Menahem Mendl, a Jewish man living in pre-Revolution Russia,has a large family and not much money but he does have an abundance of ideasfor get rich quick schemes. From selling corsets to insurance to brides, Mendl’splans are ambitious but never quite turn out the way he intends.

Head in the Clouds

As far as film hooks are concerned, Jewish Luck has a great one: Filmed around the same time as Battleship Potemkin with the same cinematographer, Eduard Tisse, Jewish Luck features an elaborate dream sequence using much of the same Odessa scenery, including the famous steps.

And then there is more to it. Much, much more. From the impeccable pedigree of its story to the importance of its leading man to its earthy approach to the shtetl life, Jewish Luck is a film that rewards careful viewing.

Quick note on the spelling of the protagonist’s given name: Obviously, the alternative romanization of proper names has plagued more languages than Yiddish and the “kh” sound—that guttural that is unknown in English but so common everywhere else in the world—has no single letter equivalent. I am using the spelling “Menahem” because I think it will produce a better pronunciation in English speakers than “Menakhem” or “Menachem” but this is clearly my opinion. In all cases, “h” “kh” or “ch” are pronounced like one is choking on a bone. That semester of German you took in high school should prove useful.

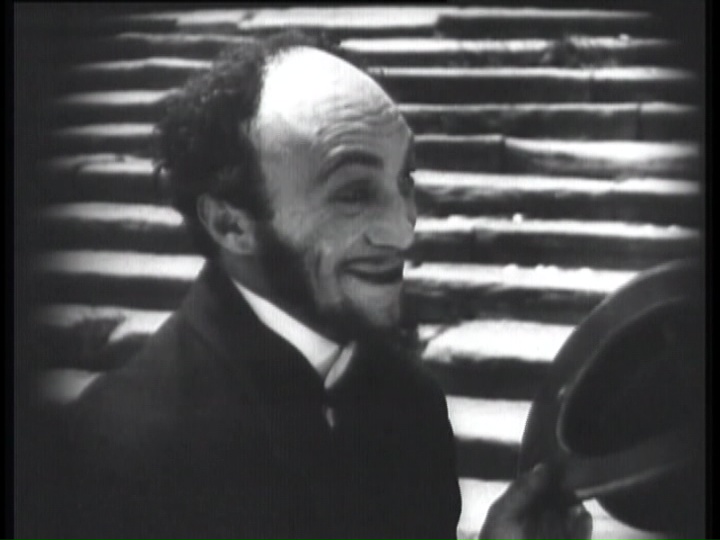

Jewish Luck follows the adventures of Mendl (Solomon Mikhoels) as he tries to make some money in Russia just before the Revolution. There’s no real plot to the picture unless you count the attempts of the equally poor Zalman (Moisei Goldblat) to court the wealthy Belya (Tamara Adelgeym).

Mendl and Zalman head to Odessa in the hope of striking it rich with insurance and/or ladies undergarments but they are harassed by the local constabulary and lose both money and goods bribing their way out of an arrest. Mendl stumbles across the prospects book of a matchmaker and decides to try his hand at what could be a viable profession.

In the film’s most famous scene, Mendl imagines himself as a smooth and genteel matchmaker called upon to “save America” due to the shortage of brides. Mendl leads willing ladies up those Odessa steps and off to waiting freighters where they are divided into “wholesale” and “special order” and shipped off to those lonely American bachelors.

Real life is more complicated, of course, and while I will not reveal all, I will say that Mendl really should have met both parties before contracting the marriage.

Will Mendl finally make his fortune? Or will he remain a luftmentsh with his head perpetually in the clouds? See Jewish Luck to find out!

While the film is generally a light affair, it is pretty frank about the police shakedowns and other unpleasantness that could happen on the streets of Odessa. (Odessa had been the site of tsar-sponsored bloody antisemitic pogroms within recent memory of Soviet audiences of 1925.) The picture takes great pains to establish that the events take place under previous management with a portrait of Nicholas II being shown in closeup twice in the same scene. This goes along with the attempts by the new Soviet government to bring Jewish citizens into the fold and we will be discussing that particular aspect of the regime later in the review.

