A short film depicting the story behind the Edward Burne-Jones painting, designed to class up the joint in Hollywood but mostly remembered for launching the career of Mary Astor.

Home Media Availability: Available digitally from Milestone.

Barefooted came the beggar maid

Movies were the popular entertainment for the American public by the 1920s and there was always a demand for new material. Magazine stories were sold as quickly as they were published, novels from great literature to trash would be adapted with great fanfare, even a middling Broadway run could yield a film deal.

The Beggar Maid went even further afield, adapting both King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid by Edward Burne-Jones and its inspiration, the short poem by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (which was itself adapted from a much older ballad). All this and Mary Astor too! (Just fifteen and in one of her first movie roles.)

The film is a brief two-reeler with a simple plot: The Earl of Winston (Reginald Denny) is visiting his good friend, the painter Burne-Jones, for some advice. The Earl is in love with his gardener’s daughter (Mary Astor) but he can’t be sure that marriage would be a good idea. Burne-Jones settles in with some Tennyson and, inspired by a poem, visualizes a scene of a king falling in love with a beggar maid at first sight and immediately making her his queen. The scene is so vivid that Burne-Jones decides to play matchmaker and artist at the same time.

The gardener’s daughter (whom I will call Mary for the sake of readability) lives with her sickly musician brother in a cottage. Her brother and neighbor are disturbed by the Earl’s attentions. After all, he risks nothing but her reputation is at stake. Burne-Jones calls and asks her to model for him. Mary agrees and is surprised to see that the Earl has also been engaged to model as the king. Love blooms but the brother, concerned that the Earl is only playing and will not marry his sister, tells her that she must cut off the affair.

Things look hopeless for the pair but then Burne-Jones steps in once more with artistic intervention, delivering both a masterpiece and a happily ever after for the couple.

The Beggar Maid is a light, pleasant picture that goes down easy without too much conflict. It’s important to understand that the picture would not have been viewed in isolation as the solo entertainment of the evening but rather mixed into the theater’s program of other films and even live performances at larger venues. For example, the Mark Strand in Brooklyn had the following program:

- A patriotic overture consisting of film, orchestral music, interpretive dance and tableau

- A topical review of current events

- A special live musical prologue for The Beggar Maid. Per the theater: “Artist studio interior with artist at easel sketching “Beggar Maid,” model seated on raised dais. He (George Dale, tenor), sings Lewin-Harling’s “There’s Sunshine in Your Eyes.” The prince (Walter Smith, raconteur) appears and recites Tennyson’s poem of same title.” (Such fanfare for a short was unusual and commented upon at the time)

- The Beggar Maid film proper

- A live college-themed musical prologue to the feature

- Feature: Charles Ray in Two Minutes to Go

- Opera selections from Bizet

- Tony Sarg silhouette animation

- Organ Solo

Critics praised the direction, design, and particularly Mary Astor as a rising star. At last, a truly fresh idea for the screen! Within a few years, both Astor and Reginald Denny would be major stars and box office darlings.

The Beggar Maid doesn’t shed any particular light onto the creative process of Burne-Jones or any other artist, really, and that was by design. Portrayals of the creative process in films have always been simplified: A “Eureka!” moment and a montage of furious typing yields a novel. A daydream yields a poem. And the right model and story yields a masterpiece painting.

Gotogo, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

In fact, Burne-Jones struggled with The Beggar Maid for decades. His initial attempt in 1862 lacked life, dynamism and contrast. Its narrative was opaque and there was no particular sense of place. He kept poking around the topic before tackling it again in earnest in the 1880s, using multiple studies to plan out lighting, composition, draping. He agonized over the design of the heroine’s dress (it had to look poor but also becoming enough to attract the king) and produced nude studies of the male model for Cophetua (I can’t imagine that particular sequence making it through the censors).

In short, King Cophetua and the Beggar Maid was the culmination of all the skill and experience that Burne-Jones had built between 1862 and 1884 and it all shows in the finished work. He came back and made the painting he had not been ready to produce before and that is extremely exciting… on the page.

On screen, an authentic portrayal of the process would be a lot of sketching, a lot of pacing, a lot of fiddling with light sources and drapery, a lot of dress designs… a lot of mundane labor that is the backbone of a professional artist’s working life but deadly dull on the screen. So, a more romanticized version had to be concocted because accuracy is all well and good but movies need paying customers. A glowing romance-within-a-romance was just the ticket in the 1920s (and worked again to a certain extent in the 2000s with an added dose of Colin Firth).

The risk with romanticizing, of course, is that it spreads the perception of artists as naturally talented beings who wait for inspiration to strike (or the right muse to come alone), minimizing how much time, hard work and practice are poured into a piece of art. “Talent is perspiration,” as Kate Sanborn wrote.

So, again, I don’t think this film meant to realistically portray Burne-Jones at work. Rather, it was meant to create a story that the viewer would attach to the artist and painting, thus spurring interest in both and, as strategies go, this isn’t a bad one. However, the film also had an unexpected ace in the hole, its leading lady.

