Pushkin’s tale of a jilted peasant and an unfaithful prince as adapted for the screen by Russian film pioneer Vasily Goncharov. A rare example of pre-Revolution Russian folklore on film with a dash of French fantasy.

Home Media Availability: Released on DVD.

Does this look like Hans Christian Andersen to you?

Water maidens of various types are a staple in world folklore and there are countless variations in European mythology alone and Europe is where we are focused today. A rusalka is a Slavic water nymph, helpful, mischievous or murderous depending on the time and place, and Alexander Pushkin’s verse play, Rusalka, drew from the belief that rusalki were women who had died tragically and sought revenge by tangling fishing nets and tickling men to death. It’s a living. (Rusalki even had their own week-long holiday.)

Vasily Goncharov was one of the first filmmakers in Russia, period. Russia had been importing films from France, the United States and Denmark, but there was a demand for purely Russian material made by Russian talent. Given Pushkin’s continued wild popularity (his reputation can be compared to Shakespeare) and the fact that his unfinished 1832 lyric drama Rusalka had been adapted for the opera stage by Alexander Dargomyzhsky, it made sense to follow suit and adapt this work to the screen.

It’s important to remember that when this film was made, screen adaptations often were kind of the Cliff’s Notes version of popular works; all the best parts but not necessarily the linking scenes and underlying structure. The audience was expected to be familiar with the story already and were given minimal assistance in following along.

Now, I am writing for an English-speaking audience eleven decades after Rusalka was released, so I think it’s fair to give you a quick synopsis of Pushkin’s Rusalka as I do not think the film makes much sense without its context:

The play opens with a miller scolding his only daughter for giving herself to her lover, a prince, when she should have played hard-to-get and forced him to propose to her. The daughter insists that her prince will return, he has just been busy. The prince does indeed return but gives her an “it’s not you, it’s me” speech, tosses some money at her and leaves her for his fiancée, a princess. The distraught and pregnant daughter drowns herself.

At his wedding, the prince keeps hearing a song of condemnation and feels sure that his jilted lover has returned for revenge but he cannot see her. However, he is constantly drawn back to the now-abandoned mill on the Dnieper River. The miller has gone mad and claims that he is a raven and is cared for by his granddaughter, who lives with her mother at the bottom of the river.

The miller was right. His daughter has become a rusalka and wants revenge. She knows that her lover has returned and sets a trap. She sends her child, his daughter, to the surface to lure him into the water and—

The play ends here. Pushkin was killed in a duel before he finished it.

(If you would like to read an English translation of the play, one is included in the collection The Bronze Horseman: Selected Poems of Alexander Pushkin.)

Dargomyzhsky’s opera closely followed Pushkin’s text and, of course, could not end on a cliffhanger, so a finale was crafted on:

The prince is lured into the water as his wife tries to stop him. Before she can reach him, the miller pushes him into the water and he drowns. The rusalki carry his body to their queen.

Call me an old softy but multiple generations of a family coming together for a group project just gets me in the old feels, you know? This is what I call family entertainment.

What’s that?

I have been informed that I cannot describe a story that ends with a corpse tableau as “family entertainment.” You’re no fun at all.

(On a side note, Vladimir Retsepter claimed to have discovered that Pushkin had revised and finished Rusalka before his death. The completed version does not exist but the discovery was made by studying the corrections made in pencil and ink on the manuscript. Retsepter presented his findings in the 1970s, which were published in a bilingual Russian-English edition as The Return of Pushkin’s Rusalka. Debating the veracity of this discovery is well beyond my pay grade but since it transpired six decades after Rusalka was filmed, it doesn’t really change the nature of the adaptation as Goncharov would have only had the unfinished Pushkin text and the Dargomyzhsky opera to work from.)

Anyway, Goncharov follows the Pushkin-Dargomyzhsky story closely, for the most part. The miller’s daughter (Aleksandra Goncharova) is spurned and paid off by the prince (Andrey Gromov) and collapses when he leaves her. Her father, the miller (Vasily Stepanov), rushes to his distraught daughter but she throws herself into the Dnieper River.

