A strike in New South Wales was caught on film and turned into a feature-length documentary. These fragments are all that remained after the censors got through with it.

Home Media Availability: Stream courtesy of the NFSA

S-T-R-I-K-E

Arthur Charles Tinsdale had been trying to break into motion picture production for years. He had been importing foreign fare for Australian audiences and the distributor-to-producers path was already being followed elsewhere, so why not? As always in filmmaking, funding was a challenge and, for his 1917 comedy A Laugh on Dad, he hit on the solution of a subscription model, basically crowdfunding. Oscar Micheaux would follow a similar path in the United States. Tinsdale added a bonus incentive: buy one-hundred two-shilling shares in the picture and earn the right to appear on the screen as a film actor.

Critics sniffed at A Laugh on Dad upon its 1918 release, declaring that the humor was of the vulgar kind once popular “in certain music halls of English industrial towns” but it proved popular enough for a sequel and Tinsdale continued to try to break through, never fully succeeding. However, his other production of 1917 would prove to have lasting historical staying power.

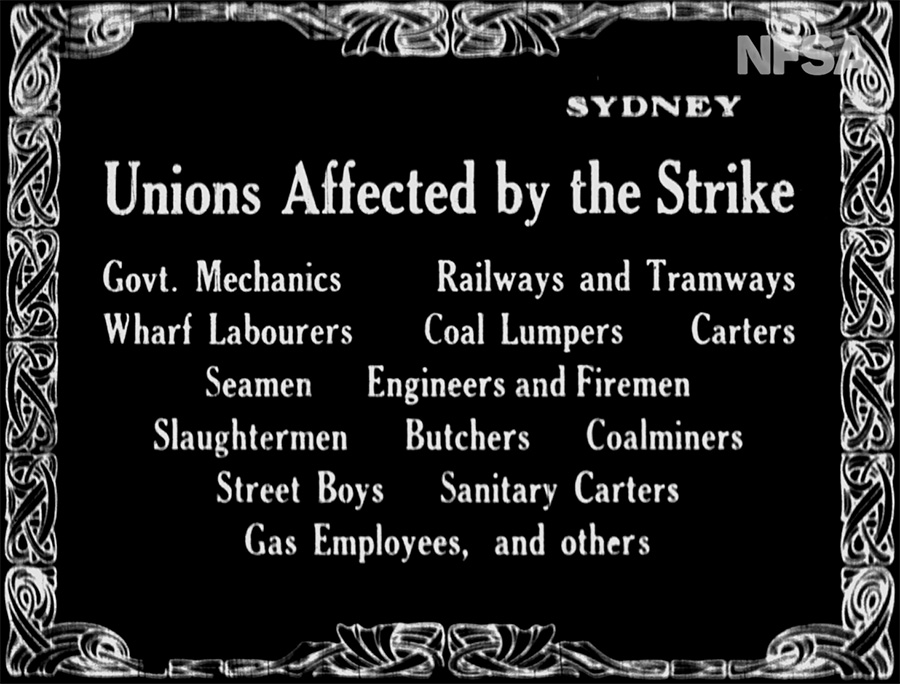

The railway workers in New South Wales walked off the job in August of 1917 and were quickly followed by coalminers and factory employees. The strike spread with tens of thousands of workers marching for better conditions. Management brought in scabs, which were plentifully available thanks to a poor economy, and the strike was broken. Returning workers faced retaliation in the form of demotions, pay cuts and blackballing.

While the strike was not successful, it was the largest pro-labor action in Australia to date and the 1919 Seaman’s Strike learned lessons from the failure of the Great Strike. They successfully blocked scab labor, shut down Australian shipping and won most of their demands. The Great Strike also politicized its participants, with train driver Ben Chifley going on to serve as Australia’s 16th prime minister.

But we’re here for movies and so we won’t be heading into the deep waters of the twentieth century labor movement. As you probably guessed, Tinsdale, who had relocated to Sydney, was conveniently on hand at the epicenter of the Great Strike and no silent era filmmaker was going to let free material pass him by.

Tinsdale’s stated purpose was to capture both sides of the strike, which was nearing its end when the picture was released in October of 1917. The picture ran for about an hour and was shown on the big screen… once. It seems that October 1917 premiere was the first and last time The Great Strike was shown in its original form. Politician and scab fan Walter Wearne pushed for severe cuts to the material and The Great Strike was re-released in a pared-down form as Recent Industrial Happenings in NSW.

