Gale Henry plays a detective hot on the tail of some thieves who have swiped a secret formula. What ensues is best described as a sort of silent movie Donkey Kong with trapdoors, secret doors and a big tub of water.

Game Over

I’ll get something important out of the way: there is no direct evidence that Gale Henry inspired Olive Oyl, Popeye the Sailor’s gawky girlfriend. But, I mean, look at her! I cannot believe that Olive was created independently of Gale, especially considering the latter’s popularity.

Dubbed “the Elongated Comedienne,” Henry is probably best known for her supporting roles in some classic Hal Roach comedies but her solo work is what we will be looking at today. Not much of it survives but we are fortunate enough to have The Detectress, which is fascinating for its portrayal of gender roles and its oddly video game-like structure. The not-so-good part is that the short is rather heavy on Chinese stereotypes. (Yes, they were offended at the time. Yes, they wrote letters. Not just Chinese people but Japanese, Italian, African-American, Irish… The mythical la-la land in which minorities met stereotypes with joy, delight or just silence never existed.) We’re going to adding context to those stereotypes along the way and see how they developed.

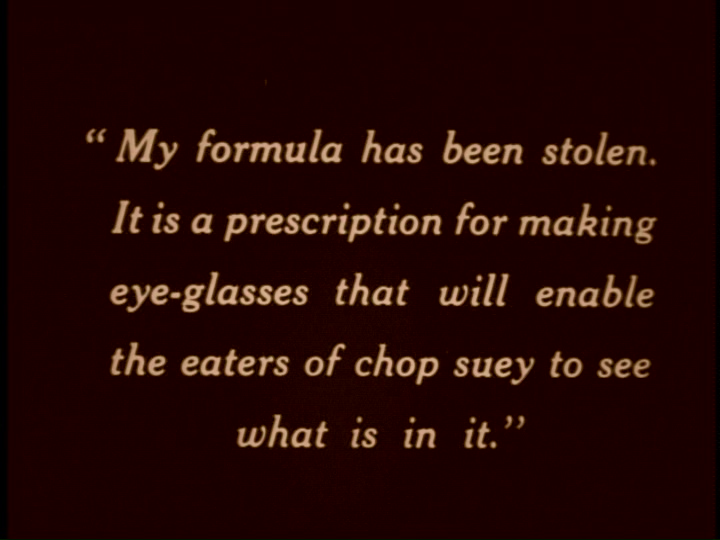

The plot of The Detectress kicks off when Chinese criminals named (sigh) One Lung (Hap Ward) and Jip Yu (Eddie Baker) attempt to steal a secret formula for glasses that will enable restaurant goers to see what is in the chop suey they order. Gale Henry plays a detective who, unbeknownst to her, has the formula in her own pocket, sets out to recover the stolen paper.

Henry is kind of assisted by a uniformed policeman (Milburn Morante), who can barely be roused from his nap. That’s okay, our Gale isn’t afraid to get her hands dirty.

What follows is a madcap chase through the criminal gang’s hideout including trapdoors, ladders, water, secret passages and disguises. (Spoiler) But then the whole thing turns out the be the drug-induced imaginings of Henry, who accidentally inhaled opium while looking for the formula. The innocent days of silent film, folks!

Gale Henry is great fun as the heroine, who isn’t very bright but has plenty of heart and guts. And, fortunately for her, none of the other characters are exactly ready to split the atom. (I have to admit a weakness for the “everyone is stupid” school of comedy.) Henry’s rubber limbs, zany walk and enthusiastic slapstick all add up to some solid humor.

Films of the silent era were reasonably open to the idea of women in law enforcement. Two films that I can name without spoiling their plots are The Penalty with Ethel Grey Terry as a government agent and The Boob, which featured Joan Crawford as a Secret Service investigator. However, Henry’s detectress is easily one of the more independent of the lot. As Steve Massa puts it in his essay on Henry: “It would be productive to investigate whether, under the guise of comedy, Henry had, in fact, greater freedom of movement than the popular lady detectives and cliff-hanger heroines whose films she spoofed and played on.”

I certainly think that Henry was afforded several advantages. First, her gawky appearance made her less likely to be portrayed as an object of lust to silent film villains, a common suspense trope even in knockabout comedy. Heck, even Olive Oyl had to deal with it but the trope is not used here, thank goodness. Second, the surreal nature of the film meant that she could bend gender rules to the breaking point without any pearls being clutched. Silent era heroines in general tended to be a more vigorous lot than their talkie counterparts but Henry’s character is a dynamo even by those standards. She is essentially allowed to behave exactly as a male comedian would in a similar role. That was a rare thing then and it’s a rare thing now.

Morante’s policeman is Henry’s opposite number with a cartoonishly large uniform and an unfailing capacity for letting the bad guys get away. (Like fellow funnyman Al St. John, Morante spent most of his talkie career as a character actor in westerns.)

And now we are going to address the elephant in the room: Chinese immigrants and chop suey. Much to the horror of Chinese-Americans, Chinatown was consistently portrayed in movies as a den of sin and vice populated almost exclusively by prostitutes, opium addicts and hatchet men. (And, usually, one impossibly pure young lady played by a white actress and given to kissing birds.) The Chinese were the first immigrant group to be specifically targeted for a ban and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 severely curtailed the types of Chinese workers allowed to enter the United States.

