Finland’s perennially popular play made it to the movie screen half a century after its original publication. This is a countryside romance of double: pairs of courting couples, two rivals for a fortune… and a bandit and his doppelganger.

Home Media Availability: Stream for free courtesy of Elonet.

Feel my tuft!

Silent era Hollywood was an international powerhouse in the business of exporting and the world fell in love with the lavish fantasies and glamorous stars. However, no matter how funny Charlie Chaplin was, how heroic Douglas Fairbanks, how glamorous Gloria Swanson or how vivacious Mary Pickford, there was always a demand for a little something of the home vintage.

Finland, recently independent from Russia and free from an aggressive russification campaign as a result, was beginning to build up its film industry in earnest, releasing a variety of comedic and dramatic fare. While some pictures, like the documentary and sales brochure Finlandia, were meant for export, much of the material produced covered Finnish topics for a predominantly Finnish audience. (With releases in neighboring Scandinavian countries, particularly Sweden.)

And here is where The Cobblers on the Heath enters the tale. The 1864 play by Aleksis Kivi is considered a landmark of Finnish literature and, unfortunately for me, its main appeal is apparently its clever turns of phrase. I say unfortunate because I do not speak Finnish and linguistic wit is untranslatable. However, a silent film adaptation levels the playing field somewhat with its visual storytelling.

Set in the 1840s, the film covers the adventures of the residents living in a rural community. A wealthy man passes away with a strange clause in his will: enchanted with the idea of two children marrying when they come of age, he leaves a small fortune to whichever one of them marries first, with the idea it will bring them together in matrimony.

The children are Jaana (Heidi Korhonen), the daughter of a sailor, and Esko (Axel Slangus) the son of a cobbler. Jaana’s mother is dead and her father out to sea, so she has been taken in by Esko’s family. If you think that close contact would bring those young people together, you are 100% wrong.

