And now for something completely different! When I review silent movie books, I generally focus on books about silent films themselves and the men and women who made them. For a change, I am going to cover some books that inspired silent films. Let’s start with the quintessential swashbuckler, The Prisoner of Zenda.

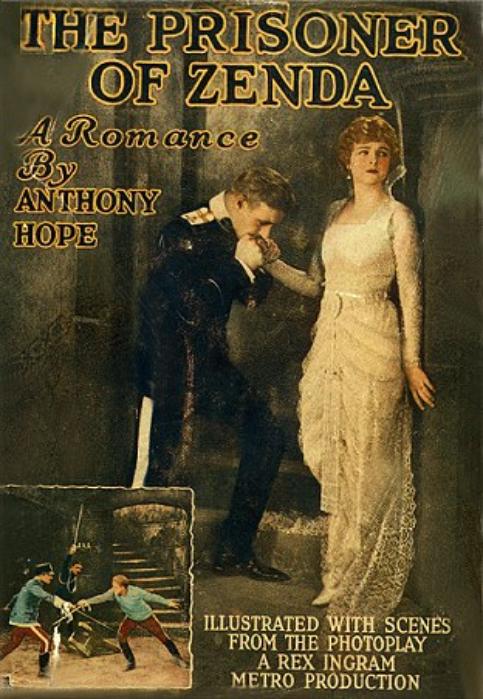

My copy of the book is a Penguin Classics edition, which also contains its direct sequel, Rupert of Hentzau. However, since the novel was written in 1894, it is in the public domain and may be downloaded for free. The edition I found on archive.org has illustrations by Charles Dana Gibson. And there is a splendid free public domain audiobook courtesy of LibriVox. (Seriously, I’ve bought audiobooks that aren’t half as good.) I have to confess that I also covet the leatherbound edition and may splurge one day.

What is it?: A tale that has been told before and has been retold again but has rarely been told better: An Englishman named Rudolf visits a European kingdom and discovers (through an indiscretion on the part of his great great great great grandmother) that he is a dead ringer for the king. This comes in handy when the king is kidnapped by his evil brother and Rudolf must keep the conspirators at bay by occupying the throne.

My favorite part: The rakish villain, Rupert of Hentzau. While he is not the main bad guy (that would be Duke Michael, the afore mentioned evil brother), he is by far the most memorable. The book describes him like this:

Once again he turned to wave his hand, and then the gloom of the thickets swallowed him and he was lost from our sight. Thus he vanished reckless and wary, graceful and graceless, handsome, debonair, vile, and unconquered.

Rupert proved to be so popular that Anthony Hope’s sequel was named for him.

My least favorite part: The books has a bit of snobbish tone that gets trying very quickly. Also, Hope has the habit of introducing too many characters. Michael has six henchmen when only one or two would to the job just as well. Rudolf’s English friends and family are carefully introduced at the beginning only to disappear and never be heard from again in the book.

Influence: The book proved to be so popular that an entire sub-genre is named for it. Ruritanian adventure, named for the fictional nation, is defined as “of, relating to, or having the characteristics of an imaginary place of high romance.”

To readers of Victorian literature, it wonderful to read actual names. What do I mean? Well, Victorian novels that purported to be about actual people and places would often do this:

“He was the Count d’A—— from the estate of G—— in the county R——– which is just to the north of S——.”

“Really, Mr. T——–, must you speak in dashes? You sound like that common M—— from E——–.”

I know they were trying to defend themselves from a libel suit but give me a break! Either make up something entirely, as Hope did, or pick out an older, extinct name and use that. We, the readers, promise to forgive you. What bugs me most, though, is when the writer makes up a name or city and then uses the dashes anyway! I think they were trying to give the illusion of breathless gossip.

Yes, I realize I am upbraiding authors who have been dead for a century. I am sorry. One tires of dashes.

I take comfort in the fact that Thackery had a rather funny dash bit when he went off on a tangent in Vanity Fair.

Silent movie connection:

The Prisoner of Zenda was a popular best-seller and was adapted three times for the silent screen. The 1913 version survives in archives. The survival status of the 1915 version is unknown. However, it is the 1922 version that is the most famous of the silent era. Starring Lewis Stone and Alice Terry and directed by Rex Ingram, it is a lush adventure. The film also contained a star-making performance with a very, very young Ramon Novarro walking off with the picture as the theatrical villain Rupert of Hentzau. (You can read my review here and I also cover the 1937 film.)

It should be noted, though, that the definitive film version of this book (in my opinion anyway) is the 1937 Selznick production starring Ronald Colman as Rudolf/The King and Douglas Fairbanks Jr. as Rupert.

And the worst version? That would have to be the 1979 Peter Sellers version, which attempts to turn the story into a knockabout comedy. In the end, the critics took glee in giving this film a knockabout in their reviews. Well, it is pretty dreadful.

How about another remake? Real, honest-to-goodness fencing has been missing from motion pictures for far too long. Enough of the cheesy CGI-enhanced acrobatics! I want sabers and banter and shadows and the thwacking of candles and ropes! The Prisoner of Zenda has all this and more.

In the meantime, enjoy the novel.

☙❦❧

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

Disclosure: Some links included in this post may be affiliate links to products sold by Amazon and as an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

Oh I am very fond of both the Hope novels and have nice popular editions pre-1910. I pull them off the shelf every few years and re-read them. I agree, a good version of both novels would be a welcome entertainment. No real need for CGI, either. Now to fantasize about who could be cast? The 1937 film is hard to beat, how I wish Selznick had gone through and shot the sequel.

Same here! It really is a lost opportunity.

On the subject of ‘The Prisoner of Zenda’! I am a great aficionado of Ruritanian genre films, books and plays. The silent version (and I am devoted to silent film….but…) didn’t quite do it for me, although the book was very good. The talkie (with Doug Fairbanks, Jr.) I thought really wonderful. The silent version….I wished to see more of Barbara LaMarr! If you compare Elinor Glyn and George Barr McCutcheon with Anthony Hope, I think Madame Glyn hits it for the infusion of romance, but Hope does better with intrigue.

Michael Viktor Butler.

I go into more detail in my movie review but I think the essential problem with the 1922 version is that Rex Ingram has no sense of humor (a BANANA PEEL GAG for heaven’s sake) and that Ramon Novarro and Barbara La Marr are more interesting than Lewis Stone and Alice Terry but receive a fraction of the screentime. It’s no coincidence that Scaramouche, which features Novarro as the hero, Stone as the villain, is the much stronger Ingram swashbuckler.

Oh, I love the Zenda novels – and the 1937 adaptation! I must say that I find the 1952 Stewart Granger thing also rather appalling… I know the BBC made a serialised version in 1984, and I’d love to take a peek at it – but have had no luck so far.

Amazon is streaming it here in the USA (not sure about the European situation) but I was extremely amused by the cast. As a fan of British mystery shows, it was most amusing to see Miss Lemon from Poirot and Freddy Fisher from Pie in the Sky in major Ruritanian roles.

Alas, it won’t show this side of the Pond…