A classic tale of Boy meets Girl, Boy proposes to Girl, Boy accidentally joins the Navy and is now out at sea for three years. Harold Lloyd plays a nervy rich kid who finds more adventure than he bargained for.

Home Media Availability: Released as part of an out-of-print Lloyd collection.

Anchors Aweigh

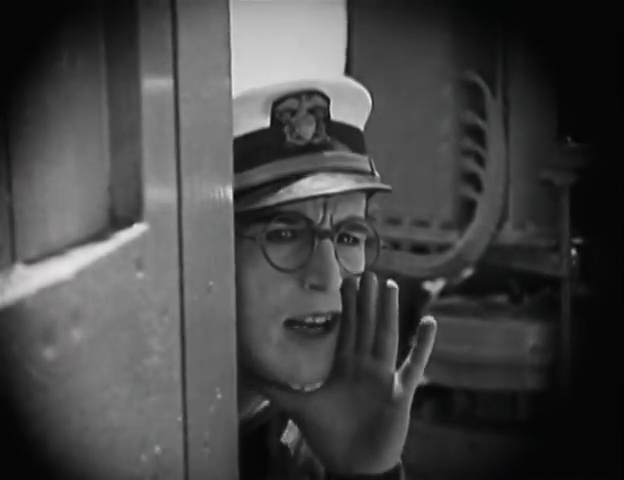

Harold Lloyd was once again looking for love in A Sailor-Made Man, his first foray into features. Lloyd’s history in the movies is about as well-known as any major star but to quickly recap: he started out on the bottom rung with small parts, found some success in the Lonesome Luke series (a mustachioed fellow with too-small clothes in the usual slapstick mold), but really hit it big when he donned glasses and morphed from a slapstick man to a rom-com lead with additional hair-raising stunts.

Lloyd’s films were still being produced by Hal Roach when A Sailor-Made Man was released and the film represented a step up the Hollywood ladder for both men, with Lloyd becoming a box office name and Roach a producer who could do more than shorts.

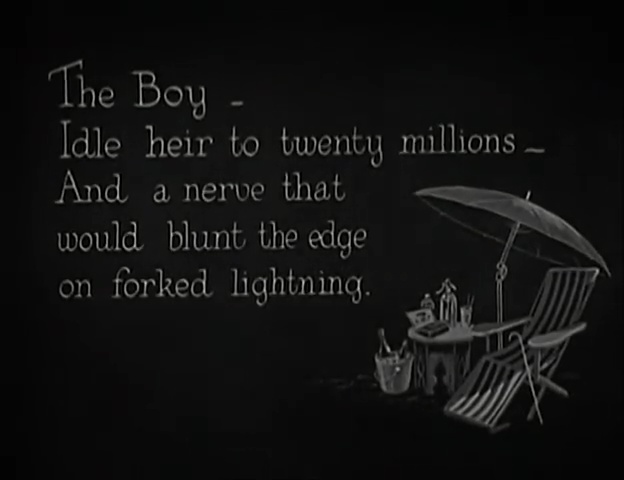

As usual, Lloyd is credited as the Boy and he is an obnoxiously brash heir who strolls through life, and in this case a tony resort, sticking his nose where it is not wanted. The belle of the hotel is the Girl (Mildred Davis), who is averaging “six proposals a day– including Sundays and holidays.”

The Boy strolls up and proposes on the spot, she tells him to ask her father but she is already smitten. Her father, on the other hand, wants no lazy lounge lizards in his family and insists that the Boy make something of himself. The Boy takes this literally and walks into the first opportunity he sees: a Navy recruiting office.

Meanwhile, the Girl’s father arranges for a world cruise and she excitedly invites the Boy. He returns to the recruitment office to rescind his generous offer to join the Navy but, as it turns out, the armed forces don’t accept take-backsies on enlistment and he is marched off for his three-year deployment at sea.

The Boy dreams of promotion but is still just a seaman. However, he does befriend the lovable lunk Noah Young and engages in assorted shipboard hijinks before the crew is granted shore leave in Khairpura-Bhandanna, where the Girl’s yacht is also docked.

By the way, The Sheik had been a major 1921 hit and might be the first guess for inspiration but both the town scene and palace sequence in the film reminds me very much of Kismet (1920), a surprisingly good adaptation of the stage play (not yet a musical). The set design is similar in appearance, though I will admit that the Orientalist look was popular across Hollywood generally, but Kismet especially featured deep indoor bathing pools as both design elements and murder weapons, so I think it is probable that Lloyd or his writers had at least seen the picture.

The film’s plot picks up when the Maharajah (Dick Sutherland) spots the Girl and arranges to have her kidnapped and added to his harem but, of course, he didn’t count on the pluck and tenacity– not to mention acrobatic skills– of the Boy!

So, that’s A Sailor-Made Man. Lloyd and Davis are cute, Young is funny, Sutherland lays his performance on as thick as his pancake makeup but in general, everything works in the hands of regular Lloyd director Fred Newmeyer.

