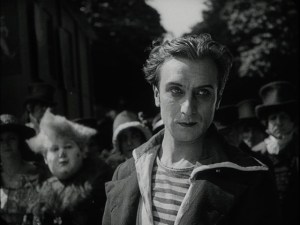

Ivan Mosjoukine takes the title role in this biopic of legendary English Shakespearean actor Edmund Kean, whose brilliance on the stage was undercut by his eccentric and self-destructive personal life. Yet another example of the astonishing films being made by the Russian emigres who fled their country’s political turmoil for the relative safety of Paris.

This review is part of the Backstage Blogathon, hosted by Sister Celluloid and me. Be sure to read the other great posts!

Love Hurts

It is a truth universally acknowledged that actors love to play other actors. This tradition has long existed on stage and easily transferred over to the screen. It’s no surprise that the life of Edmund Kean (1789-1833) would be a tempting topic for a film. A brilliant Shakespearean whose talents were eclipsed by his own inner demons and some nasty scandals, Kean is precisely the sort of role actors fight to play.

The story of Edmund Kean was particularly suited to the brilliant artists at Albatros, a French movie studio run by Russians who had fled the revolution in their own country; it had taken Europe by storm with its wildly brilliant films. The Russians were noted for their ability to blend extreme artistry with crowd-pleasing blockbusters and their impressive talent for handling epic subjects with humanity and sensitivity. Ivan Mosjoukine was their biggest star and his flair for the eccentric meant that his career was delightfully unpredictable. It seemed right that the biggest star of the Russian emigres would play the greatest star of the English stage.

Before we get started, there are a few things to keep in mind. First of all, European films of the silent era did tend to play things in a broader, more stylized manner than American films of the same period. (This is a massive generalization, I know, but I beg your indulgence.) The makeup and performances will be on the intense side. This is by design (the Russians were perfectly capable of playing subtly) and should be appreciated on these terms.

Second, as a film, Kean does its audience the courtesy of assuming that they can follow the story without every action and old-fashioned institution being explained to them. In theory, this should make Kean very challenging for modern viewers. However, given the enormous Jane Austen revival in the films and television of the past two decades, I dare say that a good number of viewers will be quite comfortable interpreting the customs, manners and eccentricities of Regency England, perhaps more so than 1920s viewers. We may not be experts on the behavior of Shakespeareans in the early nineteenth century but, darn it, we recorded most of Pride and Prejudice off A&E and that’s plenty good.

Are we ready for some juicy Regency scandal with a Franco-Russian twist? I thought so!

The film opens on a play within a play, which sets the mood for the stylization that will follow and also borrows a trick from Shakespeare, whose works will figure prominently into the plot.

All of London society is talking about the dashing Edmund Kean (Ivan Mosjoukine), the greatest Shakespearean actor to come along in ages. We are told that he has certain eccentricities but who cares about those when Kean’s Romeo is wringing tears and gasps from an appreciative audience? His fame is so great that even the Prince Regent (Otto Detlefsen) is intrigued and decides to attend a performance. Also in the audience is the Danish Ambassador, Count Koefeld (Georges Deneubourg), his charming Venetian wife, Elena (Nathalie Lissenko), and a wealthy young heiress named Anna Damby (Mary Odette).

When Kean enters the scene, both Anna and Elena are immediately smitten. Kean takes no notice of little Anna but immediately hones in on Elena. During the famous balcony scene, he repurposes the play’s dialogue to flirt with her.

The Prince Regent is himself in love with Elena (a flirtation tolerated and encouraged by her husband and society at large) and he considers Kean to be something of a royal pet. Kean is free to look and to admire but it is to be understood that Elena’s first obligations are to the Regent.

Okay, we’ve seen Kean’s performance but what of this eccentricity we were promised? It’s coming! Kean’s only real friend, Salomon (Nicolas Koline), is the prompter of the Drury Lane theater, as well as a nursemaid to the famous actor and he has his work cut out for him. The morning after his triumphant performance as Romeo, we are shown Kean stuffing poor Salomon into a fencing mask and demanding a quick match over the breakfast table. He then dresses Salomon as a tiger to scare away his creditors and both men make their escape disguised as a sailor (Kean) and his wife (Salomon). So, yeah, pretty eccentric.

What follows is a little more flirting between Kean and Elena and then off for a good carouse. Kean’s alcohol-fueled dance frenzy is the most famous scene in the film thanks to its clever and rapid editing. (This is a year before Battleship Potemkin, a film often erroneously credited with “inventing” things cut really fast. Ha! Take that, Soviets!) Kean’s sailor disguise was clearly not chosen by accident as he goes to a maritime hangout and dances the night away with seafaring folk from around the world, downing enormous amounts of spirits in the process.

