Acclaimed director Lois Weber focuses her attention on the embarrassingly low compensation for education professionals. She tells the story of the genteelly impoverished Griggs family and the various suitors seeking the hand of the daughter of the family, played by Claire Windsor.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD and Bluray.

A Chicken for Every Pot

Director Lois Weber was one of the top talents in silent era Hollywood and The Blot is one of her most famous and, for many years, few easily available films. Like many of her productions, it focused on a social issue and sought to win the audience over through a bit of drama and a bit of romance. In this case, Weber was concerned about the low pay of teachers and professors.

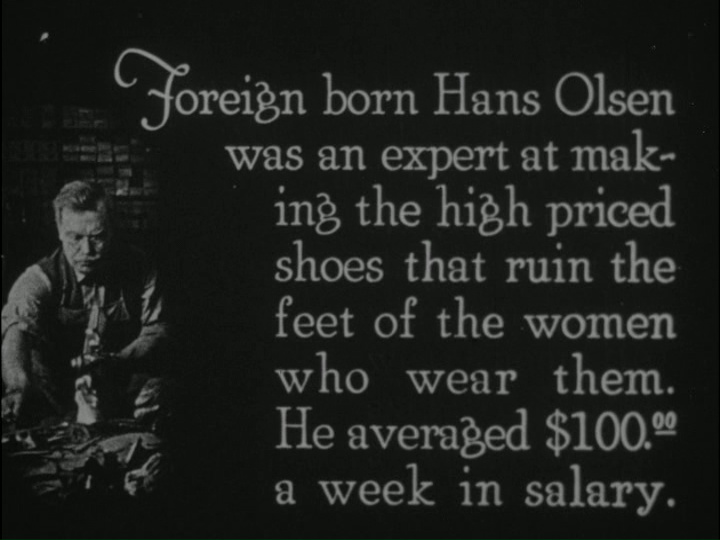

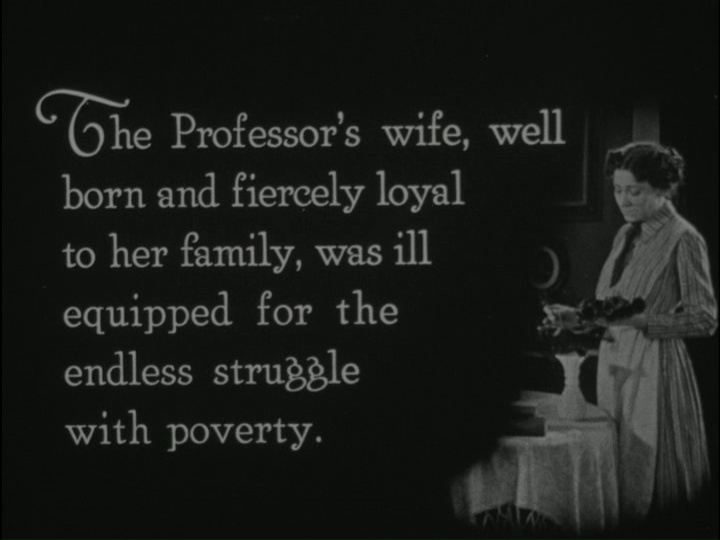

The story concerns the Griggs family and their wealthy neighbors, the Olsens. Professor Griggs (Philip Hubbard) is an underpaid educator trying his best to cram some education into the empty heads of his wealthy pupils. His wife (Margaret McWade) tries to make ends meet while engaging in a petty feud with Mrs. Olsen. Mr. Olsen pulls in a handsome salary of $100 a week as an expert shoemaker.

In contrast to the numerous children of the Olsens, the Griggs primly have one daughter, Amelia (Claire Windsor), who works at the local library. She has caught the eye of the eldest Olsen son, as well as the local minister and Phil West (Louis Calhern), one of Professor Griggs’ more unruly pupils.