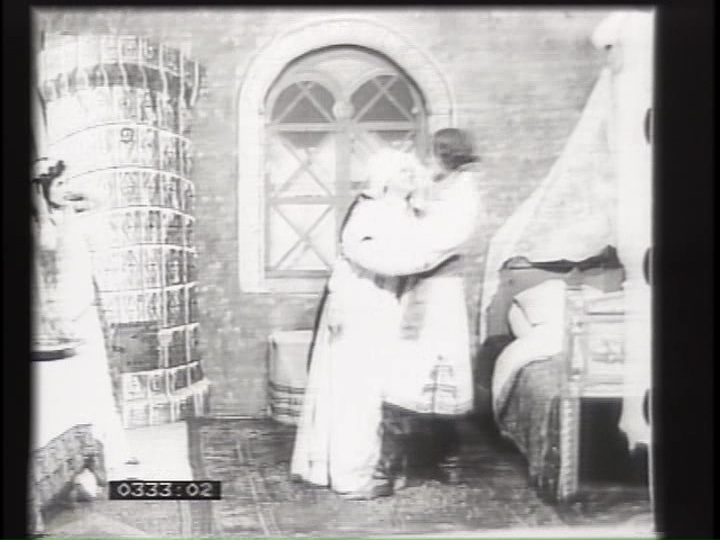

The film does make some changes from the play and opera in order to take advantage of motion picture special effects. Instead of a mysterious voice condemning the faithless prince, an apparition of the miller’s daughter appears in the middle of the wedding banquet, visible only to her betrayer, and then disappears again courtesy of a stop trick.

When the bride and groom retire to the marital bed chamber, the miller’s daughter appears again, causing the prince to abandon his unfortunate bride and pursue the apparition back out to the banquet hall. She appears and disappears once more, which rather puts a damper on the festivities.

(Incidentally, the bride and groom are being showered with hops, a traditional part of a wedding.)

Eight years pass, the prince no longer cares for his bride but is instead drawn to the banks of the Dnieper by a mysterious force. (Spoiler: It’s the rusalki.) The prince runs into the mad miller and is then lured to the water by the miller’s daughter and his own child. He leaves his hat and coat on the bank and slips into the water. When the princess goes in search of her husband, she only finds his abandoned clothing.

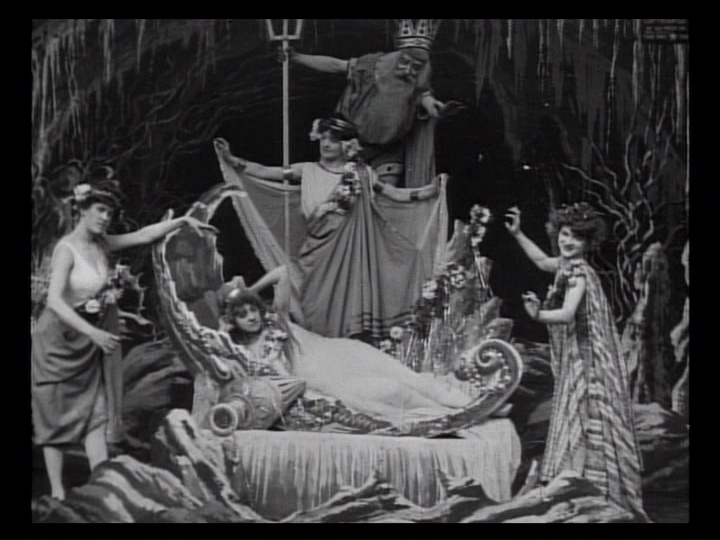

At the bottom of the Dnieper, the miller’s daughter kisses the prince’s dead body and her rusalki sisters dance around in triumph. Well done, ladies!

