Welcome to the fourth and final article on my series on silent movie research. Part one dealt with fibbing film stars, part two discussed the responsibilities of film historians, part three covered the problems caused by bloggers and the wiki culture. This time, we are going to be discussing something of a sticky topic: Using research or testimony that you know is questionable.

Why would anyone do that? Well, silent movies are not exactly a happening thing. With more obscure stars and films, imperfect sources may be all we have. It’s a question of using a fishy source gingerly or having no source at all. There is a time and a place for either option.

Step one: Acknowledge, acknowledge, acknowledge

If you have any reason to doubt the veracity of your source, state this in your writing. Has your source made unfounded claims? Have they been caught in lies? You owe it to your readers to acknowledge this and state why you believe the source this time.

So far so good. But what about specific instances?

Wonderful, horrible fan magazines

Fan magazines were a mixture of gossip, fantasy, studio stunts and a few grains of truth. Sometimes you can learn a lot from what they don’t say. For example, if a star was on every page one month and then gone the next, there is a good chance that they were embroiled in scandal or dropped from their studio contract. The time of the drop gives you a clue for tracking down further information.

Fan magazine writers could be petty, sexist, racist and generally unpleasant and cruel. If you run into a really mean quote, you may do well to track down information on the writer. (Adela Rogers St. John has made my blacklist with her petty swipes.)

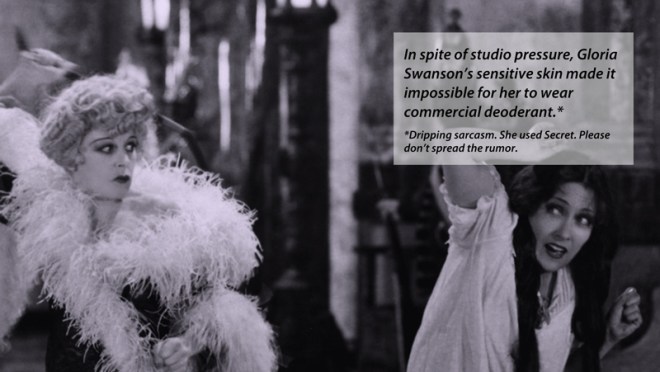

And fan magazines were not above holding grudges. For example, Photoplay reportedly took an intense dislike to Lillian Gish in the twenties because she politely refused to have her likeness engraved on Photoplay commemorative spoons. Yes, really. I imagine she reacted to the suggestion somewhat like this:

From that point on, Gish was labeled snobby, frumpy, sexless and her performances were ignored or played down. While there is no smoking gun (for example, a “get Gish” telegram) in the case, it definitely has the ring of truth to me.

Charles Affron recounts the episode in his biography Lillian Gish: Her Legend, Her Life. The book has lots of interesting details and mythbusting but the author seems to have taken a dislike to his subject. In this case, though, Affron is sympathetic to Miss Gish. Who wouldn’t be? “Take part in our tacky spoon peddling– or else.”

Unfortunately, for more obscure stars, the fan magazines are pretty much all we have. Just assume that they are least 75% baloney. When quoting a fan magazine for a more controversial claim that is not backed by any other source, it is probably best to briefly acknowledge the credibility issues.

Slips of the tongue

When dealing with a recorded interview, slips of the tongue are inevitable. With written reviews, memories can be hazy and there may be a few mix-ups. For example, you may wish to quote an actor who verbally mixes up Constance and Norma Talmadge. Everything else he says seems to check out, there was just that one slip of the tongue.

So, the original quote looks like this:

“It was such a pleasure working with Constance Talmadge. You really should see her in Kiki.”

There is a right way and a wrong way to handle it.

The wrong way:

“I was such a pleasure working with Norma Talmadge. You should really see her in Kiki.”

What’s wrong? Well, in this case, we corrected the original speaker’s quote but we did not tell the reader that we were doing so. This is highly misleading (even if well-intended) and is irresponsible writing. Whoopsy!

The right way:

“It was such a pleasure working with Constance Talmadge. You really should see her in Kiki.”

Note: It seems clear from context that Thomas Actor was referring to Norma Talmadge, Constance’s sister.

If you need to use the quote, do not correct it or change it in any way. You may add clarifying notes but anything more would not be the ticket. The same goes for paraphrasing.

If you only have one quote on the topic and there is an obvious slip of the tongue, you need to acknowledge it. It’s only fair. After all, not everyone may agree that it is a slip of the tongue. And, obviously, deciding whether or not something is a slip of the tongue is a judgement call on the part of the writer.

Judgment calls and lifting your fingers

In fact, writing about history of any kind is a series of judgement calls. I cannot emphasize enough the importance of looking at the big picture. Many movie myths can be debunked by something as simple as looking a movie release dates to see if they match the testimony given. It also helps to read history books about the era that are not related to film. Many times, myths and errors get repeated and accepted as fact because no one has ever bothered to lift a finger and do even a minimum amount of research.

