Welcome back to Silent Movies 101, where we examine aspects of the silent era in a beginner-friendly format. You can catch up on past posts here.

To many people, black and white is synonymous with “old” movies. Therefore, it comes as a surprise when they discover just how colorful the world of silent film was. We are going to be going through a light introduction to these various color processes. Obviously, technical jargon will be kept to a minimum and the gorgeous images will be allowed to speak for themselves.

To established fans: We will be skipping over lesser-known color techniques and cannot dive too deeply into the history of each method. Remember, this is a light and fun introduction for newcomers. I promise to let you show off after class but this isn’t the time or place.

Broadly speaking, silent film color can be divided into three categories:

Tinting and Toning

Hand painting and Stencil Color

Early Color Film

We are going to take one category at a time.

Tinting and Toning

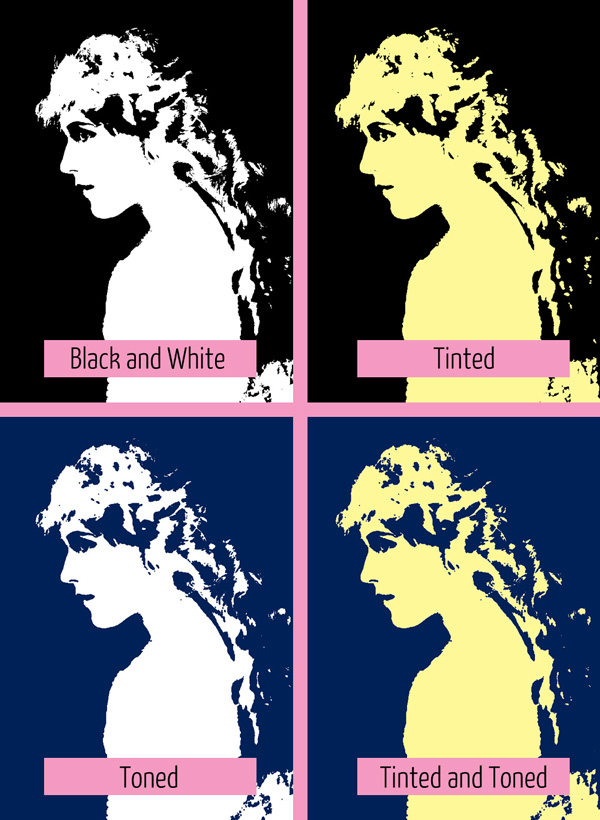

By far the most common method for adding color to silent cinema was to use tinting and toning. That is, the entire scene would be colored a particular shade. What’s the difference between tinting and toning? To put it simply, tinting colors the “whites” while toning colors the “blacks” of the film. Some films were tinted in one shade and toned in another for a beautiful two-color effect.

Here is a simplified chart showing the difference:

And here is an example of actual film that was tinted and toned. In this case, pink tint with dark blue toning.

For practical purposes, tinting and toning are often generally referred to as tinting. In his valuable (but highly technical) book Silent Cinema: An Introduction, Paolo Cherchi Usai writes that about 85% of silent films featured at least some color tinting and toning. Tinted footage could be achieved by either using a chemical process after the scene was shot or by using pre-dyed film stock.

Tinting silent films could either be literal (blue for night, gold for candlelight, red for flames, etc.) or more abstract (green or lavender for eeriness, pink and blue for magic, as we saw in the Snow White screen cap above). For an example of more literal coloring, in Hell’s Hinges, tints are used to great dramatic effect as the hero begins shooting down kerosene lanterns and finally manages to set the entire town ablaze. Sepia turns to wine red as the fire erupts.

In The Sea Hawk, daytime scenes are either tinted amber (more literal) or rose (more abstract).

In Sparrows, the grim horror of the swamp setting is heightened by sickly lavender tints:

Controversy: In some cases, only black and white copies of a film survive. The tints will sometimes be restored for re-release, using original production notes to make sure the correct colors are employed. However, if such notes do not exist restorers have to make educated guesses. Is it better to keep things black and white or guess at the original filmmaker’s intentions?

Recommended films with tinting and toning:

The Dragon Painter (1919): This beautiful Japanese-themed romance features subtle and tasteful tints and tones that perfectly capture the artistic mood of the film. Shades of amber, aqua, blue and gold create a lovely and natural world that seamlessly blends with the bittersweet love story.

The Burning Crucible (1923): This strangely wonderful and wonderfully strange genre mashup also boasts of some gorgeous and unique color combinations that go well beyond the abstract. Yellow tint with green tone (pictured above), neon red, rose, amber, deepest blue… it’s all here and it’s all gorgeous. Plus, the movie is wild blend of mystery/comedy/drama with some mad innovations. Good stuff.

Hand-painting and Stencil Color

These color methods are exactly what they sound like. The physical film cell has color applied to it directly, either freehand or using stencils. Color is only limited to the imagination.

Vocabulary: As stencil color was applied by hand, it is sometimes referred to as hand-colored stencils. For the purpose of clarity, I will use hand-coloring only to refer to freehand application.

On occasion, I do get people asking me about stencil color. Is it legit? Is it historically correct? I don’t blame anyone for being suspicious. Modern colorization of films with black and white cinematography is a desecration, a pathetic attempt to expand the film’s appeal to an apathetic audience while alienating its core fans.