Director Alexander Granovsky and cinematographer Eduard Tisse create a warm, natural world for the characters of Jewish Luck to inhabit. A bit shabby but definitely homey and the real locations add considerably to the films overall effectiveness.

The performances are a bit exaggerated, though, I understand, not nearly as over-the-top as what was found in theaters at the time. Solomon Mikhoels, who plays Mendl, is a mischievous delight as all his hard work and plans go awry but he tries, tries again. Getting ahead is his dream but every deck is stacked against him and he is too nice to be a proper schemer.

Mikhoels has an absolutely wonderful walk as Mendl. Head and shoulders back, umbrella tucked under the arm, fast steps. Away we go! There’s a cockiness to him, a serene confidence that all will turn out as he hopes, contrary evidence be damned. That is some fine physical acting right there.

As a popular and acclaimed actor, particularly on the stage, Mikhoels was appointed chair of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC). The committee was formed in order to build support for the Soviets in the wake of Germany’s invasion of the USSR but Mikhoels’ contact with western governments, as well as his status as a popular Jewish actor, made him a target for liquidation once his liaison work was no longer required post-WWII. (How dare he literally do the job he was ordered to do in the first place?)

Joseph Stalin ordered Mikhoels’ murder in 1948 but the assassination was made to look like a traffic accident and he was officially mourned. The Night of the Murdered Poets in 1952 involved the execution of thirteen Jewish men, who had been in state custody for years and tortured into confessions of conspiracies against the state. They had been fellow members of JAC and the official turn to state-sponsored antisemitism in the Soviet Union was complete.

(Per The Encyclopedia of Russian Jewry, Moisei Goldblat, who plays Zalman, passed away in Haifa, Israel near the age of eighty, which is a small bit of good news in this very tragic story. Any death that doesn’t involve arrest, torture or murder is a win with this particular chapter of Jewish history. Also, Alexander Granovsky escaped to Weimar Germany and died in France, so that’s another reasonably torture-free ending.)

It’s also worth noting that these events roughly coincided with the Hollywood blacklist and the heyday of McCarthyism, which disproportionately targeted Jewish artists. The purpose of bringing this up is not whataboutism but a reminder of how widespread antisemitism was and how Jewish people were targeted for being bad communists, good communists or non-communists caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Jewish Luck was based on The Adventures of Menahem Mendl, a novel by esteemed Yiddish author Sholem Aleichem (pen name of Solomon Rabinovich). Aleichem is probably best remembered by the general public for writing Tevye and His Daughters, which was adapted as Fiddler on the Roof.

The Adventures of Menahem Mendl is a bit more obscure—only one translation into English was ever published, from what I can tell—but quite delightful in its own right. It consists of letters between Menahem Mendl, who is off in Odessa trying to make money as a speculator, and his wife, Sheineh Sheindl, who is exasperated by her husband’s naivete and general lack of common sense or business sense.

All of the letters follow a pattern: Firstly, the formal greeting. And secondly, a quick launch into more casual language and a flood of information. The reader is swept along in the conversation between spouses and, like Sheineh, we know that Mendl is cruising for a bruising but we can’t do a thing about it.

If I have one complaint about Jewish Luck it is the removal of Sheineh Sheindl from the story. Her letters make up half of Aleichem’s novel and the affectionate insults she lobs at her wayward husband provide at least half of the belly laughs. Further, she is essentially an audience surrogate as we are shouting “Don’t do it! Don’t do it!” to Mendl along with her. Cutting her from the film is like making a Sherlock Holmes film without Watson and we all know how those turn out.

Adapting the novel as a more traditionally structured film was a strange decision to begin with because silent cinema was the ideal vehicle for sharing the flavor of the original. Audiences would not mind excerpts of the letters being shown and they could have enjoyed Mendl’s pie in the sky dreams, as written down for posterity, coming face to face with reality.