For example, there is a common myth that Russian leading man Ivan Mosjoukine was invited to Hollywood as a Valentino replacement after the famous leading man’s sudden death. The story goes that studio heads saw an opportunity to inherit Valentino’s box office appeal and scoured far and wide for a new sheik. Supposedly, the search led Carl Laemmle to Mosjoukine’s work in France, which led to an invitation to Universal.

All it took to debunk the myth was a few hours of digging through back issues of trade journals to discover this was not the case at all.

This is dated August 14, 1926. Valentino died unexpectedly on August 23. Case rested.

(You can read the full, crazy account of my Mosjoukine mission in my review for Surrender, his lone Hollywood appearance.)

So, look for context. Many times, the answer that you need is just beneath the surface. Be the one who lifts a finger and corrects the historical record.

Well, that book is riddled with errors. Let’s use it as a source.

Here is a pop quiz for all you junior film historians. Let’s say you run into a book with juicy claims about a famous person. But, oh dear, it seems that it has some basic factual errors. Dates are wrong. Names are wrong. People are said to be places where they couldn’t possibly be (and photographs prove it). But the claims are so… juicy!

What do you do?

a) Use the claims as-is. No one will notice!

b) Quietly correct the factual errors but use the claims in your juicy article.

c) Do further research before using the juicy claims. If you do use the source, mention its credibility issues.

Obviously, C is the best choice but you would be amazed at how many folks take the A and B path. Obviously, I have a few issues with this.

For example, in researching my epic (she said modestly) debunking of the perfectly silly “Woodrow Wilson murdered Florence La Badie” myth, I read as much as I could find. For those of you who missed the drama, the claims are found in exactly one book: Stardust and Shadows: Canadians in Early Hollywood by Charles Foster. The book gets birthdates wrong, misnames La Badie’s mother, quotes people who could not possibly have witnessed the events in question, gives only vague dates for newspaper articles (none of which seem to exist) and generally raises red flags all over the place.

The problem was that many of writers who repeated the affair/murder narrative chose option B. That is, they took the errors in the original source and corrected them (birthdates, names, etc.), did not mention that they had made corrections and unquestioningly recited everything else. Oh dear.

You see the problem? I hope so. It gives false credibility to the original source but does not question its allegations, which are pretty fishy. In short, it makes the “scandal” look a lot more believable than it really is. I dare say that many of these people meant well but the result is playing havoc with the historical record and causing confusion where there should be none.

That’s not a nice thing to do.

Again, I am not a huge fan of bashing fellow film bloggers but these murder claims are smearing a lot of very good people and they must surely cause distress to the descendants of the wrongly accused. Please think before you type! These people have families. How would you like to have your grandparents written about in this way?

(Mercifully, the rumor has not spread too far yet and Wikipedia is, as of the writing, actively deleting mentions of this nonsense from their Florence La Badie page.)

Look at yourself

Here come the questions that only you can answer. Why are you doing this? Why do you want to write about this star, this director, this film? You don’t need a complicated reason. Maybe you just like them. But please be aware that liking a person’s work can color what information you choose to include or exclude.

(I think every single one of us has been guilty of this.)

Taking a balanced approach is difficult but worth your time and effort. Does this mean you can’t have opinions? Of course not! It just means that responsible writers acknowledge their likes and dislikes and realize how it can color their writing.

For example, the more I learn about D.W. Griffith and watch his films, the more I grow to detest the man and his feature work. Some silent film fans feel he is unfairly maligned and want to restore his reputation. I respectfully disagree. I want to tie cinder blocks to his reputation and toss it into the Mariana Trench. What does this mean? Well, it means that his fans are more likely to believe positive accounts of Griffith and I am more likely to believe negative accounts. Again, nothing wrong with having an opinion. Just know that it will make a difference with your baloney detectors.

Silent movie fans are a small but dedicated group. Because there are so few of us, it means that those who choose to write about the topic have an enormous responsibility. Yours may be the only voice discussing a particular star or film. Please, for the sake of the historical record, do your very best to get it right.

Thank you so much for this article. Great information.

Glad you enjoyed it!

Well done work here, Fritzi!

Thanks! 🙂

Don’t hold back about Griffith! Tell us how you really feel!

😉

Very much in agreement with these points, Fritzi (as you would guess!). Being one of those oh-so-normal people who delight in doing hardcore research on the silent era, one tip of mine is to get to know the various film magazines. There’s plenty of marshmallow fluff for the fans like “Film Fun” (I swear these get fluffier the closer they get to the ’30s) but there’s also practical, informative publications like “Exhibitor’s Trade Review.” Fluff can be useful if viewed objectively; it can tell us how stars were marketed and how certain stars were regarded by writers (like the example you gave with Lillian Gish). But of course you need to read, read, read as many sources as possible. The more you read, the easier it will be spot which stories are probably phony and which ones probably have some truth to them.

But I will say one thing: even the goofiest of fan magazines are stuffed with priceless photos.

Yes indeed. The trade periodicals definitely cut the fluff. It’s all about which movies will pack the houses and which seem a little weak. Thanks for the additional tip. 🙂