By the way, in case you were curious, the Czech opera Rusalka by Antonín Dvořák bears very little similarity to this tale of vengeance and ends with something of a reconciliation between the lovers. All in all, Dvořák’s Rusalka has much more in common with Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid than anything Pushkin wrote. I far prefer the Pushkin narrative, myself. Good opera, though.

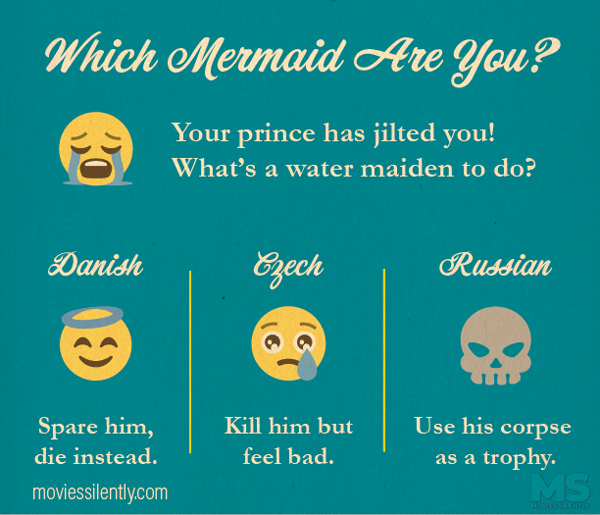

In case you need a quick reference guide, here are the basic differences between Danish, Czech and Russian water maidens:

Now, the most obvious thing to modern viewers is how much the final tableau of the film was influenced by French films and likely the works of Georges Méliès. Ending films with a spectacular tableau was something of a signature for him and considering the wide popularity French films enjoyed in Russia, it is quite reasonable to suppose that the works of Méliès or a director working in a similar style (Segundo de Chomón, for example) influenced Goncharov.

I have read that Rusalka was allegedly influenced by the 1904 Méliès film The Mermaid but other than a similarity in title, there really isn’t much evidence of that. The Mermaid was a playful, cheeky showcase of an illusionist’s bag of tricks with plenty of meta humor. It ends with a tableau but, as we have discussed, so did a great number of Méliès films. Méliès loved aquatic themes and only a fraction of his work survives. It’s possible that Goncharov was directly referencing a single, possibly lost, film but it is also likely that he was riffing on the general French fantasy style.

However, we must also remember that French films were influenced by the grand stage production of the time and that Rusalka was a Russian opera. That means that the ending tableau may have been based on the production design and costuming of a contemporary performance of that opera.

Goncharov is sometimes written off as a primitive filmmaker, which is not entirely fair. His work was on par with other filmmakers of the era, not the most advanced but Rusalka has some interesting flourishes. There is a subtle pan in the opening scene in order to capture all the action and a more dramatic one used during the riverbank scenes. The apparition scenes are handled well and are suitable creepy. And, of course, the final underwater rejoicing over the prince’s corpse are wonderfully eerie.

The production is not merely a filmed play but the creative team made an effort to adapt the story for the cinema. While some of the behavior of the characters may seem odd if you are unfamiliar with the source material (the miller flapping his arms like a bird, for example), this film was made for a specific audience at a specific time and we cannot hold its “best scenes” format against it. It’s up to use to perform a bit of research to reveal this picture’s quality.

The performances are a bit on the operatic side but this would have been expected considering the dramatic nature of the story. There are some effective moments as well, including the sorrow of the prince’s wife and the gleeful performance of the child playing his ruskalka daughter.

All in all, this is a fascinating work of early Russian cinema and will be of particular interest to anyone who enjoys seeing folklore translated to the screen.

So, let that be a lesson to you. You may be safe toying with the affections of Danish or Czech mermaids but anger a Russian mermaid at your peril. Let’s just say that there’s a very good reason why Disney has not opted to adapt this particular bit of folklore.

Where can I see it?

Was released on DVD as part of Milestone’s now out-of-print Early Russian Cinema set with a piano score by Neil Brand. The edition is dated 1992 and I would love to see a new edition of this set released in HD format, the better to appreciate the details of these foundational works of Russian film.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.