Hand-color and stencil color is not like that at all. Often found in French films (but by no means exclusive to them), it was a creative expression, a way of beautifying film. It was part of the plan for the movie, an extension of the filmmaker’s vision. And guess what? In France, women were quite often the brains of the color outfit. (This was due to a common gender stereotype that women were innately suited to the task but unlike many of these stereotypes, the result was higher wages and better positions.)

Early hand-painted and stencil-colored films have a homemade, blotchy quality, which is charming in and of itself. Later stencil processes were considerably more detailed and fit the action almost seamlessly. The process gives films a glorious watercolor look and it is a pleasure to view them.

Because the process was so painstaking and time consuming, most feature films would employ hand or stencil color for only the most important scenes. However, there were some features that were 100% color.

Vocabulary: When a movie uses color for only particular scenes, it is usually described as having color sequences.

An example of using hand-coloring for a dramatic scene can be found in the restoration of Battleship Potemkin. The restoration team used freehand painting to brighten the red flag of the uprising, just as it had been colored on its initial release. (There is some squabbling as to exactly how many times the red flag was shown but there is no argument that it was indeed painted that color.)

Joan the Woman effectively used the Handschiegl color process (similar to stencils) for the flames during its tragic and inevitable climax.

Remember: Some viewers see a stencil or hand-colored silent film and assume that it is a more modern (and deservedly maligned) colorization process. It isn’t. When a silent film does have reproduced stencil or hand color, it is almost always based on the original colors of the release and backed by actual film fragments, contemporary descriptions and other historical evidence.

Recommended films with stencil color and hand painting:

A Trip to the Moon (1902): Thought lost for decades, the elaborately colored version of Georges Melies’ masterpiece was rediscovered in a Spanish archive and restored. Elisabeth Thuillier had her all-female team of painters carefully add colors to the film, one frame at a time, one print at a time. Each painter was responsible for a single color. The result looks practically edible.

Cyrano de Bergerac (1925): This epic adaptation of the famous play features stencil color in every single scene, a process that took three years to complete. In his essay on the picture’s production, film producer David Shepard describes the stencil color process: “In Paris, the film was projected frame by frame onto a ground glass screen, where Mme. Thullier, the most famous stencil-color artist, selected the colors and traced, one color at a time with a device called a Pantograph, the area of each frame of film chosen for each of up to four colors.”

Oh and the movie itself is really good too. See it. (The rest of the essay is available for download in PDF format here.)

Early Color Film

The two methods discussed so far were both about adding color to a film. Motion picture film that captured natural color had been experimented with for years (and the history of these experiments would be a book in itself) but the most commercially viable process was an early form of Technicolor.

(A quick reminder that this is a highly simplified guide and we will not be touching the heavy tech stuff.)

The color film used in silent films is often referred to as two-color. This is because two-color Technicolor only captured red and green. As a result, films made using this process did not have a full palette.

However, the colors used in two-color films are often more subtle than the obnoxious, eyeball-searing shades often employed in “true” color films of the sound era. Two-color Technicolor has a subtlety and beauty that is often ignored in the stampede to complain about something that is missing.

Because color film was expensive and difficult to deal with, it was most often used in relatively short sequences, usually during scenes that the producers considered to be show-stoppers. However, some silent films were shot entirely in color. (It’s quite humorous that the 1939 version of The Wizard of Oz is praised for its “innovative” sepia-to-color when the concept was decades old.)

The 1929 film Redskin (by the way, the title was intentionally provocative and the term is treated as a slur throughout the picture) uses color to capture the beauty of traditional Navajo and Pueblo costumes and art. It used color for the Native American scenes and sepia tints for everything else. (Take that, Oz!) The color is stunning:

Recommended movies shot on early color film:

The Black Pirate (1926): Swashbuckling superstar Douglas Fairbanks liked to use the best of everything in his productions and he could afford it. In this case, he shot his pirate adventure entirely in the expensive and finicky new color film. The palette is subtle and resembles an N.C Wyeth illustration, which was Fairbanks’ goal. The film is a fun adventure and the light touch with color pays off richly.

Ben-Hur (1925): This silent epic uses color sequences in a more traditional manner. Color is reserved for more religious sequences and during a victory parade with the rest of the film tinted. It is fascinating to see which scenes were deemed worthy of color.

This is just a small sample of the colorful world of silent film. It was an era of visual beauty that is still unmatched in motion picture history and this was thanks to the hard work of the men and women who created color on celluloid.

Great stuff as always, Fritzi. No matter how much a person thinks they know, there’s always more to learn, and these beginner classes are just fantastic. I almost feel like I should be paying tuition.

Thanks so much, glad you are enjoying!

Nice article—very informative! I can appreciate the hand coloring and the early technicolor, but I have to admit that I’ve never particularly cared for tinting in silent films. I know it was an important part of the creative process, but for some reason, I find it distracting and would just prefer to see it in black and white.

I know some people feel that way. I am a huge fan of tinting and actually find films to be naked without it. (And, of course, there are times when the narrative will not make sense without the tinting. Day-for-night shots tinted blue, for example.)

People are always shocked when I tell them color film was not invented in the 1950s. Thank you so much for such an easy to digest article on the subject!

Thank you! Yes, obviously color was invented in 1939 for The Wizard of Oz 😉