Beerbohm Tree, top Shakespearean, to perform some scenes from King John before the camera.

As was usual for filmmakers of this era, William K. Dickson and Walter Pfeffer Dando were working from the assumption that the audience had at least a passing familiarity with the source material and were basically out to create a “good parts” version. It’s often listed as the first Shakespeare film but so much from this era is lost that I hesitate to be decisive, so let’s at least call it the “earliest surviving.”

The film had been originally made up of four parts, including the signing of the Magna Carta, but all that remains of the film is the climactic death scene with a poisoned King John writhing for about a minute while reciting dialogue.

(He is, of course, Prince John of Robin Hood fame but always King John in Magna Carta-ish matters, as is chronologically correct, however, the connection is politely ignored in Hollywood Sherwood Forest fare. It’s similar to how Puritans are referred to as Pilgrims for all American holiday applications. Historical dual branding is a fascinating topic.)

Due to the film being featured on Horrible Histories, quite a few people unfamiliar with early movies have commented on it. One question often asked is what Tree is saying in the film. He is likely reciting John’s final dialogue from the play, at least that’s what my rudimentary lipreading skills tell me and what matches the action onscreen.

The other question was whether or not the “page” character (actually Prince Henry) was played by a woman and he was. Dora Senior took on the trouser role, a very common practice at the time, lest the lead juvenile’s voice break mid-season.

Tree’s, shall we say, overbuttered performance in the film has been a subject of mockery for modern viewers and is sometimes blamed on the fact that King John was silent. “Oh, silent movie people frequently overacted to compensate for a lack of dialogue” is a pretty common opinion. In fact, Tree was pretty infamous for not regulating his stage acting to the needs of the screen. If anything, stage tradition of the era is to blame more than any film acting technique, which was in its infancy and based heavily on theater anyway.

While it is important to remember that stage acting of the era was very much focused on playing to the whole house and broader gestures were the norm, it is equally important to know that some Victorians felt that Tree did indeed tend to lay it on a bit thick.

According to Writers, Readers, and Reputations: Literary Life in Britain 1870-1918 by Philip Waller, Tree’s production of King John was being performed when the Boer War was declared and this news sent the actor into throes of patriotic hamminess. Anti-imperialist poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was in attendance and described Tree’s performance as “egregious” and “a violent piece of ranting.” Tree was also criticized by more mainstream figures for his propensity to take liberties with the classics. However, he was also widely praised for his acting skills, so there was by no means a huge anti-Tree movement.

It is difficult for us to judge Tree’s performance fairly because only part of the last and broadest scene survives. (Death scenes have always been an invitation for actors to go all out.) A few frames survive but they only give us the vaguest hint as to the quality of the production.

After his early brush with cinema, Tree would continue to allow his productions to be filmed. The Tempest (1905) was a stage production featuring Tree and was purchased by distributor George Kleine, who specialized in bringing foreign fare to American audiences under his own banner. Henry VIII (1911) was likewise a filmed stage production. Tree’s Trilby likewise made it to the screen.

Tree also chimed in on a brewing stage vs screen controversy in 1912: whether or not motion picture theaters should be allowed to be open on Sunday. Being an American, I automatically assumed this was a religious issue but the primary arguments were, in fact, secular. Sunday was the traditional day off for British music hall and theater performers and if movies were playing, live theater management would be pressured to match the convenient weekend hours and rob their performers of much-needed rest. Tree argued that music halls and movie theaters should have identical rules of operation.

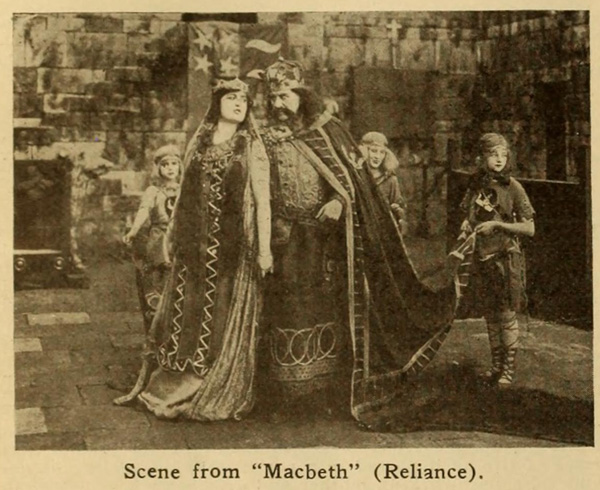

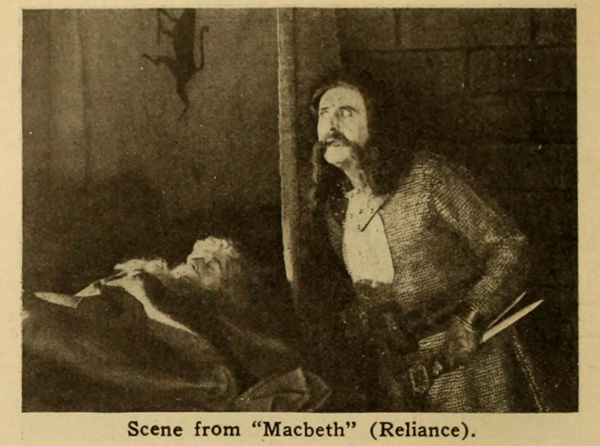

By this point, movies were clearly no passing fad and Tree became more serious about using the medium to preserve his legacy. In 1915, he traveled to the United States in order to do just that. Tree had been knighted a few years earlier and Americans have never met a title they didn’t like, so SIR this and SIR that was all over the trade press. Tree made an adaptation of Macbeth (apparently failing to understand that some of the speeches would have to be cut) under the direction of John Emerson in 1916 for the Triangle company.

Triangle crowed in the industry press about its success in introducing Tree to the screen (then as now, you simply cannot trust company press releases) and heavily marketed Macbeth as a new kind of prestige production. The film is unfortunately lost, so we cannot properly judge it but the stills are promising (though I cannot say that I think much of Emerson’s abilities as a director). Here’s hoping that at least some of it will turn up eventually. His more modern follow-up vehicle, The Old Folks at Home, is likewise lost.

There was enthusiastic chatter about more film roles to come but they did not materialize. Tree returned to England and passed away in 1917. His dreams of immortality did come true, just not with the production he expected. King John will likely always have the “first Shakespeare movie” attached to it no matter what turns up and Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s performance in it will be the one he is judged by.

All film is a time capsule of some sort but King John seems particularly distinct to its culture, nation and time. We will never really experience a Tree performance—anyone who saw him perform in life is long dead and all we have are reviews, descriptions, a few sound recordings and King John.

Where can I see it?

Stream for free courtesy of the British Film Institute and the EYE Filmmuseum.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.