When a musician moves into his new flat, he can’t resist inaugurating the place with an enthusiastic performance of the new smash hit Alexander’s Ragtime Band. The song is so catchy that it causes havoc across the building.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of EYE.

The bestest band what am

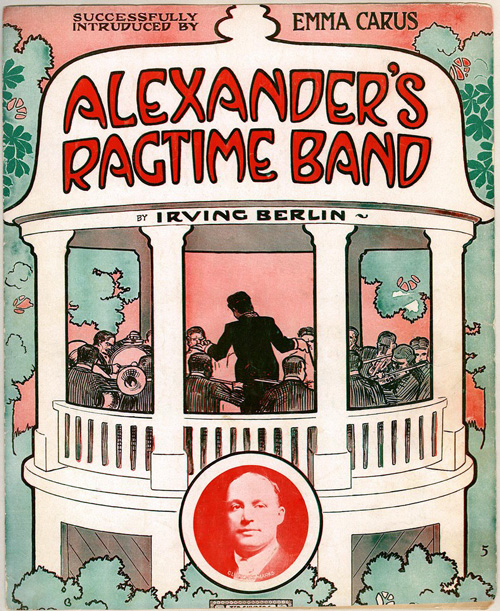

Irving Berlin became a superstar songman with Alexander’s Ragtime Band, which was not actually ragtime but nevertheless has been inextricably linked to the genre ever since. Naturally, the movie industry was keeping a close eye on trends that could be adapted to the cinema and who could resist a good old-fashioned bit of infectious music?

Oh, You Ragtime! was made by the American arm of the French Éclair company and its plot is simple but effective: A musician is moving into a new flat and is very fussy about the care and location of his beautiful piano. (The fact that the musician looks very much like someone who lives on a hill in Los Angeles and would later have an instrument delivered by Mr. Laurel and Mr. Hardy adds to the film’s charm retroactively.)

The musician can’t even wait for the movers to finish setting up his furniture, once the piano is in place, he sits at the keyboard, gloats over his sheet music for Irving Berlin’s Alexander’s Ragtime Band and begins to play. The movers can’t help but sway to the music, twirling rugs and chairs, until the musician becomes annoyed and shouts for them to leave.

Alone again, the musician continues to play but this time, his music takes over a millinery workshop and the young women follow the tune up to his flat and begin to dance. Their supervisor arrives but she is as infatuated with the music as they are and joins in.

The music continues to spread. The movers return and bring along a pageboy, a professional office is emptied as the stenographer, secretary and boss all fall under the spell of the musician’s song. The entire group dances until they collapse.

The musician finishes playing and is angry to see his apartment filled with sleeping strangers. The surviving footage ends here but Moving Picture World states that in the original ending, the musician switches to playing a quick-step and drives everyone back to work again. Apparently, special effects were used to portray the crowd returning to their duties and the scene is described as the highlight of the film. A pity the footage seems to be lost.

Well, that was fun! The gag wasn’t new when the film was released in 1912 and the Moving Picture World review compared it to The Pied Piper of Hamelin but the execution is quite charming. The cast has fun with their roles, swaying and spinning to the music.

Irving Berlin had scored a mammoth hit with Alexander’s Ragtime Band the previous year and its unshakable popularity had just begun. It’s easy to see why the song was chosen as the centerpiece of this comedy: it was literally everywhere.

And this leads to quite a few questions about silent film music. Mainly, how did theaters handle fresh hits that were very much under copyright?

(I am greatly indebted to the excellent Silent Film Sound by Rick Altman, who carefully cataloged the music and spoken word performances that accompanied films in their earliest days. Highly recommended reading for anyone who is interested in the many, many ways silent films were not actually silent.)

The film would have been accompanied by live music when it was initially released— larger theaters quickly learned that quality music was a draw and smaller houses had to at least offer something, even if it was just the church piano. In Oh, You Ragtime! the sheet music was carefully displayed onscreen, so the picture was practically screaming for the accompanist to follow the onscreen pianist’s lead and bang out some Irving Berlin.

In fact, this would have been standard operating procedure as the nickelodeon picture show had embraced song slides and accompanying singalongs as part of the entertainment. Theater owners had every motivation to do so. It padded out the show, encouraged audience participation and allowed the theater to bask in the reflected glow of big pop music hits. Good music and good fun were the best way to differentiate theaters that all had access to essentially the same pool of films.

This was met with a mixed critical response as musicians tended to play the hits and sometimes didn’t really seem to bother with matching the action on the screen. This caused issues if, say, the violinist went into a jaunty rendition of I’ve Got a Pain in My Sawdust or Yip-I-Addy-I-Ay! as the heroine lay dying on the screen. But, for the most part, what the people wanted the people got and they wanted I Love My Wife; But, Oh, You Kid!

This leads me to an important question, though: would the music for such a film as Oh, You Ragtime! have been licensed or would it have been played on the sly, hoping that nobody would notice a copyrighted hit being played in Literberry, Illinois, population 17.