For nearly a century, it was believed that only twelve minutes of the original film survived but a six-minute reel was later discovered, bringing to total available footage to fifteen minutes. The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia reassembled the scenes based on the original order published in a synopsis. (Scene-by-scene synopses in print media were common at the time, even for non-fiction films, and, while they sometimes differ from the final product, they are generally pretty reliable.)

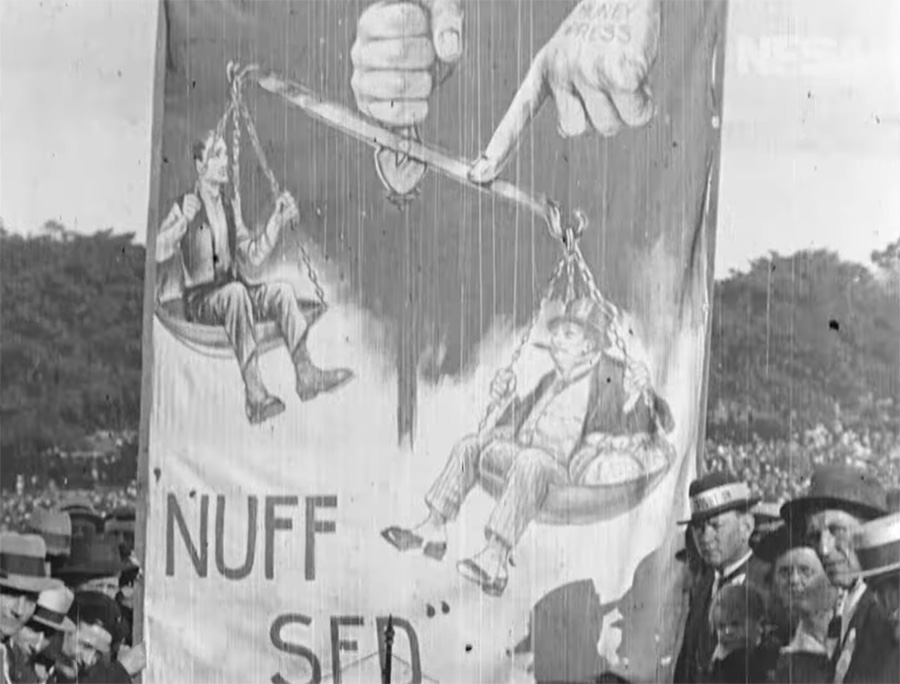

The surviving footage opens with “trouble brewing” at a labor meeting and then shots of laborers marching with signs and banners. Title cards relay the songs being sung (possibly as a cue to movie theater accompanists) and the strikers cheerfully tip their hats to the camera. These scenes take up a third of the surviving footage and convey the large crowds that turned out for the marches. And, as always, seeing normal people in everyday streetwear as opposed to studio-curated costumes is always a pleasure.

(I have to admit that I got turned around and was confused by the relatively heavy coats in August for a moment, but then I remembered that this takes place in the southern hemisphere and August is late winter.)