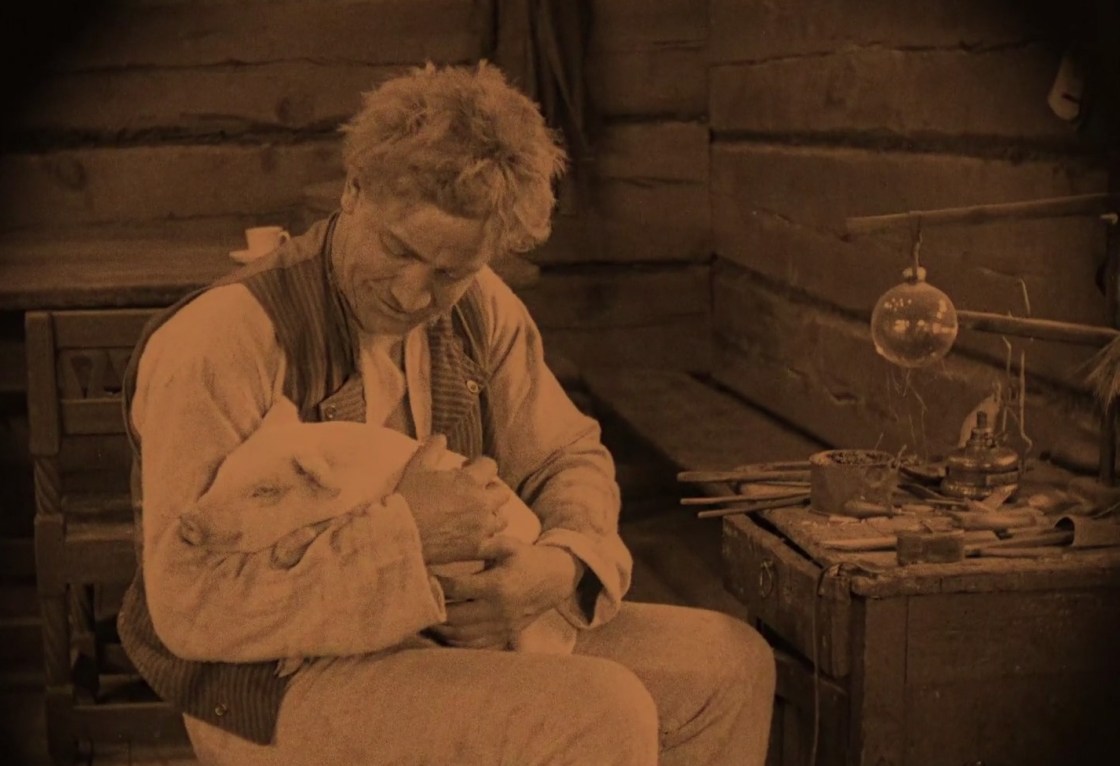

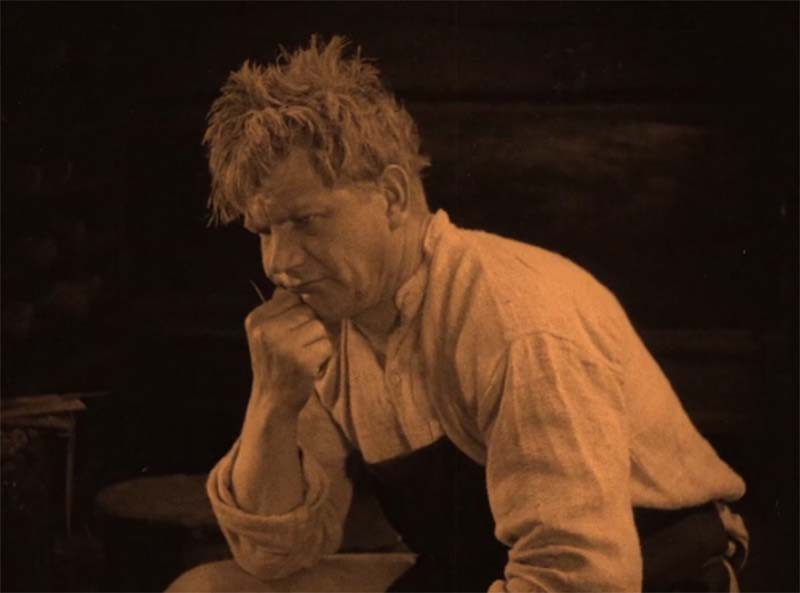

Esko, like his father Topias (Alarik Korhonen), is in no danger of splitting the atom, much to the irritation of his formidable mother, Martta (Kirsti Suonio). However, he has managed to win the hand of Kreeta (Märta Hansson) and the family is abuzz with wedding preparations, especially since his early marriage means the fortune will be theirs.

Jaana is in love with the blacksmith, Kristo (Jaakko Korhonen), but her father cannot give his blessing, so it looks like she will lose her chance at the money and must wait for her father’s return if she hopes to marry. Esko and his friend, the mischievous Mikko (Aku Käyhkö), set out on the three week journey to bring Kreeta back for the wedding. Meanwhile, Martta and Topias send their younger son, Iivari (Antero Suonio), to town to purchase supplies for the wedding feast. Both boys are told that there is a large reward for a wanted thief who can be identified by a large mole on his face.

When Esko and Mikko arrive at Kreeta’s house, they see a wedding banquet underway. The bride is Kreeta and the groom is the local clogmaker, which Esko considers a major step down from a cobbler like himself. Kreeta’s father explains that he was joking with a very drunk Topias when the latter proposed the engagement. Esko picks a fight with Teemu the wedding fiddler (Sven Relander), which he loses, and confronts Kreeta and her family before smashing up the house and fleeing with an amused Mikko following.

Since the bridal entourage is a bust, Mikko suggests visiting relatives on the way home. And by a stunning coincidence, every member of his family can be found at a public house. Meanwhile, Iivari goes carousing with his uncle Sekari (Kaarlo Kari) and drinks up the wedding budget.

In the midst of all this, Jaana’s father Niko (Juho Puls) has returned and is anxious to get back to his daughter. Overhearing Iivari and Sekari discussing their predicament and how to make up for the money they have been drinking away, Niko decides to disguise himself as the wanted thief, use soot to add a mole to his face, and trick them into giving him a ride home.

Will the ploy work? Will the real thief be caught? Will Esko ever manage to get married? See The Cobblers on the Heath to find out.

I’m going to cut right to the chase: I had a good time watching this picture. The opening is a bit slow but the pace quickly picks up when Esko and Mikko set out on their journey to claim Esko’s bride.

This picture is very much in a similar vein to the bucolic countryside films that were taking the American box office by storm. The twentieth century had started with chaos as new technologies, a world war, and a pandemic had reshaped the globe. Finland gained independence and survived a civil war, plus a brief flirtation with monarchy, which was quite enough history for a century, let alone a few years.

With all this in mind, the wild popularity of Hollywood films like Way Down East, Tol’able David and Charles Ray vehicles like The Old Swimmin’ Hole is an understandable response to chaos. The warm safety of bucolic scenery and a town of oddballs, where there is danger but it can be overcome by bravery and grit… a nice respite from a chaotic world. It’s as much a fantasy as any fairy tale but it feels real.

The Cobblers on the Heath was a warhorse of the Finnish stage by the time it made its way to the movie screen but that works to its advantage. Audiences would have been familiar with these characters and could drink down their well-known adventures like warm bowl of soup.

That’s not to say that the only thing going for The Cobblers on the Heath was the zeitgeist of the early twenties in Finland. It’s a lovely film to look at, with cinematographer Kurt Jäger lingering lovingly on forests and lakes. Screenwriter Artturi Järviluoma did a clever job of opening up the play, cutting between the adventures of Esko and Mikko and the antics of Iivari and Sakeri, as well as scenes of romance between Jaana and Kristo.