While Tennyson’s poem describes a dark-haired woman, Pre-Raphaelites gotta Pre-Raphaelite and Burne-Jones gave the maid auburn hair. And this is where Mary Astor enters the story. Astor wrote in her autobiography that, after a few false starts in her film career, photographer Charles Albin had arranged for her to audition for the lead role of The Beggar Maid because she looked the part, right down to her auburn hair.

Astor marks this as the true start to her career, her first time seeing her name in lights and the film that finally opened industry doors for her, which would have been unusual for a dramatic two-reeler of the time. After all, features were dominating the industry and two-reelers were just a piece of a larger program with one- and two-reel breakout stars mostly in the comedian category. However, The Beggar Maid was no ordinary two-reeler, it was part of a long and proud tradition of filmmakers trying to bring Capital A Art into the movies.

The Beggar Maid was intended to be the first in a series of films meant to dramatize the creation of famous paintings and was a continuation of the film industry’s attempt to burnish its reputation as a force for art and education. You can see echoes of this in titles like The Assassination of the Duke of Guise (1908), which engaged major stars of the French stage and featured a bespoke score by Camille Saint-Saëns. In 1922, Dudley Murphy and Adolph Bolm oversaw Danse Macabre (based on the Saint-Saëns piece of the same name), which was meant to kick off a series of filmed visual poems set to classical pieces and synchronized with special player piano rolls.

The famous painters series was a product of Triart. Isaac Wolper was president and had previously attempted to adapt poetry to the screen (as well as reactionary anti-Bolshevik propaganda by Thomas Dixon) but the painting series had major names attached. Herbert Blaché was named director with art direction by photo-illustration superstar Lejaren Hiller. The series touted an advisory board that included Charles Dana Gibson, Daniel Chester French, Louis Comfort Tiffany, Robert Ingersoll Aitken, Edwin Blashfield, as well as names associated with the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Critics, educators and religious leaders were ecstatic about the series and The Beggar Maid in particular. It was given the seal of approval by some religious leaders for church screenings and was featured as part of the curriculum of Columbia University’s motion picture course.

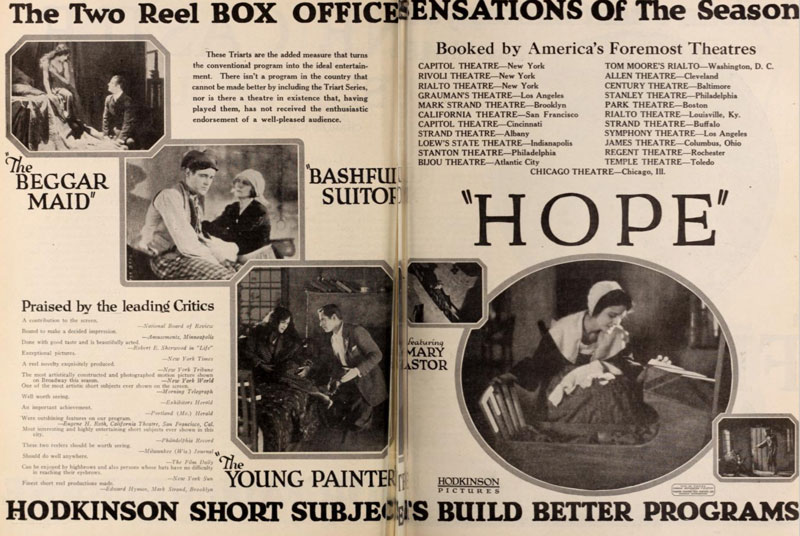

While the series was supposed to produce twelve films in twelve months (a realistic schedule for the period), only four were eventually released: The Beggar Maid, The Bashful Suitor, The Young Artist, and Hope. Three of the films starred Astor. Reading between the lines, it seems that the company was hit with multiple blows in 1922: Astor was wooed away by Paramount, Blaché was undergoing a messy matrimonial and business divorce from wife-partner Alice Guy, and Triart president Wolper died suddenly.

Hope (based on the 1886 painting be George Frederic Watts) was directed by Hiller instead of Blaché with Hiller as artistic director. Advertisements for the picture make no mention of either man but tout the participation of Astor, reflecting her growing stature as a film star. There was talk of reviving the concept under the Truart brand but the bloom seems to have been off the rose by then.

Judged within its original context, this is a good film. It’s an attractive, pleasant and classy piece of infotainment that would have slotted easily into whatever else the theater was screening at the time. On its own, it’s a bit bland and its low budget reveals itself at times, especially in the sequences of the king’s palace. However, it’s a good-looking picture, especially when the scenes shift to the outdoors.

Astor and Denny do what they can with the material, which mainly calls on them to look pretty and romantic, with their natural charisma handling the rest. Fans of either star will be interested in seeing this as it was the root of Mary Astor’s stardom and a rung in the ladder for Denny’s (both stars’ careers benefited from a connection to John Barrymore, unrelated to The Beggar Maid).

Where can I see it?

Rent or purchase digitally from Milestone.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.