I must say, though, that Mosjoukine and Volkoff did sometimes overplay their hand when it came to symbolism. During Kean’s nautical carouse, we switch scenes to Anna’s bedroom, where she remembers Kean’s Romeo drinking poison. Volkoff then cuts to Kean chugging liquor because it’s poison to him, get it?

However, most of the scene is excellent. Kean’s carousing is without pleasure, there is something manic and compulsive about it, the joy seems forced and fake. Edmund Kean is neither satisfied nor happy and he parties to fill a void in his life. We soon learn that he was once a humble travelling player and that he still is friends with performers from his old life. Was his step up in rank really a good thing?

The rest of the film concerns Kean’s growing infatuation with Elena, his reckless partying and his eventual downfall, a fall from grace that also ensnares Elena and poor little Anna. The poor young thing has a terrible crush on Kean, you see, but is battling an arranged marriage. (Arranged marriages are never a good thing in movies unless the two parties meet first without recognizing each other. It’s a most peculiar thing.) The male party in this arranged marriage Lord Mewill, played by Kenelm Foss, who (along with Mosjoukine and Volkoff) adapted the script for Kean.

So, we have moved beyond love triangles and are now using love octagons in this picture. Can Kean navigate these intrigues and still keep his place in society? Or will he commit a fatal misstep and see his world come crashing down? Well, if you know about the real Edmund Kean, you know that he’s riding for a fall.

A particularly angry review on IMDB complains that this film fails because (prepare yourself for a shock) it changes the real events in the life of Edmund Kean. A biopic taking liberties with the historical record? Has such a thing ever happened? (Faints on brocade couch only to be revived with smelling salts.) Look, I get annoyed as anyone about the ridiculous myths spread about, say, Mabel Normand in Chaplin but Kean does generally get the tale of Edmund Kean right. Characters are combined and incidents are telescoped but it does present him as a very talented actor whose carousing and indiscretion do him in, which is the basic thumbnail sketch of his life and career.

(In any case, the film was based on a play by Alexandre Dumas père and while the film makes many changes–mostly by killing off much of the cast– many of the “inaccuracies” of Kean are the inventions of Dumas and not Foss, Mosjoukine and Volkoff. You can read an English translation of the play here.)

The real Edmund Kean was short, he specialized in playing Shakespearean villains, not heroes (his Romeo has been described as “almost laughably unpersuasive”) and his on-stage collapse was as he played Othello opposite his son. Further, he was woefully unfunny while Ivan Mosjoukine usually injected at least some humor into his roles. Obviously, changes were made but the same is true with most films based on real events. Kean deserves credit, though, for not falling into the common trap of biopics.

What trap is this? The fade-out-two-years-pass thing. You know, films that don’t have a really strong narrative thread but want to show as much as their subject’s life as possible. As a result, far too many biopics start with a dramatic scene from the subject’s childhood, fade to them as adults and then skip along until the end. It’s a very jerky style of scriptwriting and one of the main reasons I really don’t care for biopics in general. Seriously, choose any random biopic and you will see this nonsense.

Kean takes the Lawrence of Arabia approach: show the most interesting couple of years in the subject’s life and wring everything you can out of them. We don’t need to see how Kean or Lawrence got to their starting position in the film, we don’t need sepia-toned scenes of childhood or agonizing detail on the origin of each and every character quirk. Good acting and smart scripts tell us what we need to know.

Kean is presented as a play within a play and the performances of the talented cast (mostly Russians in the key roles) reflect this layered approach. Kean as Romeo romances Juliet on the stage and carries on a confident (albeit subterranean) seduction of the countess in her theater box while the real Edmund Kean cringes with uncertainty about her returning his affections. Salomon is Kean’s drinking buddy and servant in the eyes of the world, his closest friend and confidant in private and only Salomon himself knows that he is father, mother and nursemaid to the sensitive actor.

Edmund Kean’s mistake, of course, is that he mixed up his layers. He wears the mask of a jealous lover when a loyal subject is called for. Hypocrisy is the order of the day among the gentry and it must be tolerated if the hypocrite’s title is high enough and who is higher than the prince regent? A student of humanity but always separated from it because he seems to be filtering all his interactions through the works of Shakespeare, Kean cannot understand this. He realizes too late that his life is not a comedy but a tragedy. (Students of Shakespeare will enjoy hunting down all the Easter eggs in the film related to the Bard’s writings, particularly Hamlet.)

Kean doesn’t fit in with the noblesse and does not really understand the upper-crust culture with which he surrounds himself. His best friend is the very common Salomon and he chooses to party with fellow actors, sailors and travelling players. When things go south with the gentry, he reacts like a travelling player (that is, a normal human being with emotions) and that results in his downfall. His talent has raised him on high but proves to be a curse because it separates him from the culture he understands. No doubt, Mosjoukine the refugee (no matter how successful) could understand these feelings.

