Mabel Normand is imperiled by Ford Sterling yet again and it’s up to Mack Sennett to save the day with a little help from famous racecar driver Barney Oldfield. This zany comedy makes use of a very old cliché… and that’s where things get sticky. Time for some myth-busting.

This post is part of CMBA’s Planes, Trains and Automobiles Blogathon. Be sure to read the other great posts!

Aren’t silent movies the ones that have the heroine tied to the train tracks?

It’s safe to say that when the general public thinks of silent films, they think of a very specific situation. Bizarrely specific, in fact. A screaming heroine is dragged to the railway by a cackling, black-clad villain (complete with top hat and waxed mustache) and then tied to the tracks while the handsome hero races to the rescue. Naturally, the print is scratchy and jittery and ragtime piano music is being pounded out to heighten the mood.

The problem is that this film never existed.

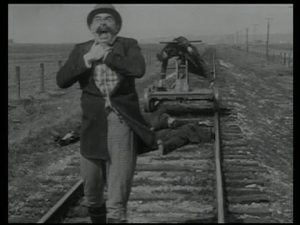

When arguing this point, people determined to believe that their pre-conceived notion of silent films is correct will trot out this still of the allegedly “iconic” scene:

Checkmate, silent movie fan!

Um, not really. You see, that’s a comedy. Specifically an incredibly broad comedy spoofing the pop culture of yesteryear. It would be like dragging out a modern spoof of Saturday Night Fever’s dance scenes and using it to prove that disco was the top musical genre of the 2010s.

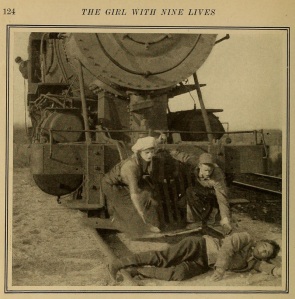

But where is that still from? Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life, a 1913 short from Mack Sennett’s mad band of comedians. The heroine is Mabel Normand, her lover is played by Sennett himself and the villain is Ford Sterling, the resident comical baddie of the studio.

In his book The Bad Guys, film historian William K. Everson wrote that when Sterling wanted to be bad, he took the audience into his confidence. “When villainy was on his mind, the audience knew it: in close-up he’d “tell” the audience just what he was going to do. No matter that there was no sound, and that the briefest subtitle might condense what was saying, he told the audience his plans in detail, scowled, smacked his lips in glee, looked furtively around to make sure that only the audience had heard him, lent emphasis by pounding his fist, and then hopped off to put his plan into operation.”

Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life is very much along these lines. Mabel Normand and Mack Sennett play a pair of lovers and Sterling is the jealous rival. Enraged that Normand will not accept his romantic overtures, he kidnaps her and, with the help of some cronies, chains her to the tracks, pounding in stakes with a comically oversized mallet.

Sennett realizes that Normand is in danger but the train is already on the way. Fortunately, real life racecar driver Barney Oldfield is in town and he has his car with him. Sennett leaps in and they drive together to try to save Normand. Sterling, meanwhile, has commandeered the train so he can have the pleasure of squishing Normand personally. He’s no match for Oldfield’s car and the heroine is saved. Sterling is so enraged that he strangles his cronies, shoots the Keystone Cops and, finding himself alone, strangles himself with his bare hands. Wait, what?

It’s easy to see why Sennett and Co. dusted off the hoary old cliché. Barney Oldfield had broken a world record just three years before, driving his car at the then unheard-of speed of 130 miles per hour. He was dubbed the Speed King, Master Driver and the Fastest Man in the World. Having their celebrated guest outrun a locomotive would create an ideal comedic situation that would also showcase his skills as a driver. It was a win-win.

The thing is, this film no more proves that the trope was common in serious silent films than Snidely Whiplash’s antics in The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle prove that films of the 1960s regularly featured women tied to tracks by men in top hats. Spoofing yesterday’s pop culture is not a modern invention. Silent movie people were more than happy to poke a bit of fun at the clichés that had thrilled granny. Considering the dramatic shift in culture that was occurring when this film was made (heavier-than-air flight was a mere decade old, the automobile was starting to replace the horse, the world was on the eve of the Great War) it’s no surprise that silent films reacted to their baffling and exciting times with laughter at the naïve past.

So, what were serious silent movies doing at this time to create suspense? Let’s see… During this time period (circa 1908 to 1913), the payroll robbery, the home invasion and the murder/attempted murder to gain an inheritance were all pretty popular. However, we must remember that the suspense film was not the only genre being made. Audiences liked a variety and so psychological dramas, muckraking social films, zany comedies, sweet romances and dark tragedies were all popular. So when we talk about silent suspense/adventure films of this period, we are talking about a fraction of a fraction of total silent film output.

Those zany comedies made fun of new and old pop culture, spoofing everything in sight. And yet even in these wacky films, the tied-to-the-tracks cliché is incredibly rare. (It’s worth noting that the earliest examples of people being tied to tracks and sawmills on the Victorian/Gilded Age stage involved men as the victims and women as the rescuers. So when people “subvert” the trope by reversing the genders, they are actually just returning the cliché to its roots.)

The usefulness of this cliché on the stage is obvious. It was a way for audiences to be held in great suspense and it all could be done with a train whistle and some lights to represent the oncoming locomotive. Noted silent film cinematographer Karl Brown wrote enthusiastically about enjoying such cheap traveling stage productions as a boy and particularly that suspenseful light that spelled the victim’s certain doom before the hero arrived to save the day. But notice I said “stage productions” and Brown was born in 1896. By the mid-teens, the traveling stage melodramas had been almost completely replaced by the movies and motion picture audiences demanded variety for their nickel. Many members of the silent film community got their start in these traveling stage productions and were likely eager to spoof the old cornballs.

