The oft-filmed tale of an Englishman who is branded a coward and spends the rest of the film proving that he most assuredly is not. This version (released at the height of the sound transition) was one of the very last silent movie hits. It also features William Powell and Fay Wray before they hit the big time and it is directed by a couple of guys mostly known for making a film about a really big ape…

I’m also covering the famous 1939 talkie remake. Click here to skip to the talkie.

What is bravery?

By 1929, it was clear that sound movies were not a passing fad. Talkies consistently scored at the box office while silent films that would have been enormous hits in previous years struggled to break even. Talking sequences were hastily filmed and slapped onto existing silent productions. The silent film, with a few rare and notable exceptions, would be dead in America by the end of the year.

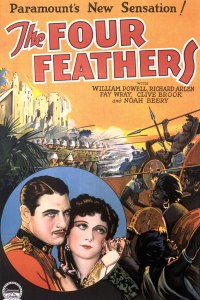

And yet the art still had a few hits left in it and The Four Feathers was one of them. Based on the 1902 A.E.W. Mason novel of the same name, it featured lavish location photography of the people, landscape and wildlife of Africa. The film was augmented by synchronized music and sound effects and boasted the finest cast Paramount had to offer at the time.

However, if it had simply been a beautiful late silent with some interesting location shots, it likely would have been forgotten like so many other silent movies released during the transition to sound. This is where a large ape comes into the picture.

The Four Feathers was directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack. It featured Fay Wray as the leading lady. The trio would make history a few years later with King Kong but their careers had already taken off. Fay Wray had been a von Stroheim leading lady. Cooper and Schoedsack had made names for themselves as directors of nature documentaries and this led to their being offered work in fictional film.

But before we get further into a discussion of Cooper, Schoedsack and the third director, Lothar Mendes, let’s take a step back and talk about the story they were telling.

The original novel The Four Feathers told the tale of a young man named Harry Feversham who is so terrified of being a coward that he quits the army on the eve of a campaign. (You can read a free public domain version here.) His three best friends and his hyper-patriotic fiancée then fulfill his worst fear and hand him white feathers to show that they hold him in contempt. This gesture inspires Harry to follow his friends to their battles in Sudan, display his bravery and force them to take back their feathers.

The novel is a plodding affair. I have a pretty high plod tolerance but I had to give up after a while. While the action is happening in Sudan, much of the story is spent in English gardens and around tea tables, discussing the events in a veddy veddy proper manner. Of course, such a tale would never do in a visual medium like the silent.

When we first meet our main characters, they are still children. Harry is determined to marry Ethne (in the non-binding kid playtime sense) but she will not hear of it unless he dresses up as a soldier. Later, Harry’s father entertains him with tales from the Crimean War. There is much talk of bravery but the tale the sticks in the sensitive young man’s mind is the story of a soldier whose nerve broke. Harry’s father boasts that he did the only proper thing: He sent the coward a white feather and the soldier was goaded into suicide. Very properly too.

Harry grows up to be Richard Arlen (hubbah!) and he dutifully joins the army and becomes engaged to Ethne (Fay Wray). However, he lives in terror that his nerve will fail him in combat and the coward’s fate will be his.

Harry’s three best friends are Durrance (Clive Brook), Trench (William Powell—told you the cast was good) and Castleton (Theodore von Eltz). They are together the evening that Harry receives a fateful telegram. The quartet’s regiment is being sent to Sudan (spelled Soudan). Harry hides the telegram and announces that he is putting in his resignation.

Harry had tossed the telegram into the fireplace but he forgot to check and see if the fire was burning. Whoopsy. Trench discovers the incriminating paper. You just know that they are going to do something about this.

Harry is with Ethne when he received a box containing three white feathers. He acknowledges to Ethne that they mean exactly what they have always meant. (Pillow fight! No?) Ethne is understandably annoyed that he would try to marry her under false pretenses. She hands him a white feather of her own.

News spreads to Harry’s father, who is very ill. His final words are to instruct his son to shoot himself. Ouch.

His father’s death inspires Harry to take a new path. He intends to track down his friends and force them to take back their feathers. Easier said than done, though. Travelling to Sudan as a civilian, Harry waits for an opportunity to display his mettle.

Fortunately, the British army in this film is remarkably incompetent. Durrance and Trench are holding a fort in enemy territory but Durrance is wounded during an attack and Trench is captured while trying to deliver a message. This looks like a job for…

Richard Arlen gets no respect. I mean none. Written off as a pretty face. Of course, it doesn’t help that the two movies from his silent career that get the most play also contain his dullest performances (Wings and Beggars of Life). He is also not helped by the hatchet job performed by Louise Brooks, which gets merrily repeated without anyone bothering to track down his other performances.