The answer is a bit more complicated but it comes down to a problem that we are still dealing with today: the American court system has never been quick to grasp the implications of new technology and is even slower to figure out how, exactly, it would be used.

I already covered the chaotic world of copyright law of the nickelodeon era in my review of the off-brand 1907 Kalem version of Ben-Hur but the short version is that courts were not entirely sure that movies were really adaptations of books because they were not the spoken stage. Kalem took advantage of this ambiguity to release a film that drew from both the bestselling novel and the hit stage adaptation. Lew Wallace, the novel’s author, had been protective of his copyright to a Disney degree and his estate sued Kalem. The Ben-Hur case wended its way through the courts and in 1911, the United States Supreme Court found in favor of the Wallace estate which settled the matter of film adaptations at last.

So, where did that leave the playing of pop music in movie theaters? Well, around the same time the Ben-Hur case was playing out, the music industry was exploring its legal options to deal with unauthorized use of copyrighted works, from player pianos to movie theater singalongs.

Keep in mind, American copyright rulings during this period were bonkers and contradictory—and varied greatly by state or city. Rather hilariously, in 1908, the Supreme Court accepted a lower court’s ruling that bootleg player piano rolls were not a violation of copyright because the sheets were made to be read by machine and were not readable to the human eye. Similarly, in 1907, an Indiana judge ruled that a local movie theater was exempt from theater tax because it did not have scenery or other traditional stage equipment and was therefore not actually a theater. Movie theaters were sometimes legally classified as circuses but, well, if the shoe fits…

Many of these issues were cleared up the Copyright Act of 1909 and the subsequent amendment in 1912 that classified motion pictures as protected works in their own right, rather than being legally defined as collections of photographs, as had previously been the case.

Movie performances using hit tunes, though, were not yet resolved in American theaters. (I am very careful to state “American” because other places, particularly the UK, had their own extremely complex musical licensing rules during this period and that is another story for another time.) There were legal actions, discussions in trade journals, releases of movie music collections that did not violate copyright but no definitive resolution. Essentially, the legal defenses were that performance was not publication (laws focused on sheet music) and that music was adjacent to the main product, the movies, and was offered free of charge.

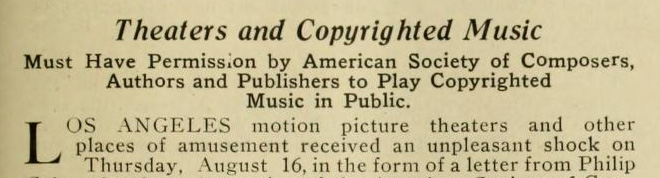

It wasn’t until 1917, five years after Oh, You Ragtime! was released, that the United States Supreme Court ruled in the case of Victor Herbert et al vs. The Shanley Company and ended any debate. The ruling affirmed that copyright holders should be compensated for the use of their property even if the venue was not solely focused on music and did not charge separately for it. (Restaurants, hotels, etc. and, of course, movie theaters.)

The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers, which had been attempting to collect licensing fees since it had been founded in 1914, immediately sent notice to movie theaters that they should apply for licensing and pay fees PDQ if they wanted to use the music of the society’s members, which included Irving Berlin. Movie theaters were to pay 10 cents per seat annually ($2.63 in modern money, as of this writing) while cabarets and restaurants paid varying flat fees. So, if you wanted to screen Oh, You Ragtime! in your 300-seat theater with its music, it would cost $30 or almost $800 in modern cash annually.

The ASCAP was ready to back up its words, too. It had spotters reporting the unauthorized performances of member music and took legal action against offenders. Legal skirmishes continued but the war had already been won.

So, that was a long way around saying that, yes, the accompanists probably played Alexander’s Ragtime Band during screenings of Oh, You Ragtime! and, no, it doesn’t look like they paid a thin dime for the privilege. In any case, the picture was hardly unique in that regard. It received good reviews at the time and was praised as zany fun.

Oh, You Ragtime! is, unfortunately, incomplete but what survives is a fun glimpse into the novelty pictures that entertained pre-WWI audiences alongside the straight comedies, the dramas and the actualities. A little bit of silliness and a hearty singalong was probably just what the doctor ordered, especially if the previous film had been a three-hanky affair.

Where can I see it?

Watch the surviving footage for free courtesy of the EYE Filmmuseum.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Nice review of a fun, sadly incomplete, one-reeler. Someone should write a jaunty score to accompany this fun film. I wonder if the filmmakers at Eclair would have seen Alice Guy’s surprisingly similar 1907 Gaumont production, LE PIANO IRRESISTIBLE (https://archive.org/details/LePianoIrresistible#). I immediately thought of the Guy film when watching OH, YOU RAGTIME! David

I think it is highly likely given that this was a French production made in America. Remakes and remixes were ubiquitous.

Very similar to Le Piano Irréstible made in France in 1907. I’m a great lover of one reel films and I enjoyed watching Oh You Ragtime! Great fun.

Many thanks for your review.

Yes, any good plot, gag or special effect worth doing once was worth remaking.