Comedy shorts in general tended to be rougher and have fewer moral lessons than features and A Sailor-Made Man is a bit betwixt and between, with the length of a feature but the attitude of a short. Lloyd’s character succeeds (it’s not really a spoiler, I can’t imagine any viewer entertained the possibility that he would fail or perish) because of his obnoxious brashness, the same fatal flaw he exhibited at the beginning of the picture, doesn’t really grow or change beyond learning to salute an officer.

I am actually fine with that in this picture. The action is so extreme that Lloyd’s cartoonish take on his persona works. Everything else is exaggerated, so it’s fine for him to be exaggerated too. And since Mildred liked his attitude from the start and she is the one who wants to marry him… a successful outcome for all involved.

A Sailor-Made Man doesn’t have a complete story so much as a string of loosely-related incidents, like isolated shorts woven together. Again, this was typical for both Harold Lloyd films released earlier under the Hal Roach banner and later Hal Roach releases with stars like Charley Chase and Laurel and Hardy. In practical terms, it was probably a way to split a two-reeler into two one-reelers, a three-reeler cut down to a two-reeler, etc. and it was also a way to use two or more one-reeler scenarios in one go. Whatever the reason, I am so used to it, from Fluttering Hearts to A Chump at Oxford, that I don’t really see it as a flaw. (Though I do think a few scenes of Lloyd being humbled during his early enlistment wouldn’t have been amiss.)

Lloyd’s most famous films had smoother, more sophisticated plotting and a clear moral but I do have a certain affection for the brasher, more chaotic Harold. For example, he spends much of the first half of Haunted Spooks attempting suicide after losing “another one of the only girls I ever loved!” This is never addressed again and he marries Mildred Davis and heads to a haunted house. It’s very much the “if you can’t convince ‘em, confuse ‘em” school of comedy and I am convinced. That being said, your mileage will very much vary and if you like the more civilized Lloyd of Girl Shy and Safety Last, A Sailor-Made Man will be a bit of an adjustment.

A Sailor-Made Man is four reels long (or about forty-six minutes in the official release cut from Lloyd’s estate) and therefore qualifies as a feature film, with an equivalent runtime to an hour-long U.S. network program sans commercials. The story, as told by Lloyd in an interview, was that A Sailor-Made Man was intended as a two-reeler but they decided to keep filming since they had so much material. While Lloyd was not technically authorized to make a feature (four reels being the bare minimum length by industry standards), both he and Charlie Chaplin had been making three-reelers successfully, so the jump was not quite as dramatic as the story indicates. In fact, a couple of Lloyd’s 1921 three-reelers were only a few hundred feet shorter than A Sailor-Made Man.

I am always a little suspicious of these Eureka! tales in in the movies. Even if Lloyd and Hal Roach weren’t officially planning to make a feature, I am sure the thought had crossed both their minds that longer films were a sign that one had arrived in Hollywood. And with Fairbanks a converted costume swashbuckler man, having scored a hit with The Mark of Zorro and following up with The Three Musketeers, there was an opening in the Energetic Young Man Romances With Stunts feature film category. (Though it should be noted that Wallace Reid was active in that space.)

Several books on Lloyd frame the film’s release as him jumping ahead of Chaplin and Buster Keaton, indicating that a comedy feature was completely new. However, comediennes like Constance Talmadge and Marion Davies had been making comedy features for years, Mary Pickford had been starring in dramedies since the start of her feature film career that probably would have been called Chaplinesque if she were a man, two of the earliest American comedy features, A Florida Enchantment and Tilly’s Punctured Romance (both 1914), heavily featured women. This also overlooks Douglas Fairbanks, whose breezy modern pictures of the 1910s were essentially a blueprint for Lloyd. Silent film history does tend to overemphasize slapstick, which seems to be the case here.

In any case, no matter how it ended up being made or whether it was a cinematic first for anyone but Lloyd, audiences of the day were enthusiastic about lengthier Glasses character comedies and A Sailor-Made Man earned back its budget six-fold, assuring that the comedian would continue to give the public what they wanted.

By the way, as was often the case with Hal Roach-produced films, the title of A Sailor-Made Man was a play on an otherwise-unrelated popular pop culture element, in this case, the hit play A Tailor-Made Man, a curiously anti-labor tale of a tailor who fakes it until he makes it, breaking up strikes and marrying into an industrialist family. (It was based on a Hungarian play by Gábor Drégely– Hollywood loved its Hungarian source material.)

Charles Ray, who was trying to build his own career after becoming a star in the country bumpkin genre during the 1910s, brought A Tailor-Made Man to the screen in 1922 but it doesn’t seem to have been particularly successful. I wonder if the mammoth success of A Sailor-Made Man caused some confusion or stole thunder from an adaptation of the original.

A Sailor-Made Man hits a nice, sweet spot for me as a big fan of the old Roach house style and someone who prefers a shorter Lloyd, generally. It’s what I like but more of it. Your own opinion will depend on your preference but give it a shot.

Where can I see it?

A Sailor-Made Man was only released on physical disc media as part of the now out-of-print Harold Lloyd Collection Volume 3. As of this writing, it is streaming on the Criterion Channel. The official release has a fine score by Robert Israel.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.