Just for the record, I have no idea why people think former actors/directors/writers bashing Hollywood and their co-workers and exes for pages on end is interesting. I don’t like to listen to people whining about their jobs, bosses, co-workers and exes in real life. Why would I read an entire book about same? If you hate your job so much, the door is that way. Don’t let it hit your rear. Also, it is silly since the whole reason anyone is reading this person’s book is because of their horrible, awful, dreadful, torturous Hollywood career. It’s like when non-musical celebrities use their fame to release an album and then throw a tantrum when someone brings up their other career. (Why yes, this does remind me of a Mitchell and Webb sketch, what of it?)

I’m not saying that celebrities memoirs have to be sweetness and light but, honey, you weren’t exactly in a Soviet gulag.

But back to Mr. Arlen. I am quite fond of the fellow because, as mentioned before, hubbah. Also, he could be excellent when he had something to work with. I loved him in Feel My Pulse, for example. Okay, so maybe he was no John Barrymore (wasn’t one John Barrymore enough?) but he could definitely get the job done.

What I enjoyed about Arlen’s performance in The Four Feathers is that he really captures to forlorn flavor of a character whose worst nightmare has come to life. More than any other version of the film that I have viewed so far, the script and Arlen put across the real reason for Harry’s on-the-edge risk-taking courage. Simply put, the worst thing that could possibly happen to him has happened. He has nothing more to lose. I feel that this fatalistic and suicidal aspect of the character is not communicated as directly in subsequent versions.

The theme of suicide runs throughout the picture. Harry’s father speaks of goading a subordinate into the act by delivering a white feather. The memory of the scene is still strong when Harry’s friends and Ethne hand over their feathers and the message is clear: This is not just a condemnation of Harry’s behavior, it is an explicit message that he must end his own life. The message is repeated when Harry’s father directly orders him to shoot himself.

Harry’s subsequent actions reflect the recklessness of a man who already considers himself dead. He consistently goes into danger without an exit strategy.

The entire second act of the film is taken up with Harry’s daring (if poorly-planned) rescue of Captain Trench. You will recall that Trench was captured by the enemy. (The Hadendoa people, to be exact. Yes, I realize that almost every movie refers to them as the Fuzzy-Wuzzies but let’s start a new trend, hmm? You know, calling people what they like to be called. Hadendoa.) At this point in his career, William Powell was beginning to make headway but it was sound film that really made him a star. What a voice!

Powell had co-starred with Arlen several times before. He had played a villainous rum-runner in Feel My Pulse and a villainous Arab chieftain in She’s a Sheik (in which Bebe Daniels took the Valentino part and kidnapped Mr. Arlen). I think I detect a trend. Powell had been a seducer of Gishes, murderer of Gatsbys (he was the original George Wilson), and had played all-around bad/ambiguous/shady guys of every description. 1929 was a banner year for him because the release of his Philo Vance detective films assured his jump from playing villains to catching them in their wiles.

Next to Arlen’s Harry, Powell’s Trench is the most fully sketched character in the film. Trench is the one who discovers Harry’s deception and reveals it to their mutual friends. He is responsible for the four feathers. In the karmic world created for this film, he is also the one to suffer the most. Durrance gets a fever and Castleton gets ambushed but Trench is captured, tortured and enslaved by the enemy.

As the ringleader of the white feather brigade, Trench’s acknowledgement of his error means the most, both to Harry and in terms of the smooth narrative. It is a shame that it is resolved before the third act. The final act of the film is taken up with Harry replacing the wounded Durrance in an isolated fortress, putting down a mutiny with force of will and then saving Castleton from a Hadendoa ambush.

(Spoiler for this paragraph.) As for Ethne, she and Harry easily forgive one another once he returns to England as a hero. I felt that the ending was a bit of a false note. The film took the story into very dark places and it just seemed unlikely that all would be smoothed over so easily. I know, I know, Hollywood. Still, I would have liked a bit more internal conflict.

Arlen and Powell really shine in this film. Clive Brook and Fay Wray are underused, in my opinion. One sleeper performance is George Fawcett as Harry’s father. He is just splendid as the stubborn old soldier who cannot understand the damage he is doing to his sensitive son.

The Four Feathers is also acclaimed for its wildlife scenes and rightly so. According to Ray Morton’s book King Kong: The History of a Movie Icon from Fay Wray to Peter Jackson, Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoedsack traveled to Africa in order to capture the shots of baboons, hippos and camels that would add great authenticity to the picture. Landscape and native peoples were also included.

Cooper and Schoedsack then returned to California to shoot footage with the Hollywood stars. Apparently, producer David O. Selznick was dissatisfied because he called in Lothar Mendes, a Paramount staff director, to shoot additional scenes. The two documentary directors were displeased at what they considered dumbing down of their film. However, we must remember that the pair had never made a true narrative film. Likely, the additional footage was used to clarify plot points, etc.