When Amelia falls ill due to malnutrition, her mother is tempted to steal one of the two chickens Mrs. Olsen has displayed in her window to mock her poor but proud neighbors. She doesn’t go through with the theft and Phil sends over a chicken as a gift but Amelia believes it was stolen since she saw her mother sneaking around the Olsen’s back yard.

Of course, the real villain here is the suppressed wages of educators and the lack of a social safety net but I have to be honest, I kind of wanted Mrs. Olsen to fall into an open manhole when she tried to starve the Griggs’ cat, which had been dining in the trashcans.

Will Amelia recover her strength and marry Phil? Will the Griggs ever make a living wage? See The Blot to find out.

I saw The Blot fairly early in my silent film journey and it wrecked me. I don’t tend to cry at movies but this one hit me hard, particularly the climactic scene between Amelia and Mrs. Olsen. When I scheduled this film for review, I was curious to see if its emotional scenes would be as effective considering how many more silent movies I have seen since my initial viewing. Well, it still left me a sobbing mess, so mission accomplished there. The screenplay is a fairly blunt instrument—the chicken storyline sounds much more slapsticky than it is— but it is an effective one.

The screenplay by Lois Weber and Marion Orth places the women of the tale front and center. While the main male characters are introduced first and the love story is officially the main focus, much of the picture centers around Mrs. Griggs’ stress and despair as she realizes that she does not have the means to help her sick daughter or to even allow her to play hostess to her suitor. Margaret McWade’s performance is lovely and invites audience empathy but she is also not presented as an idealized saint, as is sometimes the case with silent movie mothers. She is proud and set in her ways, even when neither will do her or her family any good.

Not that the film is perfect. Claire Windsor lays things on a bit thick when she thinks her mother is a chicken thief and the belief that the idle rich can be converted to philanthropy just by meeting the right poors is naïve but overall, The Blot still packs a wallop. This is partially due to a talented cast and Lois Weber’s skillful direction and partially due to the fact that the issues raised in the film—the lack of financial respect for intellectual labor that cannot be easily monetized—are still very much a part of American culture.

Further, rather than heading into extreme melodrama, as many films dealing with poverty tended to do, Weber focuses on the slow, heartbreaking grind that is inevitable in such circumstances. No money to offer guests a snack, no money for shoes to be repaired or shined, no money for flowers to give to a sick friend, no money to feed pets, no money for reliable transport to avoid walking in the pouring rain, no money for essential nutrition. It’s far more tragic and heartbreaking than a cad and bounder with a big black mustache demanding rent from a proud beauty.

That’s not to say everything is as it was in 1921. One plot element of the film that illustrates the shift in the American economy is the price of chicken. These days, chicken is the cheap protein, often the cheapest that can be supermarket meat department. Obviously, the ethics of factory farming are high above my pay grade but suffice to say, prior to the mid-twentieth century’s advances in scientific poultry husbandry, chicken was considered a sumptuous special occasion food. Not completely out of reach to a middle-class family but hardly cheap. It was a food more likely to be served on Sundays or holidays than a casual weekday supper.

When a local political committee placed an ad in support of Herbert Hoover’s successful bid for the presidency in 1928, the proclamation of a chicken for every pot and a car in every backyard was seen as attractive but attainable lavishness. (Obviously, making such brags in 1928 was the height of bad timing and the statement “a chicken in every pot, two cars in every garage” was misattributed to Hoover himself, leaving him open to sarcastic attacks as he fruitlessly sought reelection at the height of the Great Depression.)

Mrs. Olsen’s double bird weekday supper in The Blot was purely conspicuous consumption and audiences of 1921 would have read the scene as such. A parallel that would work in modern America would be someone serving slabs of prime rib for a light dinner at home. Similarly, those $18 shoes that the youngest Olsen plays with would be about $250 in modern money. Again, not out of bounds as a saved-for luxury in a middle-class household but definitely not money that would be casually thrown around either. (In contrast, a “money saving bargain” pair of women’s shoes from Sears was priced at $3.48 or about $50.)