Järviluoma, Jäger and director Erkki Karu also deserve praise for their playful use of fantasies and flashbacks, which help enhance the cinematic flavor of the picture. We see Esko’s fanciful vision of his father’s biblical parable (Esko visualizes the holy land as a slightly mistier Finland, complete with top hats), Kreeta visualizing Esko as an owl, and Topias’s fantasies of his son’s happy wedding. We see Esko flash back to his humiliation at Kreeta’s wedding feast (not the speediest editing cuts but dramatic and effective) and Martta remembering her son’s childhood silliness. Top notch stuff that enhances the picture considerably.

However, and I do not necessarily consider this to be a fault in the film, there is a certain expectation of familiarity with the original play. This would have been reasonable and was present in many culture-specific films of the silent era. (See my review of The Assassination of the Duke of Guise.) For example, it was not made clear why Esko could not sign his own marriage certificate by the film’s action alone. Every film, no matter where it is made, relies on a certain amount of context and expects the audience to follow. How this context translates or ages varies in every case. For example, some American films made in the 1980s treat sushi, lattes and arugula as hopelessly exotic instead of the everyday supermarket fare they are today.

All this being said, much of the antics found in The Cobblers of the Heath are pretty universal. A troublemaker of a friend like Mikko? We all know one of those. An eccentric clause in a will causing all sorts of chaos? A comedy staple worldwide. A teenage boy trying to get out of trouble through means of a zany scheme? Where would movies be without that particular trope?

As for the cultural aspects, it is pretty clear from the reactions of the other characters that Erko’s antics are beyond the pale, Jaana is a nice kid, Kreeta is clearly in the right and Topias is as silly as his son. The cast is game and a good time was clearly had by all. For the rest, I consider this kind of thing to be almost a tour of historical details, from the shape of the bread to the bridal headdress to the traditional dances to the construction of houses.

So, I give The Cobblers on the Heath my outsider, not-made-for-me stamp of approval. While the opening of the film is on the slow side, it quickly picks up the pace and turns into the kind of broad country farce that has been popular in films since the beginning. The cast is game, the film looks great and it can easily be considered one of director Erkki Karu’s best. Give it a shot.

Where can I see it?

Stream with optional English subtitles courtesy of Elonet. The film has no score but Finnish composer Uuno Klami wrote a song inspired by the play and a playlist made up of the song and other Klami works was quite suitable accompaniment for me.

Silents vs. Talkies

The Cobblers on the Heath 1923 vs The Cobblers on the Heath 1957

The Cobblers on the Heath was so nice, they made it thrice! The 1957 version was the third adaptation. (With the 1938 version as the filling in the sandwich and featuring two out of three Rinne brothers.) Countryside films were in vogue as feel-good fare cleaned up at the box office—another world war will do that—and director Valentin Vaala helmed a full-color version of Esko’s wedding trip.

Both films follow the play closely, though the 1957 production seems to be slightly more faithful. (More on that in a bit.) I won’t spend much time focusing on the plot as it is pretty much the same as the silent film. Instead, let’s focus on how the sound era cast and crew handle the characters and subject matter.

The biggest changes, in my opinion, are with the characters of Martta and Niko. While the 1923 film spends time establishing Martta’s plight as the only brains in a house of dingbats, the 1957 performance by Alice Lyly is harsher with more abusive treatment aimed at Jaana. Niko, on the other hand, had more opaque motives in the silent film while Holger Salin plays him as a knowing trickster trying to get back to his daughter as soon as possible.

Martti Kuningas takes the same approach to the character of Esko that Axel Slangus did and I presume this was the established method of portraying the goofy cobbler. However, the best role in the play is clearly that of the sly and conniving Mikko and Helge Herala clearly has a ball with the part.

I rather enjoyed the brawl scene between Esko, Teemu and his father. The timing is hilarious as Teemu is at home and about to receive his whipping when Esko barges in, father and son throw out the interloper, there’s a pause for a beat and then Teemu’s father drags him back inside for his punishment.

The 1957 version is far more faithful to the play’s five act structure. Rather than cutting between Esko, Iivari and Jaana, the film stays focused on one story at a time for long stretches. These long acts made sense onstage in interest of scenery changes but drag out the film. There is more editing between scenes as the action reaches its climax but not enough. Some rewriting would have worked wonders.

I also missed Karu’s constant use of fantasy, daydreams and flashbacks in the silent version of the film. The glimpse into the minds of the characters added a whimsical and playful quality to the story, while simultaneously giving it a more cinematic flavor. Vaala keeps things firmly in the present. I must say, though, that the color cinematography is nice, if not as sweeping as the moody tinted silent version, and the contrast between the muted green of the forest and the splashes of red on the costumes is most attractive.

I generally prefer Vaala to Karu but in this case, the 1923 version is the clear winner. While not quite as easy to follow as the 1957 film, the silent movie manages to create a rich and humorous world that is both visually appealing and fun. The 1957 picture is well-made but doesn’t have that special spark and it fails to take full advantage of its medium.

(If you want to see Vaala in top form with a himbo hero and a historical subject, I must recommend the delightful swashbuckler crossdressing rom-com Sysmäläinen.)

Where can I see it?

Stream courtesy of Elonet with optional English subtitles.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.