I should also note that the scenes in the movie that are likely to strike a sour note with modern viewers (well, other than Noah Beery’s obnoxious slaver character) are the lingering closeups of the African extras (doubtlessly under director’s orders) glaring menacingly into the camera. The native Sudanese (both opposing and belonging to the British army) are presented as barbarous, dangerous children.

The Four Feathers also sinks into cliché with its treatment of Richard Arlen’s young sidekick. Let’s see if you can fill in the blanks. Hero meets kid, makes friends, takes him on as a mascot. Hero gets into trouble, mascot saves him… What comes next? If you answered “at the cost of his own life and then he dies in the hero’s arms” then you are right! Have a digital cupcake!

In spite of these issues, The Four Feathers is an excellent adventure film. It moves along at a speedy clip, it features some remarkable location photography and it presents the hero’s moral dilemma in a surprisingly dark manner. It’s definitely worth tracking down.

Movies Silently’s Score: ★★★★½

Where can I see it?

There is a very faded and battered film circulating around that goes in and out of print. I hope there is a better version out there somewhere because this one is, frankly, almost unwatchable. It is a testament to the film’s quality that I was able to stick it out in spite of print issues.

The 1939 version of The Four Feathers is sometimes described as the definitive take on the tale. It boasts color cinematography that is so good that it was lifted for other films even decades later. Can the silent version stand a chance? That’s what we are going to find out right now.

The Talkie Challenger: The Four Feathers (1939)

The famous Korda family, Hungarians by birth, took on this most British of tales in 1939. The result is a revered and beloved classic, considered one of the jewels of one of the most glittering years in classic cinema.

As with most versions, the film opens with the hero, Harry Faversham (as opposed to Feversham), listening as his father and his old war buddies relive the glories of Crimea. General Burroughs (C. Aubrey Smith) demonstrates how he personally won the war with a pineapple and some wine. What stands out to young Harry is the talk of cowardice and the ostracism that awaits those deemed unworthy of their uniform.

The old soldiers fail to notice the boy’s distress but Dr. Sutton (Frederick Culley) realizes that something is wrong. He tells Harry that he will be there to help him if he ever needs assistance.

Years pass, Harry (John Clements) grows up and enters the army. He never had any other option, really. He is engaged to General Burroughs’ daughter, Ethne (June Duprez), and is the best of friends with Captain Durrance (Ralph Richardson). Durrance is also in love with Ethne but he will not step on Harry’s toes and contents himself with being best man.

Harry’s father has passed away and our hero abruptly resigns his commission. The timing is suspicious as Harry’s regiment had just received orders to set out for Sudan. Durrance and Harry’s other friends suspect the worst.

As it turns out, Harry just timed his resignation badly but he refuses to back down. He has given his entire life to duty and he wants out. His disgusted friends send him three white feathers and, as Ethne is too nice to do it herself, Harry takes one from her fan.

The regiment departs for Sudan but Harry stays in England and stews over his motives and behavior. A long talk with Dr. Sutton makes him realize the root of his fears and he makes a decision. He is going to go to Sudan, prove his bravery and make every one of his friends take back their feathers.

As you can see, there is considerable difference between the silent and the talkie. Let’s see how these differences stack up.

Harry: Richard Arlen and John Clements had very different takes on the character. Some of this was due to the scripts of their films and some was due to their acting style. Both men were the same age when they played the part (they were twenty-nine when the movies were released) but Clements comes off as the older and more mature of the two. The accusations of cowardice are the result of his timing his departure badly. He has doubts about traipsing the world looking for conquest but his decision is calm. He only realizes that there is something more (fear of fear) when the feathers arrive. Arlen, on the other hand, makes his decision to resign when he is called to war. He leaves in a panic, terrified of proving himself to be a coward.

Arlen’s approach is much more understandable to the modern viewer. While the 1939 version deals with matters of honor, the 1929 version focuses more on the “go kill yourself” undercurrent. The honor system of Victorian England is now as alien to us as starched collars, dressing for dinner and romanticizing consumption. But being told by your nearest and dearest that you are better off dead? That is a sting most anyone can understand.

Both takes on the character are interesting and both are understandable in the context of their respective films. It’s a matter of taste but I preferred the more emotional angle from Richard Arlen. The silent is darker in its outlook and I enjoyed the dramatic flair for Harry. A point to the silent.

Ethne: June Duprez is lovely but she lacks the steel that is required to make Ethne’s rejection sting. While Fay Wray breaks off a white feather for Harry with little hesitation, Duprez hems and haws and it is finally Harry himself who takes the feather from her fan. This difference also illustrates how far the portrayals of women in films had regressed between the silent and the post-Code talkies (yes, I am aware this in an English production but they were as aware of the Code as Americans). While Fay Wray could show Harry the door with the forcefulness of a soldier, Duprez is forced to meekly allow him to flounce out on his own. A point to the silent.