However, I do feel that one “blot” on this film is the decision to make the elder Olsens first generation immigrants. Sentiments like “foreigners taking the jobs, money, homes of real Americans while breeding like rabbits” have been a dark and dangerous thread running through American history and there is definitely a taste of that here. Also, I’m not sure that portraying designer shoemaking as somehow inferior said what Weber seemed to think it said.

Further, it was and is not uncommon for highly educated immigrants to discover that their book knowledge does them little financial good in their new home and being forced to obtain less lofty employment. This was sensitively portrayed in His People (1925), which featured Rudolph Schildkraut as an educated Jewish immigrant from the Russian Empire who must earn a living as a pushcart vendor in New York.

The Blot was released around the time when Hollywood decided that directing was a man’s job and Weber’s female contemporaries were being squeezed out of the mainstream industry. Weber herself was deemed preachy and out of step with modern taste. She directed two films in 1927, went on hiatus and then made her last picture as director in 1934. She faded into obscurity for decades before historians rediscovered her some four decades later. With her reemergence, charges of preachiness appeared as well.

In the end, “preachy” attached itself to Weber so firmly that it is still one of the more common ways to describe her pictures. While she certainly did approach her work as a moral duty, she was not so very different from her 1910s-era male contemporaries and was certainly more subtle about it than, say, D.W. Griffith. You can see direct parallels to Weber’s tone in the 1910s work of Raoul Walsh (e.g. Regeneration) and Maurice Tourneur (e.g. Alias Jimmy Valentine), for example. However, “preachy” somehow has not attached itself to either man.

While Weber’s decline in popularity is often associated with Hollywood’s general move away from progressive politics post-WWI, the role of gender cannot be ignored. In the book Lois Weber in Early Hollywood, Shelley Stamp points out that Weber’s feminine perspective, once seen as her greatest asset in tackling sensitive topics, was linked by contemporary critics to the flaws of her productions. Further, the general purge of women from the director’s chair cannot all be put down to “preachy” material.

This is further illustrated by the fact that, since her rediscovery, discussions of Weber’s body of work have often been marred by bald sexism. In one case, a historian suggested that Weber’s decline was due to her divorce and used this as evidence that she needed her husband’s “strong masculine presence” to carry on working. Ugh.

Weber had a very definite mission and message that she wanted to put forward in The Blot. While the ending lacks true resolution—mainly due to its being framed as a call to action—and the lessons are quite direct, it still packs an emotional wallop.

The bottom line is that The Blot still works a century after it was released. It’s one of Weber’s more accessible films and has remained a favorite for a reason. Between The Blot and Suspense, newcomers to her body of work will enjoy an excellent cross-section of her talent.

Where can I see it?

Released on DVD and Bluray as part of the Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology box set.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Dear Silent Film;

A while ago I read your fantastic review of Michael Strogoff and just plowed into research trying to find the 3 hr silent version unsuccessfully. However I just bought a near 170 minute version from Raremoviesandall.com which I can’t wait to receive and view. FINALLY! Just thought I’d tell you this in case you weren’t aware of this release. I just hope it is of good quality. Thank you for your fabulous work on your column. I always look forward to reading it and finding gems just like Strogoff. Thank you. George.

Thanks! I believe that version is derived from a VHS tape copy. I am really hoping for an official HD release at some point. We have just seven months until 1926 is out of copyright jail, so…

Who is preachy, if Griffith isn’t? That his preaching varies between nuts and naive shouldn’t be used in his favor compared to Weber who discusses something that is a real issue even today.

Academic poverty is common especially in humanistic sciences that aren’t so straightforwardly profitable, but professors are the well paid exception. The closest parallel between The Blot and today are perhaps kindergarten teachers who at least here need a university degree, but who earn less than many typical manual workers.

Yes, the biggest academic pay story here in the US is the fact that schoolteachers take on second jobs at three times the rate of other workers, often doing this in order to afford classroom supplies. The budget for and reimbursement of such expenses is really low in most school districts.