(Actually, he was trying to escape the villains and fell onto the tracks. I’m not sure if that makes it better.)

I have seen hundreds and hundreds of silent films in my day and I can tell you that I have never, not once, seen this scenario play out in a serious drama. Yes, people sometimes do nearly get run over by trains but they also are endangered by automobiles, airplanes, ships, streetcars, dogsleds, motorboats, bicycles, inflatable fish and just about any other form of transportation you can name. Trains were popular, especially in early silent film, because cars were only just starting to be commonplace and the railway was still the most common way to get from Point A to Point B for the average American moviegoer.

Let’s bring William K. Everson back into the conversation. One of the earliest and most enthusiastic defenders of silent film in the post-silent world (he was born in 1929) Everson’s tart and opinionated writing style is quite refreshing. While I don’t always agree with his findings (and that’s okay) I admire his expertise. His massive knowledge came from watching hundreds, thousands of silent films, some of which have now been lost to the ravages of time.

Here’s what he has to say about this so-called iconic trope:

“Ford Sterling, Wallace Beery, Edgar Kennedy, and other Sennett heavies drew strongly on the old Victorian melodramas, with such situations as tying the heroine to the railroad tracks. Actually, although this is often considered one of the stock melodramatic situations of early movies, I have never seen it done except as a burlesque of earlier traditions of melodrama. Heroines may have fallen unconscious on the tracks, or had their feet jammed between the rails by accident (editor’s note: men had this happen to them as well) but being strapped to the tracks by the villain was purely and simply a comic device, and the byplay made sure that the audience knew it.”

You’d think this would be enough to kill the myth. After all, Everson published The Bad Guys all the way back in 1964. Over half a century later, the myth is as common as ever. The problem is that people move the goalpost when arguing this point. At first it’s all “Yes, silent movies always had women tied to railroad tracks by villains with mustaches and top hats.” Then when they see that no serious examples are forthcoming, they shift ground and either try to claim comedies or twist any danger from a train into supporting their argument. The thing is, this myth is incredibly and strangely specific. Mustache. Top hat. Villain. Woman. Tied to the train tracks. Serious danger. And it simply does not exist in mainstream drama.

Like so many myths about silent film, this one has bizarrely stubborn supporters. I remain baffled as to why people become so invested in a narrative even after is has been thoroughly disproved. They feel that there must be a serious example of this cliché somewhere and they grasp at the flimsiest straws to prove their point. The thing is, even if there is such a film, it still doesn’t change the fact that there are literally thousands of silent films that contain no such thing. Iconic? Hardly. (Remember, their claim is that this trope was so common that it actually symbolized the silent era.)

The real iconic symbol of silent film? For early film, I think the rocket in the eye of the moon from A Trip to the Moon has the strongest claim. For silent features, I’m going to have to go with Harold Lloyd holding onto that clock face for dear life in Safety Last. For second place, that famous still of Rudolph Valentino and Vilma Banky canoodling in The Son of the Sheik.

Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life was a pretty typical Keystone offering. Mack Sennett mugs himself silly but Mabel Normand and Ford Sterling are as fun as ever. It’s a solid C+ for the studio, time and place but is mainly notable today as one of those “tied to the railroad tracks” films. Of course, though, anyone who would suggest this film was typical for silent dramas of the period or that the cliché was played straight has no place in film criticism.

Movies Silently’s Score: ★★½

Where can I see it?

Barney Oldfield’s Race for a Life was released on DVD as part of the Slapstick Encyclopedia.

Some things just refuse to fade away. This isn’t always a bad thing. I’m not a race car fan, but even I was familiar with the name of Barney Oldfield.

Yes, Barney Oldfield is a good thing to remember. Insisting that a comedic scene is dramatic on the other hand… 😉

Great myth busting, Fritzi! A lot of points you made illustrate how unfairly our society views early filmmakers. Instead of being widely celebrated for their cleverness and innovation, they’re often derided for being boring, etc. Fabulous post.

Yes and especially by people who have never seen their work.

I have to ask: What movie involves people endangered by inflatable fish?

The Mystery of the Leaping Fish appropriately enough. 😉

TV shows – Isn’t that where people are stranded on an island, and can invent everything but a way home? Books – aren’t those the things that schools give out to help put students to sleep? Music – isn’t that the noise that young folks listen to? etc. More seriously, Conformation Bias is why people believe things despite strong evidence to the contrary.

Ha! All TV show are Gilligan. 😉

I second Catan Woman’s statement. I think I knew the name Barney Oldfield from birth! Great post. Very entertaining.

Thank you!

Great post and highly informative! Anyone who searches for women tied to train tracks should be lead to this post automatically. The only experience I had with the trope was through Dudley Do-Right…so we can blame Nell and the Mounties since that is all that is in Canada isn’t it? 😉

Everyone knows that Canada is rife with green skinned villains 😉

Fantastic post! I loved the images of the train track situation from the 19th century stage to movies! I had no idea it was such a trope in Victorian theater. This line was perfect: “It would be like dragging out a modern spoof of Saturday Night Fever’s dance scenes and using it to prove that disco was the top musical genre of the 2010s.” Thank you for an entertaining and illuminating post!

Thank you so much! Yes, the roots of this trope are endlessly fascinating.