Now I’ll let you in on a little secret about Ivan Mosjoukine: his fans watch his films waiting for his inevitable emotional implosion. No one could break down like Mosjoukine, no one in Hollywood and no one in Europe. His acting is always most powerful when his characters are at their weakest point and Kean is no exception. After collapsing on the stage, we see that Kean is a broken man. His rash actions have irrevocably separated from the woman he loves, estranged him from his formerly adoring audience and made him an easy target for debt collectors and other enemies. He is hollow, the spark of madness that made him irresistible has been extinguished. It’s a remarkable transformation.

Mosjoukine was a generous co-star and the other stars of the show match him in ability. I rather like Nathalie Lissenko as the leading lady of the picture. Her films career is not extremely well-represented on home media—we mostly have the films she made with Mosjoukine—but, as is the case with many actresses who do not fit the Hollywood stereotype, there are obnoxious creeps who whine about her not being young or pretty enough. Lissenko, you see, committed the unforgiveable crime of being a woman over forty with a film career.

First of all, I would like these twerps to submit photos of their faces for examination and they had better be gorgeous. Lissenko was more handsome than beautiful but this gives her acting gravity and opens up roles that would be over the heads of the more conventional Kewpie doll starlets. There is a very good reason why Lissenko was cast as Elena and Mary Odette as Anna and not the other way around.

Second, it is true that Lissenko was five years Mosjoukine’s senior but it works well for the role of the worldly countess. This woman has seen everything but she has still allowed herself to buy into the Kean mystique and Lissenko plays the part beautifully. In any case, Mosjoukine obviously found her attractive in real life because he married her.

(I should very much like to know if people whining about the age difference between Lissenko and Mosjoukine had similar reservations about the very young leading ladies of John Barrymore, Douglas Fairbanks or Richard Barthelmess. I am also very curious about their opinion of The Son of the Sheik, in which Rudolph Valentino was five AND A HALF years older than Vilma Banky.)

The point of all this? Lissenko is good and I like her, so there. (Sticks out tongue at computer screen.)

What about the other stars? Well, as he did in House of Mystery, Nicolas Koline manages a bit of scene-stealing as the long-suffering Salomon, a character who can only stand back and watch as his close friend destroys himself. Mary Odette does well enough, though her character is probably the weakest in the film. She is essentially there to be Ophelia-ish and beautiful in a youthful kind of way. Otto Detlefsen is suitably dissolute and arrogant as the Prince Regent.

Kean is made very much in the European style. It takes its sweet time but a slower pace does not mean a dull film. Everything that is established in the first act is used again throughout the film, sometimes in unexpected ways. And, like so many of the Volkoff-Mosjoukine productions, it has a way of grabbing you by the throat and refusing to let go. Its story is absorbing; you have to know what happens next.

While The Burning Crucible is insane, The House of Mystery is an addictive crowd-pleaser and Michael Strogoff has action galore, Kean most reflects the sort of lavish French productions that made Mosjoukine’s reputation in Europe. Gorgeous costumes, bold editing, imaginative direction and assertive acting blend together in a production that says “QUALITY” in every frame. Viewers need to know what they are getting into and I would not necessarily choose it as an introduction to Mosjoukine’s talents but it is a brilliant film that rewards astute viewers and repeated viewings. In fact, re-watches are almost essential to understand all the layers of this picture.

Movies Silently’s Score: ★★★

Where can I see it?

Kean has been released on DVD by Flicker Alley as part of their Russian Emigres in Paris box set. (The set is a must-buy for anyone even slightly interested in film history, by the way. I consider it a core part of any classic movie library.) Flicker Alley has also made Kean available for digital rental on their Vimeo channel (it works like any other online digital rental service). As of this writing, the price is $2.95 for a 30 day rental period if you just rent Kean or $5.95 for a 30 day rental of all five films in the Emigres box set, including Kean. Many online movie rentals last 24 hours to 7 days, so the 30 rental period is quite generous.

Flicker Alley’s release features a gorgeously restored print and an excellent orchestral score from Robert Israel. Israel uses suitable classical pieces to recreate the Regency period in musical form and the score adds considerably to the experience.

Thanks for this review. It is even more interesting to read if one has seen the movie.

Since you mentioned that Mosjoukine married Lissenko – I am not sure about this. Neither French nor Russian biographers of Mosjoukine mention of a marriage between the two of them. There is no trace of a divorce as well. And there must have been one if Mosjoukine had been married to Lissenko since he married a young Danish actress in 1928. This union had been covered by French magazines at least.