(I heartily recommend the novel. If you are reading it in English, translator Tamara Kahana does an excellent job of balancing the patois of the characters with the need for readability and her introduction clears up any confusions about some of the unusual slang or contemporary references the characters make.)

Following the popular trend of hiring a bestselling writer to pen the title cards, the Russian intertitles were written by Isaac Babel, a devotee of Aleichem’s work. (Babel also wrote the screenplay for Benya Krik, a film about Jewish gangsters in Odessa, and adapted another Aleichem work for Wandering Stars, now a lost movie.) Babel was at odds with Joseph Stalin’s new edicts regarding the arts and was arrested in 1939, tortured into a confession of treason and shot in 1940. His papers were seized during his arrest but were never recovered and are presumed to have been destroyed. Babel was rehabilitated posthumously soon after the death of Stalin.

I possess too little knowledge of both Russian and Yiddish to judge the quality of Babel’s title cards or to tell you whether or not they captured the essence of the Aleichem original. (Do let me know if you have any insights.) In my experience, celebrity title cards have been hit or miss but, of course, I have mostly seen them in mainstream American productions. I suspect Babel’s work was pretty darn good.

All of the other Jewish-themed films I have reviewed, whether made in Austria, Germany or America, have all dealt with the question of separation vs. distinction to some degree. Jewish Luck is no exception and it was made during a time when assimilation was not only a debate among Jewish people but actual state policy.

Life had always been precarious for Jewish people living in Russia but the brutal anti-Semitic policies of Tsar Alexander III and his son Tsar Nicholas II had forced many to flee west. Others stayed and embraced revolutionary ideals. This led to a wholesale campaign for assimilation after the Revolution spearheaded by Jewish communists. In Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds, J. Hoberman writes that for some Jewish party members “Bolshevik antagonism toward religion, the bourgeoisie, and Zionism seemed and unavoidable price to pay for the end of state anti-Semitism. New secular Jewish institutions supplanted rabbinical courts, weakening traditional authority and helping bind Jews to the revolutionary regime.”

The Yevsektsiya, the Jewish arm of the Russian Communist Party, initiated and implemented the closing of synagogues, yeshivot, Hebrew schools and most traditional aspects of Jewish life. Under Stalin, the Yevsektsii were liquidated beginning in 1934 and were completely purged from the government by the late 1940s.

In the shadow of this, the Russian Yiddish stage flourished in the 1920s. Alexander Granovsky was the impresario and Marc Chagall’s exuberant designs created an exciting new beginning for the Moscow State Yiddish Theater (GOSET). GOSET put on a three-play production called the Sholem Aleichem Evening in 1921 and that would form the basis for Jewish Luck.

GOSET was wildly popular with general audiences, a full two-thirds of the audience for 200,000 required synopses in Russian in order to follow the action, but was a subject of contention among Russian Jews due to its embrace of the Yevsektsiya philosophy of no religion, heavy modernism and an emphatic rejection of shtetl culture. Still, it was a haven of Jewishness in a sea of secularization.

So, with all this context, 1925 Russian viewers of Jewish Luck would have understood the film’s message to be that the hardships of shtetl life were the fault of the tsars and that such a life would no longer be necessary under the new regime. There are no overt cries for assimilation but shtetlekh are very much treated as past tense. (We’re way past tents, we’re living in bungalows.) It should be noted that The Ancient Law, made two years earlier, was praised for avoiding the trope of a shtetl being portrayed as dirty and unkempt.

While Jewish Luck is not without its charms and historical interest, the loss of Sheineh Sheindl’s voice is a blow from which it never really recovers. This is definitely a case where you will benefit from reading the book after seeing the film. However, Solomon Mikhoels is hard to resist in the leading role and the film’s natural settings and cultural trappings make it a must-see for anyone interested in Soviet history, Jewish cinema or just good filmmaking.