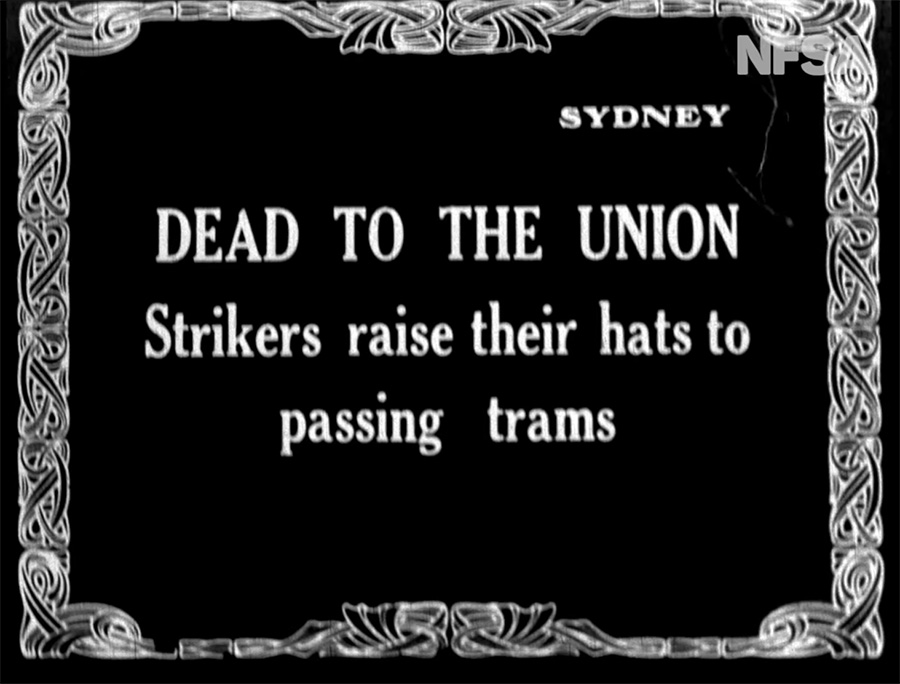

We are briefly shown a shot of an idle shipyard and then the footage cuts to labor leaders being released on bail, arrested as part of a government pressure tactic. The strikers sarcastically raise their hats to passing trams, manned by scabs, and then the footage shows the other side of the coin: the “volunteers” working the jobs left empty by the striking workers. There is considerably less merriment on this side, a few waving hats but mostly grim stares. (An armed strikebreaker had murdered an unarmed striking laborer, this was a life or death situation.)

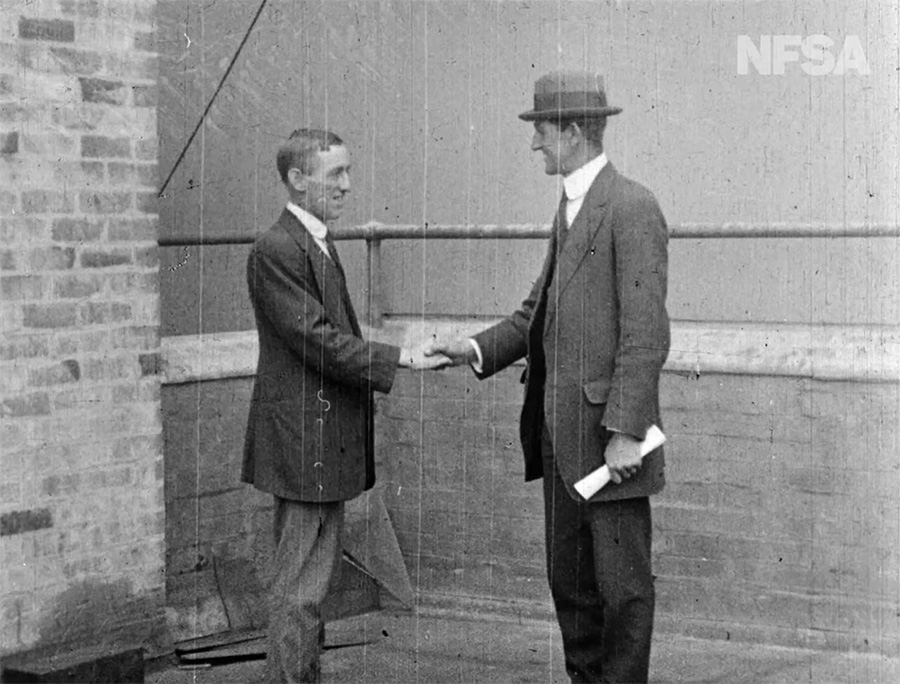

Tinsdale attempts to wrap up the film on a positive note, showing the unions accepting a settlement (a few glowering faces in the crowd indicate that all was not well there) and concludes with a dad joke about the umbrellas going on strike too during the ensuing rainstorm. Throughout, he clearly attempts to keep things light and avoid controversial topics but that, of course, just makes us wonder what the cut footage must have been like. It’s likely that such material is lost forever but then again, the additional five minutes were only recovered in 2016, so never say never.

Tinsdale sailed for England in the 1920s, returning to Australia to screen his new Gallipoli film (not to be confused with The Spirit of Gallipoli, released around the same time), a collection of newsreel footage that ran well over two hours and is now lost, as are most of Tinsdale’s other films.

While The Great Strike is clearly of great interest to anyone who studies the labor movement, it is a ghostly attraction to students of history generally. The street scenes filled with long-dead people, the cultural references that just miss being comprehensible in the modern world, the push and pull of Tinsdale trying to craft a crowdpleasing documentary out of the most controversial of events and the unspoken conflict with government censors… It’s deeply human window into a lost time.

Where can I see it?

Stream courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.