A group of conspirators plan to rob a bank. (I am told that their plan is bold.) They succeed but can they escape the long arm of the law? Sleazy entertainment from the pioneering Lubin studio.

Breaking the bank

By 1904, the making of films had become mired in piracy, counter-piracy, lawsuits, absurd patent claims and the muddiest copyright waters imaginable. Thomas Edison’s film company was famously the instigator of many of these issues but another big player is less famous today, Siegmund Lubin of the Lubin Manufacturing Company. Lubin made and sold his own film projecting equipment and duped films made by Edison and others. Edison responded by duping Lubin’s films and it all got rather messy.

Around this time, the major movie players recognized that there was a demand for fiction films and they rushed to meet that demand. Movies of mid-1900s were split between fiction films and actualities—footage of exotic locales, animals, political events, etc. While the actualities could claim educational value, the fiction films often portrayed (in title if not in action) distressing amounts of crime, madness, murder and general sleaze, especially by the more socially conservative standards of the era. Take this random sample of titles available in a trade magazine: Trial Marriages, Flirting on the Sands, Artist’s Model, Hooligans of Far West, The Murderer, Female Highwayman, Foul Play, The Automobile Thieves and Dr. Dippy’s Sanitarium.

As they do today, concerned citizens expressed dismay that these films might spoil young minds and bring up a generation of flirts, thieves and ne’er-do-wells. Entrepreneurs hoping to make a living screening films had to work hard to fight this negative reputation and would employ religious and educational pictures to attract families.

The Bold Bank Robbery would likely not have made it onto the program of one of those picture shows. Crime was what the audiences wanted and crime was what they would get.

The picture opens with the bank robbers in evening dress planning their heist and then we are shown the various steps they take to break into the bank, blow the safe door and escape with the money. However, the police quickly track them down and after a chase, the robbers are captured and sentenced to prison. All of this in about six minutes.

Also, please note that the light is painted directly onto the scenery.

It’s not exactly the most sophisticated production with real street scenes clashing with the obvious painted sets that look more suitable for Sesame Street than a crime picture. (The vault is carefully labeled “vault” for example.)

However, this film is an excellent example of the “emblematic shot” described in The Encyclopedia of Early Cinema as “a closer view of a principal (sometimes still a full-figure shot, sometimes a waist-up shot or bust shot) or significant object at the beginning and/or end of the film functions as a kind of punctuation point.” The most famous example is the shot of an outlaw firing his gun into the camera in The Great Train Robbery but the technique was used fairly often in films of the 1900s. (Lubin would release his own unauthorized remake of The Great Train Robbery in 1904.)

In the case of The Bold Bank Robbery, the filmmakers go for dramatic contrast by using the emblematic shot at both the beginning and end of the film. At the beginning, we see the laughing bank robbers smoking cigars in full evening dress as they plan their heist. At the end, we see the men in prison stripes as they serve their time for their crimes.

Showing that crime does not pay not only provided an ending for the picture, it also shielded its makers from charges that their picture was making crime look glamorous, accusations that would continue to dog the entertainment industry through the gangster film craze of the 1920s and 1930s and into the present day.

Lubin viewed his films as a means to an end: selling his projection equipment. An rather cheeky ad from 1904 (yes, I know it says 1905 but it was published in autumn of 1904) shows that The Bold Bank Robbery was sold alongside Lubin’s The Great Train Robbery ripoff and that with the projection outfit, you could get a free Victor talking machine with horn and soundbox to play along with the movies. (The smaller crowds in early motion picture audiences would have lessened the Achilles heel of movie sound during that period: amplification.)

The Bold Bank Robbery could be purchased for $66 (about $1800 in modern money) while the projection kit was $99 total. (In those days, 40 to 100 copies of a film sold would be about average, 200 copies would be a monster hit and 400 would be a #1 blockbuster.)

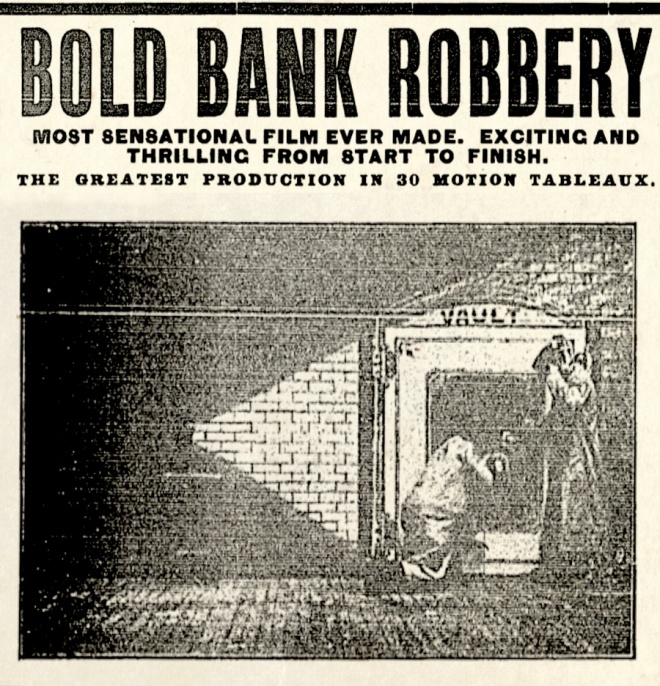

An ad from 1905 shows that Lubin was still going for the crime-loving crowd:

Like so many of his contemporaries, Lubin had trouble adjusting to the transition to talkies and was out of the motion picture business by the mid-1910s. However, one interesting footnote in his career is that he saved part of what would become Paramount in its infancy. The Squaw Man was the do-or-die debut of Jesse Lasky’s eponymous company but the inexperienced technicians had inadvertently punched sprocket holes at incorrect intervals. The film was unplayable! As a favor, Lubin took the film, glued on some new strips of sprocket holes and saved the picture and the company.

The Bold Bank Robbery is no masterpiece of early cinema but it does show what the average American moviegoer was demanding to see: violent crime, exciting chases and a tidy moral lesson at the end. It’s also a rare chance to see a Lubin production from the height of the movie patent wars. More valuable historically than as entertainment.

Where can I see it?

The Bold Bank Robbery is found as a secret extra in The Movies Begin box set from Kino Lorber. On the film selection screen, keep going right and a hidden arrow will take you to a It Came from Beneath the Vault screen with ten films listed (The Bold Bank Robbery is found on the second menu screen in this area, the arrow was hidden for me but just go right and you should find it). The films are mostly from the Library of Congress’s paper print collection and are presented without scores.

***

Like what you’re reading? Please consider sponsoring me on Patreon. All patrons will get early previews of upcoming features, exclusive polls and other goodies.

I’m pleased that things moved on from “Motion Tableaux.” I believe the history you have related is of more interest than the film, to me. Not the only equipment manufacturer to make the ‘software’ mainly to sell the projectors and cameras, of course.

Yes, the film itself isn’t much in itself but it’s invaluable from a historical perspective. I wish more Lubin, Vitagraph and pre-Griffith Biograph were available to create a more rounded view of this interesting period. (Melies, Gaumont and Edison have all received excellent box sets.)

Ha! I might never have noticed that “secret extra!” Thank you.

Yeah, it was new for me too. Glad to help!