Supporting Cast: C. Aubrey Smith walks away with the sound film, there’s no denying it. He has the best scenes and the best lines and knows exactly how to use them. Come on, when did Smith not walk away with whatever film he appeared in? However, the silent boasts of a very good turn from William Powell and the forgotten George Fawcett is excellent. It’s a close shave but I am narrowly calling this one for the silent.

Cinematography: While the black and white photography of the silent is gorgeous (at least as much as is viewable with the poor print), the scale and scope of the talkie gives it the advantage. The talkie’s design and cinematography are justly famous. A point to the talkie.

Portrayals of Sudanese and Egyptians: While it does show authentic tribesman, the silent film falls into racial clichés and Noah Beery’s slaver character is quite offensive. The sound film, while definitely pro-Empire, has a much more balanced view of the enemy tribes and native allies. Some British soldiers are shown being less than gentle with their native servants and laborers, a fact that only the most naïve or jingoistic would deny. A point to the talkie.

Adaptation: The talkie falls into the Sudan-to-tea-tables structure that made the book so deadly dull. While there is excellent acting to be had, I really prefer the intensity that comes from leaving the story in Sudan where it belongs. A point to the silent.

And the winner is… The Silent!

In a startling upset, it is the forgotten 1929 version that emerges as the winner in this conflict. While the sound film is well-acted, well-shot, well-made in every conceivable way, it did not move me or interest me as much as the silent.

In fact, it is the very format of silence that helped ensure its victory. While the talkie uses confidants to help us understand Harry’s motives, the silent film gives us access to Harry’s thoughts through well-chosen title cards. This also serves to make his trials more solitary. He has no ally for a good part of the film.

I also appreciated the darker tone of the silent. While the talkie’s feather scene is dramatic and acted very well, the silent’s explicit call for suicide makes Harry’s mission all the more urgent. The silent also stays in Africa once Harry arrives. There are no constant scene changes back to England. This happens at the expense of Ethne’s character but it makes the action more driving.

While both films are excellent, the silent is the one that I enjoyed the most.

I’m with you in the Arlen hubbah brigade, but have yet to see the ’29 version. I’m overly familiar with the ’39 movie as it used to pop up regularly on TV here in Toronto and it is as if I felt duty-bound to watch it every time. The color is breathtaking. I can still feel the heat as if I were in the desert. Again, you have opened my eyes to a film I must see. Thanks.

So glad you enjoyed it! I really hope the ’29 version has a better print lurking somewhere. It deserves better presentation.

I picked up a DVD-R copy of the ’29 film from the now-defunct VintageFilmBuff.com. It was mastered directly from a 16mm print with the original music soundtrack. It’s not perfect, because there’s a black vertical bar running down the right side of the screen that cuts off a sliver of the picture, but all in all it’s perfectly watchable. However, I’d LOVE to see a proper restoration of this excellent film.

Me too! I have heard tell that Warner has a pretty good 35mm print. Here’s hoping it eventually gets released to the public.

Fritzi, such a great and well-rounded selection. I’m so glad that you joined in, thank you! Both are such incredibly well done, as are your reviews!

Thank you and thanks for hosting!

I’ve not seen the ’29 or ’39 versions, which I should. I did, however, see the Heath Ledger version which I unexpectedly liked. However, the 1929 version sounds like a real gem, and I will drop everything if I have the chance to see it.

Yes, I was very pleasantly surprised by it. Plus, it’s a chance to see William Powell just at the edge of stardom.

Williamm Powell alone would be worth it, in my opinion.

I really enjoyed the 1939 version, so I will have to make an effort to try to watch the 1929 version. I will say that C. Aubrey Smith’s performance has been stuck in my mind since I saw it, just a wonderful performance.

Yes, he was really splendid 🙂

As a Brit I can confirm there were no wrongs associated with the British Empire, there’s just something funny with everyone else’s point of view 😉

Great post Fritzi, I’ve only seen the ’39 version so it was a great introduction to the history of the movie. Will keep an eye out for this and the ’29 version.

Thanks so much! Yeah, the ’29 version is really a hidden gem.

Fritzi – sorry to be so late to the commenting party. This is such an excellent, in-depth post – thanks for adding so much to the blogathon! Great idea, to do a grudge match, silent vs. talkie review! I must admit a bias to the talkie version, mainly because I haven’t seen the 1929 silent yet. All you had to say was “William Powell” and I’m there. Will definitely be seeking the 1929 version out one day soon.

Thanks so much for hosting. So glad you enjoyed!