However, in 1915, the law was changed and inadvertently added a loophole that was big enough to drive a Model T through: Restaurants.

Chinese people could leave the U.S.A. and return if their purpose was to bring in workers (in other words, their families back in China) for their restaurants. The restaurants had to be “high grade” fancy places but that was doable if several investors pooled their resources to set up a “chop suey palace” or similar establishment. Because the law wasn’t already racist enough, Chinese owners also had to be vouched for on their visas by two white witnesses but a solution was quickly arranged. Supply vendors would happily swap their signatures in exchange for a delivery contract.

In any case, Chinese restaurants had been going concerns for decades because they were often inexpensive, offered generous portions, kept late hours, were open on holidays and were especially appealing to the other major non-Christian immigrant group in America at the time: Jewish people. With a built-in market of bohemians and Jewish immigrants sewn up, Chinese restaurants entered the mainstream.

Of course, when we talk about Chinese food, we are talking about the food these restaurants served that was tweaked to take into account local ingredients and the palates of customers who were not of Chinese descent. And that means we are talking about chop suey.

The origins of the dish are mysterious even if the ingredients are a reliably tasty combination of meat and vegetables. (No special spectacles required.) Long thought to be invented in America, food historians are starting to embrace the theory that chop suey evolved from a genuine Chinese dish with a name that literally means “miscellaneous leftovers.” A long and proud tradition of cooks the world over: stews, hashes, soups and casseroles designed to use up a bit of this and a bit of that.

The Detectress was made during the Chinese restaurant boom (the number of establishments had doubled in just a few years) and chop suey was well on its way to universal acceptance around the country. I have seen some early descriptions talk about offal like tripe and liver, as well as vegetables that might not have been familiar to the average white American of the time. Things like bean sprouts and bamboo shoots. Xenophobia was battling rumbling bellies, in short, and The Detectress is a reflection of that conflict. (One is reminded of the droll recurring Catherine Tate sketch in which a chauvinist couple is horrified at being offered tempura, which they deem “battered veg and spicy jam” and gazpacho, which they claim is “cold tomato soup with tiny bits of stale bread.”)

And, of course, we must remember that the “we don’t know what is in that food” paranoia has led to all sorts of mad myths about Chinese restaurants, up to and including “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.” Considering that riots and lynchings aimed at Chinese immigrants had been occurring for decades, it’s easy to see why such rumors would essentially be leaving fuel beside a box of matches.

And so that is the context for The Detectress. I hoped you enjoyed this little detour into immigration law and food history but back to the film itself.

One of the weirdest things about this picture is that it feels strangely familiar to anyone who has played enough Mario Brothers or some other sidescrolling video game. The idea of climbing up a ladder and trying to defeat villains while avoiding falling through a trap door is very old school gaming. Add the cyclic nature of the acting (fight, fall, splash, climb, fight) and you basically have Donkey Kong as a silent film. Gale Henry may not have lasted as a producer but it’s a shame she passed away before the video game revolution. I would play anything she designed.

All in all, this is a film that is worth seeing if only for a chance to watch Gale Henry do her stuff as a solo comedy star. It’s unfortunate that so much of her work is lost because she’s a dynamo and a real pleasure to watch.

The Detectress has some rather unfortunate stereotypes but it is also has some excellent gags and is a showcase for Gale Henry in her prime.

Where can I see it?

Released on DVD as part of the Slapstick Encyclopedia. Some of the online versions I have seen cut out random title cards for heaven knows what reason.

***

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

I couldn’t help it. I snickered at the villain’s names. I found them “punny.”

Embarrassment aside, I will check this out. You make this sound like a fun little trip which should go well with popcorn and some wine.

It’s definitely worth seeing, especially for fans of slapstick.

Thanks for another informative review. When I first watched it, I couldn’t help but feel like I was watching a cartoon/video game.

I also started to wonder if Minnie Pearl’s look was influence by Gail Henry. My dad was a big Hee-Haw fan.

Yes, Henry really went all in for the cartoonish, pixelated effect. I like it and am very curious to know if her other films were this way or if this is an outlier.

Minnie might have also been inspired by ZaSu Pitts, perhaps?

Love the Olive Oyl connection. And I think you were a food writer in a previous life. . . hell, you’re a food writer in THIS life! Your output on food is on par with your film work and could easily justify a spinoff blog! I’m hungry for Chinese . . .

Thank you so much! I had fun researching this one, especially since I have a chop suey post in the pipeline. 😀

very interesting review!

Thank you!

Speaking of silents featuring women in law enforcement, another example is the one in which the female government agent goes undercover to bust a ring of bootleggers in the Tennessee hills. She poses as a visting artist, a painter of landscapes. (I can’t remember the title, but TCM showed it recently, I think as part of Kino’s “Pioneers” collection.). Anyway the opening setup similar to that in “The Penalty,” with the desk-bound boss hesitantly discussing a particularly dangerous case, and the courageous female agent then insisting on the assignment.

Yes, it was pretty darn common and there is at least one title I didn’t name because the lady’s status as a detective is a big reveal in the finale.

Re: games and films – have you seen Cuphead? It’s designed to look like a 1930s animation and it is BEAUTIFUL. Even the soundtrack is heavily influenced by 1920s/30s jazz.

No, not yet.