Without doubt Lissenko and Mosjoukine were a pair from the late 1910s until well into the 20s but seem never to have tied the knot.

Please correct me if I should be wrong.

You bring up a fascinating mystery! Multiple sources in English, French and German publications refer to Lissenko as Mosjoukine’s wife but on closer examination, the earliest one is from the 1950s when many of the Albotros personnel were dead or forgotten. This deserves investigation. So little is known about Mosjoukine, as we both know, and records of the marriage, if it happened, would likely be in Russia, if they exist at all.

I will provide links to my sources for the marriage (all post-1950) later. I’m on the road now but will get back to my computer later today.

Ok, I’m back with the sources, as promised:

This is from 1969 and refers to Lissenko as Mosjoukine’s wife but, of course, this was 30 years after his death

https://books.google.com/books?id=oU0bAQAAIAAJ

This is from 1983:

https://books.google.com/books?id=-l9ZAAAAMAAJ

Both the Russian film databases list Mosjoukine as a spouse but they do not cite a contemporary source:

http://www.kinopoisk.ru/name/371047/

http://www.kino-teatr.ru/kino/acter/w/sov/32153/bio/

As I stated before, none of these sources were created within Mosjoukine’s lifetime so take them for what they are.

Three possibilities:

1. Lissenko and Mosjoukine were married in Russia and the records are lost

2. They were not married but may have said they were to more conservative people as a polite social lie

3. They were never married and the misconception arose because of a mistranslated phrase or some other misunderstanding.

Of course, this doesn’t alter the main point that they definitely found one another attractive in real life. 😉

Kean is a great film. The more extreme acting really fits the nature of the story and its themes too. I cannot thank you enough for introducing us to these little-known treasures and players in film history; Mosjoukine is just fabulous, now officially one of my faves.

Yay! Welcome to the club! Here is your official badge and pot of caviar. 😉

Quite an interesting review of a film I now must see and is sitting idly on a shelf in my house. I won’t complain about spoilers since I didn’t have to read them and seem irrelevant to my enjoyment of the film, unlike, say, knowing too much about House of Mystery the first time.

You’re comments about biopics are spot on: any film which consists of the greatest hits in someone’s life in chronological order induces in me a state of catatonic boredom, whether it be “nonfiction”, e.g., Wilson, or not, e.g., Driving Miss Daisy.

Thanks! I don’t really consider it a spoiler when the film is based on a fairly famous person. It’s not a spoiler, for example, to say that a biopic of Jayne Mansfield ends with her dying in a car accident.

Yeah, biopics absolutely drive me nuts unless they are very carefully handled. I much prefer a central, driving storyline that covers a shorter period.

Terrific review! I did not know that this film predated Battleship Potemkin with the series of fast edits.

Yes and Mosjoukine’s THE BURNING CRUCIBLE is even earlier. The Russian emigres really deserve credit for a lot of modern filmmaking techniques.

Yes, I agree re: biopics – Take the most interesting year/few years of a person’s life and focus on that, instead of trying to cram their whole life story into 2 hours. The French film, Coco Before Chanel, did a lovely job focusing on Chanel in the few years before she hit The Big Time.

Terrific review, Fritzi! I laughed out loud at the thought of you fainting on a brocade couch because the film changed some of the actual events. Great stuff!

Thank you! Yes, the traditional biopic really needs to be shown the door.

France was definitely ground zero for fast-cutting/montage techniques. The Russian émigrés deserve credit here, but I think it was Abel Gance’s game first.

I enjoyed reading your review. I actually wasn’t too big a fan of Kean … as much as I love Mosjoukine, I found this film lacking something. Koline was the heart of the film for me – great performance.

Yes, I believe “La roue” is often cited as the inspiration for bolder editing, though if viewing silent films has taught me anything, it’s that “first” should almost always be led by “one of the” But the émigrés definitely deserve credit for early adoption.

This film sounds interesting. The Salomon-Kean dynamic looks like what I would enjoy most, but I’m sure I’d like the Kean breakdown scenes too!

It’s a pretty interesting ride 🙂

I don’t like it much of the time when they take a perfectly interesting life and change up the story. Kean sounds interesting. Haven’t seen it though.

Arlee Bird

Tossing It Out

I think, like everything else in life, balance is called for. Real human lives are messy. There are too many characters, foreshadowed events never transpire and very little gets wrapped up in neat bows. Movies (or, in this case, playwrights like Dumas) need to tidy things up, slim down the story and find the narrative thread. Of course, they can go too far.

I didn’t give this movie enough of a chance. I thought our Ivan was simply overwrought. Thank you for clearing my head. I’ll watch it again.

Yay! 🙂